Counterspace capabilities

Kinetic space weapons

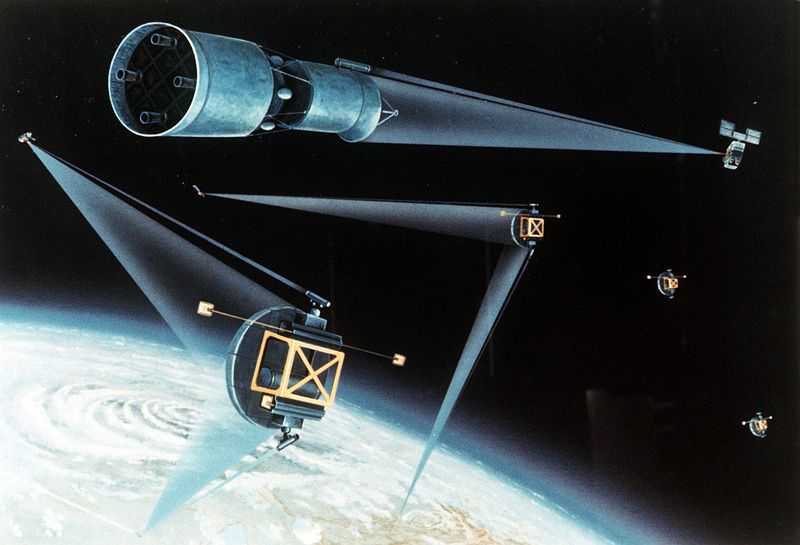

Kinetic space weapons destroy satellites by a kinetic impact (or eventually by nearby detonation). They comprise direct ascent kinetic anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons, co-orbital anti-satellite weapons or traditional terrestrial attacks on space ground segments. Kinetic attacks result in the irreversible destruction of space systems and, in space, create hazardous space debris that endangers other systems and thus limits their practical utility despite their effective destructive potential. As of August 2023, direct ascent kinetic anti-satellite weapons had been successfully tested by four nations – the United States, China, India and Russia.

The United States first successfully tested a direct ascent kinetic anti-satellite weapon in 1985 by using ASM-135 ASAT launched from an F-15 fighter to destroy the obsolete Solwind P78-1 satellite. It then reconfirmed its anti-satellite capability in 2008 by using an SM-3 missile from the Aegis ballistic missile defence system to destroy the USA-193 satellite. In 2007, China tested a modified DF-21 ballistic missile (dubbed SC-19) to destroy the Fengyun-1C satellite. Targeting Microsat-R, India tested the modified ballistic missile interceptor Prithvi Defence Vehicle Mark-II in 2019. Lastly, in 2021, Russia conducted a direct ascent kinetic anti-satellite test with the anti-ballistic missile Nudol PL-19 by intercepting the Cosmos 1408 satellite. The tests conducted, especially by China and Russia, are deemed highly irresponsible due to the large amount of debris created. High-altitude debris clouds can orbit for decades, and Chinese and Russian anti-satellite tests even endangered the inhabitants of the International Space Station.

Beyond this, the United States is also capable of advanced orbital rendezvous and proximity operations in both low Earth orbit and geostationary orbit that could lead to the development of co-orbital anti-satellite weapons within a short period of time. China has proven similar capabilities, and Russia already tested co-orbital satellite weapons during the Cold War and, since 2010, has renewed those capabilities.

Directed energy space weapons

Directed energy (or non-kinetic physical) space weapons include low and high-power lasers, high-powered microwaves (HPM) and electromagnetic pulse (EMP).

Low-power lasers can ‘blind’ or ‘dazzle’ enemy satellites. Dazzling refers to temporary loss of sight of the satellite, and blinding causes permanent damage to satellite optics. High-power lasers thus permanently damage other satellite electronics. High-powered microwaves disrupt satellite electronics, corrupt data stored in memory, cause processors to restart, and, at higher power levels, cause permanent damage to electrical circuits and processors. Electromagnetic pulse is created by nuclear explosions and can damage satellite electronics in a large radius. Directed energy attacks operate at the speed of light and, in some cases, are difficult to attribute.

The major space powers – the United States, Russia and China – are engaged in developing directed energy space weapons and can probably dazzle or blind low Earth orbit satellites. Moreover, France is developing ground-based and space-based lasers with offensive capabilities with the aim of them being operational by 2030.

Electronic space weapons

Electronic space weapons interfere with the electromagnetic spectrum through which space systems transmit and receive data. Electronic attacks include satellite jamming, spoofing and meaconing. Jamming attacks emit noise in the same radio frequency (RF) as the satellite and within the field of view of its antennas. Uplink jamming interferes with the signal from Earth to space, while downlink jamming targets the signal coming from space to Earth. Spoofing is a method of sending fake signals or commands to the receiver. Meaconing refers to a particular type of spoofing that only re-transmits the original signal copy and thus does not require breaking the encryption. Electronic attack, for instance, interferes with GPS signals and communications satellites or sends false locations to the receiver.

Electronic warfare capabilities are relatively cheap and sometimes commercially available. Therefore, all major space powers have advanced electronic warfare capabilities that can be utilised as space weapons.

Cyberspace weapons

Compared to other space weapons, cyberattacks are inexpensive, flexible and generally reversible methods of disruption which are difficult to attribute. The impact of cyberattacks ranges from data loss to widespread disruptions or permanent loss of a satellite. Despite sometimes requiring advanced technical knowledge, due to their cost-effectiveness and availability, cyberattacks are employed by states, but also private groups or individuals. For instance, in 2007 and 2008, China allegedly interfered with two US government satellites. In 2009, Iraqi insurgents used cheap SkyGrabber software to hack US military Predator drones. Between 2008 and 2016, the Russian-led Turla group accessed sensitive data from Western embassies, governments and military institutions.

There are plenty of more recent examples as well. Following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia launched cyberattacks on Viasat and SpaceX space companies, which also revealed further gaps in cyber protection. While SpaceX’s Starlink proved to be resistant to the Russian cyberattacks, Viasat allegedly downplayed the cyber threat that led to disruptions in Ukraine and throughout Europe.

Space hybrid operations

Space hybrid operations are defined as ‘intentional, temporary, mostly reversible, and often harmful space actions/activities specifically designed to exploit the links to other domains and conducted just below the threshold of requiring meaningful military or political retaliatory responses’2. They comprise (1) directed energy operations; (2) orbital operations; (3) electronic operations; (4) cyber operations; and (5) economic and financial (E&F) operations.3 Space hybrid operations are characterised by ambiguous attribution, and temporary and reversible effects, and are generally not publicly visible.4 Accordingly, space hybrid operations are a convenient method of undermining an adversary’s capabilities while limiting space debris proliferation and, in comparison to kinetic and other destructive methods, are relatively considerate to the space environment.5

Illustrations of deployable space hybrid operations (Robinson et al., 2018, p. 3)

| SPACE HYBRID OPERATION6 | EXAMPLES | ATTRIBUTION | REVERSIBILITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directed energy operations that may result in space debris7 | Low-power laser dazzling or blinding;8 high-power microwave (HPM) or ultra-wideband (UWB) emitters | Varies | Generally reversible |

| Orbital operations that generally do not result in space debris | Space object tracking and identification; rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO) | Varies | Fully reversible |

| Electronic operations9 | Jamming10 (orbital/uplink, terrestrial/downlink); spoofing11 | Moderate | Fully reversible |

| Cyber operations12 | Attack on satellite or ground station antennas; attack on ground stations connected to terrestrial networks; attack on user terminals that connect to satellites | Difficult | Generally reversible |

| Economic and financial (E&F) operations13 | Investments in target country’s space infrastructure for purpose of influence/control; provision of loans and construction/launch of target country’s space system(s) | Varies | Generally reversible |

Nevertheless, space hybrid interference can be measured, similarly to cyberattacks, via the ‘effects-based doctrine’. This means that the qualification of the attack is assessed in light of the consequences and damage caused. If a particular space hybrid disruption causes substantial harm and damage, the quantity and quality of which is equivalent to the destruction produced by a conventional armed attack (e.g. deactivation of data/signals paralysing the functioning of the critical infrastructure of the state, causing significant damage or even fatalities), the qualification of ‘armed attack’ might apply.14

Space hybrid operations are conducted in the ‘grey zone’ below the threshold of conflict. That said, space hybrid operations reside in harmful/offensive capabilities that can be employed during space warfare, potentially accompanied by, for instance, kinetic anti-satellite weapons.

Dual-use nature of space technology

In the context of dual-use technologies, on-orbit servicing (OOS) refers to the capability to repair, maintain, upgrade or refuel satellites, spacecraft or other assets while they are in space and it can have both civilian and military applications.19

Civilian applications of OOS include extending the operational life of satellites by refuelling them or replacing faulty components, thus reducing the need for costly replacements and contributing to sustainability in space. It can also enable the deployment of larger and more complex space structures by assembling them in orbit from smaller components that have been launched separately.

On the military side, OOS can support national security objectives by allowing for the maintenance and upgrade of military satellites, enhancing their resilience and responsiveness. It can also facilitate the deployment of reconnaissance, surveillance and communication capabilities in space, supporting military operations and strategic goals.

Active debris removal (ADR) refers to the process of actively retrieving defunct or non-functioning satellites, rocket stages and other space debris from the Earth’s orbit. In the context of dual-use technologies, ADR involves the utilising technologies that have both civilian and military applications.20

On the civilian side, ADR is primarily aimed at mitigating the growing problem of space debris, which poses a significant risk to operational satellites and spacecraft. As more objects are launched into space, the amount of debris increases, raising concerns about collisions and the generation of even more debris in a cascading effect known as the Kessler syndrome.21 Active debris removal technologies are crucial for maintaining the long-term sustainability of space activities by reducing the risk of collisions and ensuring the safety of critical space assets.

From a military perspective, ADR technologies can also be viewed as dual use because they have potential applications for enhancing national security. Military satellites and spacecraft are equally vulnerable to collisions with space debris, which could disrupt communications, surveillance and navigation systems. By developing and deploying ADR capabilities, military forces can protect their space assets and maintain their strategic advantage in space operations.22

Conclusion

Space hybrid operations, defined as deliberate, mostly reversible activities in space, conducted strategically below the threshold that would necessitate significant military or political retaliation, and space weapons, categorised into kinetic, directed energy, electronic and cyber types, pose complex challenges due to their dual-use nature. While kinetic weapons cause irreversible satellite damage and create hazardous space debris, directed energy technologies disrupt or damage satellites through lasers and microwaves. Electronic warfare, involving jamming and spoofing, interferes with space signals, and cost-effective and flexible cyberattacks pose significant threats to space assets. The dual-use nature of space tech demands stringent governance and international cooperation to ensure responsible and sustainable space utilisation

Quiz

Sources for this chapter

Alver, James, Andrew Garza, and Christopher May. “An Analysis of the Potential Misuse of Active Debris Removal, On-Orbit Servicing, and Rendezvous & Proximity Operations Technologies”. The George Washington University, Washington, D.C., 2019.

Bingen, Kari A./Johnson, Kaitlyn/Young, Makena/Raymond, John. 2023. “Space Threat Assessment 2023”. CSIS, available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/space-threat-assessment-2023.

Cohen, Rachel S. “Spacecom Calls out Apparent Russian Space Weapon Test”. Air & Space Forces Magazine, 24 July 2020, available at: https://www.airandspaceforces.com/spacecom-calls-out-apparent-russian-space-weapon-test/.

DLR. On-orbit servicing technologies, 1 February 2022, available at: https://www.dlr.de/rb/PortalData/38/Resources/dokumente/leistungen/DLR_RB_Portfolio_OOS.pdf.

Doboš, Bohumil/Pražák, Jakub. 2019. “To Clear or to Eliminate? Active Debris Removal Systems as Antisatellite Weapons”. Space Policy 47: 217–23, available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2019.01.007.

ESA. Active debris removal, 1 January 2024, available at: https://www.esa.int/Space_Safety/Space_Debris/Active_debris_removal.

Johnson-Freese, Joan. 2007. Space as a strategic asset. New York: Columbia University Press.

Manson, Katrina. 2023. “The Satellite Hack Everyone Is Finally Talking About”. Bloomberg, available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2023-russia-viasat-hack-ukraine/.

McConnaughey, Paul K./Femminineo, Mark G./Koelfgen, Syri J./Lepsch, Roger A./Ryan, Richard M./ Taylor, Steven A. 2012. “NASA’s Launch Propulsion Systems Technology Roadmap”. NASA, Office of the Chief Technologist, available at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20120014957/downloads/20120014957.pdf.

Ministère des Armées. 2023. “LPM 2024-2030: Les Grandes Orientations”. https://satelliteobservation.net/, available at: https://satelliteobservation.files.wordpress.com/2023/04/livret-de-presentation-de-la-loi-de-programmation-militaire-2024-2030-6-avril-2023.pdf.

Mistry, Dinshaw/Gopalaswamy, Bharath. 2012. “Ballistic Missiles and Space Launch Vehicles in Regional Powers”. Astropolitics 10 (2): 126–51, available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14777622.2012.696014.

Mowthorpe, Matthew/Trichas, Markos. “A Review of Chinese Counterspace Activities”. The Space Review: A review of Chinese counterspace activities, 1 August 2022, available at: https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4431/1.

Peck, Michael. 2023. “Russia’s Electronic Warriors Are Intercepting Ukrainian Troops’ Communications and Jamming Their GPS-Guided Bombs, Experts Say”. Business Insider, available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/russian-electronic-warfare-interfering-with-ukrainian-radios-bombs-2023-7.

Pražák, Jakub. 2021. “Dual-Use Conundrum: Towards the Weaponization of Outer Space?” Acta Astronautica 187: 397–405, available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2020.12.051.

Pražák, Jakub. 2022. “On the Threshold of Space Warfare”. Astropolitics 20 (2–3): 175–91, available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14777622.2022.2142351.

Pražák, Jakub. 2021. “Space Cyber Threats and Need for Enhanced Resilience of Space Assets”. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Warfare and Security, available at: https://doi.org/10.34190/ews.21.006.

Rashid, Fahmida Y. 2011. “Chinese Military Hackers Blamed for Attacking Two U.S. Satellites”. eWEEK, available at: https://www.eweek.com/security/chinese-military-hackers-blamed-for-attacking-two-u.s.-satellites/.

Robinson, Jana/Šmuclerová, Martina/Degl’Innocenti, Lapo/Perrichon, Lisa/ Pražák, Jakub. 2018. Europe’s Preparedness to Respond to Space Hybrid Operations. Prague Security Studies Institute Report, available at:https://www.pssi.cz/download//docs/8252_597-europe-s-preparedness-to-respond-to-space-hybrid-operations.pdf.

Smeltzer, Stanley/Wagner, Nathan. 2022. “De-Orbit Analysis using Active Debris Removal for High Priority Objects”. In: ASCEND 2022, p. 4,275.

United States Department of Defense. “Joint Publication 3-14: Space Operations”. www.jcs.mil, 2020, available at: https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_14Ch1.pdf.

Velkovsky, Pavel/Mohan, Janani/Simon, Maxwell. “Satellite Jamming”. On the Radar, 3 April 2019, available at: https://ontheradar.csis.org/issue-briefs/satellite-jamming/#fn:1.

Weeden, Brian/Samson, Victoria. 2023. Global Counterspace Capabilities Report, available at: https://swfound.org/counterspace/

Footnotes

-

Weeden, Brian/Samson, Victoria. 2023. Global Counterspace Capabilities Report, p. xvi, available at: https://swfound.org/counterspace/. ↩

-

Robinson, Jana/Šmuclerová, Martina/Degl’Innocenti, Lapo/Perrichon, Lisa/Pražák, Jakub. 2018. Report. Europe’s Preparedness to Respond to Space Hybrid Operations. Prague Security Studies Institute, p. 3, available at: https://www.pssi.cz/download//docs/8252_597-europe-s-preparedness-to-respond-to-space-hybrid-operations.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Robinson, Jana/Šmuclerová, Martina/Degl’Innocenti, Lapo/Perrichon, Lisa/Pražák, Jakub. 2018. Report. Europe’s Preparedness to Respond to Space Hybrid Operations. Prague Security Studies Institute, p. 4, available at: https://www.pssi.cz/download//docs/8252_597-europe-s-preparedness-to-respond-to-space-hybrid-operations.pdf. ↩

-

Pražák, Jakub. 2022. “On the Threshold of Space Warfare”. Astropolitics 20 (2–3): 175–91, available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14777622.2022.2142351. ↩

-

This list purposely does not include ground-based kinetic ASAT weapons, co-orbital kinetic weapons, electromagnetic pulse (EMP) weapons, high-power lasers etc. as their effects are easier to attribute and are not reversible. ↩

-

The attack is swift and degradation of the target spacecraft may not be immediately apparent. ↩

-

Spoofs or jams of satellite electro-optical sensors using laser radiation that is in the sensor pass band (in-band), temporarily blinding the satellite. ↩

-

The use of electromagnetic or directed energy to control the electromagnetic spectrum or to attack an adversary’s space system. Communications/navigation satellites and other satellite’s communications, data and command links are likely targets. ↩

-

Emitting noise or some other signal for the purpose of preventing the sensor from being able to collect the real signals. ↩

-

Emitting false signals that mimic real signals to cover the real signals (a type of electronic decoy). ↩

-

Targets data and the systems that use that data (i.e. information services and operator’s control over the asset). ↩

-

Use of economic and financial transactions to advance ‘space sector capture’ (PSSI defines space sector capture as ‘a state actor’s provision of space-related equipment, technology, services and financing ultimately designed to limit the freedom of action and independence of the recipient state’s space sector, generally implemented on an incremental basis’). ↩

-

Robinson, Jana/Šmuclerová, Martina/Degl’Innocenti, Lapo/Perrichon, Lisa/Pražák, Jakub. 2018. Report. Europe’s Preparedness to Respond to Space Hybrid Operations. Prague Security Studies Institute, p. 18, available at: https://www.pssi.cz/download//docs/8252_597-europe-s-preparedness-to-respond-to-space-hybrid-operations.pdf. ↩

-

Johnson-Freese, Joan. 2007. Space as a Strategic Asset. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 28. ↩

-

Doboš, Bohumil/ Pražák, Jakub. 2019. “To Clear or to Eliminate? Active Debris Removal Systems as Antisatellite Weapons”. Space Policy 47: 217–23, available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2019.01.007. ↩

-

Cohen, Rachel S. “Spacecom Calls out Apparent Russian Space Weapon Test”. Air & Space Forces Magazine, 24 July 2020, available at: https://www.airandspaceforces.com/spacecom-calls-out-apparent-russian-space-weapon-test/. ↩

-

Mowthorpe, Matthew/Trichas, Markos. “A Review of Chinese Counterspace Activities”. The Space Review: A review of Chinese counterspace activities, 1 August 2022, available at: https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4431/1. ↩

-

DLR. On-orbit servicing technologies, 1 February 2022, available at: https://www.dlr.de/rb/PortalData/38/Resources/dokumente/leistungen/DLR_RB_Portfolio_OOS.pdf. ↩

-

ESA. Active debris removal, 1 January 2024, available at: https://www.esa.int/Space_Safety/Space_Debris/Active_debris_removal. ↩

-

Smeltzer, Stanley/Wagner, Nathan. 2022. “De-Orbit Analysis using Active Debris Removal for High Priority Objects”. In: ASCEND 2022, p. 4,275. ↩

-

Alver, James/Garza, Andrew/May, Christopher. 2019. “An Analysis of the Potential Misuse of Active Debris Removal, On-Orbit Servicing, and Rendezvous & Proximity Operations Technologies”. The George Washington University, Washington, D.C. ↩