Space partnerships have become an operational, political and strategic centrepiece among major global powers. At the same time, the geopolitical environment has deteriorated significantly over the past decade, reflecting the ambition of powers such as China and Russia to assume greater leadership roles regionally and globally. In recent years, this has led to an escalation of conflicting interests and international competition between spacefaring powers, particularly the US and China.

- 2019

Chandrayaan-2 Mission by India

India’s Chandrayaan-2 mission aims to explore the Moon’s south pole and investigate lunar water ice, marking a significant step in lunar exploration.

- 2019

Chang'e-4 Lands on the Far Side of the Moon

China’s Chang’e-4 spacecraft successfully lands on the far side of the Moon, becoming the first mission to achieve this feat.

- 2019

US Establishes Space Force

The United States establishes the Space Force, emphasizing the growing importance of space as a military domain.

- 2020

SpaceX's Crewed Test Flight to ISS

SpaceX conducts the first crewed test private sector flight to the ISS, carrying astronauts aboard the Dragon spacecraft, a historic milestone for commercial space travel.

- 2021

Discussions on Space Regulation

Growing commercial space endeavors intensify discussions about regulating private sector activities in space, highlighting the need for governance frameworks.

- Present

Future Governance of Space Activities

Ongoing debates and initiatives focus on balancing innovation and security, shaping the future governance of space activities.

US-led international partnership: The Artemis Accords

Since the signing of a new Space Policy Directive in December 2017, the Artemis Program has been the flagship project of the United States Space Program.1 It consists of an ambitious series of missions aimed at achieving the goal of returning men and women to the Moon and preparing for the next stage of Mars exploration. Core objectives include crewed lunar landings (Artemis I-III), putting the first extraterrestrial space station into orbit (Lunar Gateway, Artemis IV and beyond) and, in the longer term, establishing a permanent base on the Moon.

Although NASA has taken a leading role in the project, the Artemis Program is, by design, a multinational effort in which NASA works hand in hand with the agencies of Europe (ESA), Canada (CSA) and Japan (JAXA) as historical partners, particularly when it comes to the Gateway, and has announced cooperation with Israel (ISA), Australia (ASA) and India (ISRO). It also relies on close collaboration with private companies, such as SpaceX (Dragon, Falcon, Starship), Lockheed Martin (Orion), Boeing, Northrop Grumman (SLS) and Blue Origin (HLS).2 The programme’s core identity is rooted in fostering space exploration as a shared and common endeavour for humankind, as it brings together the expertise and capabilities of various nations and entities.

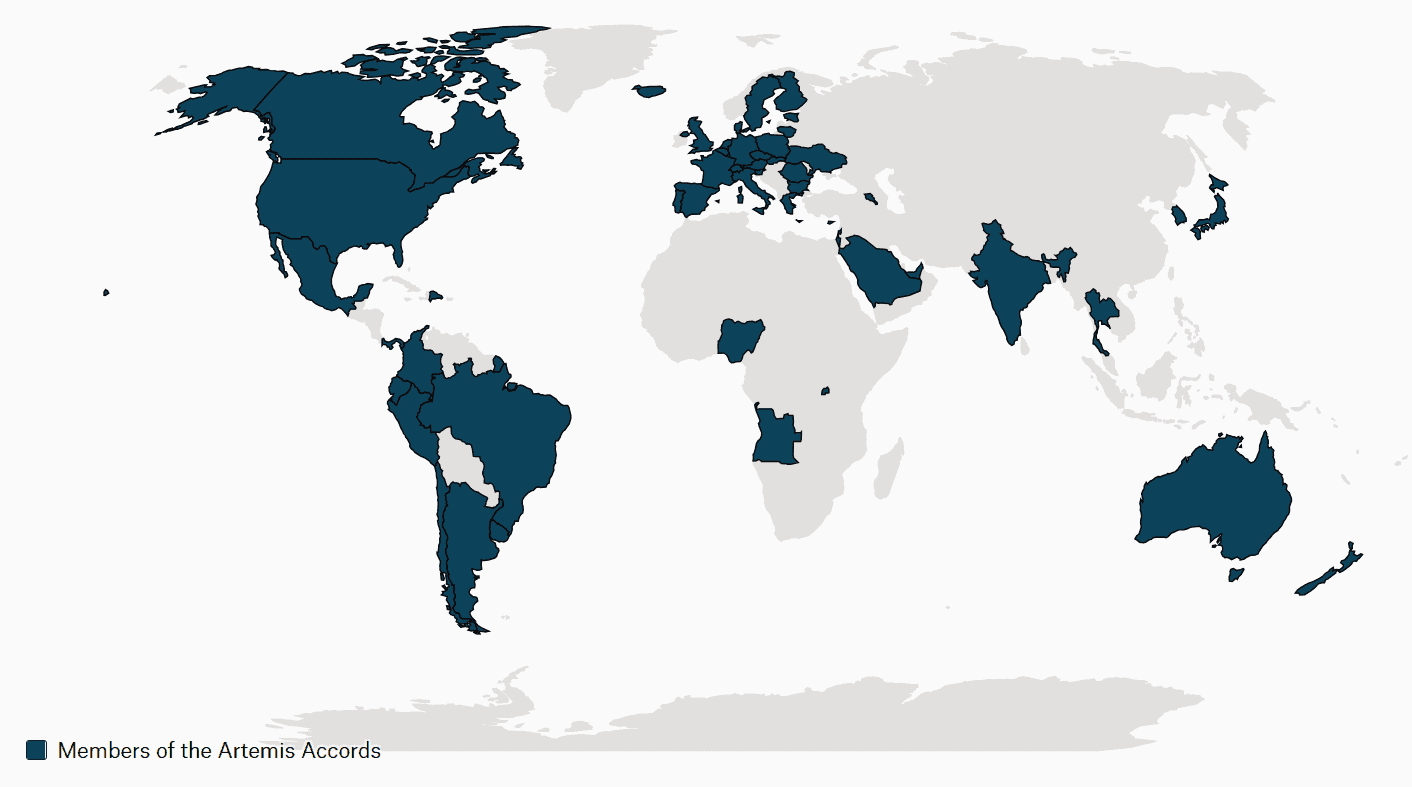

Conjointly with the programme, the US has advanced a body of non-binding arrangements, serving as a prerequisite for participation, called the Artemis Accords.3 They are intended to serve as a comprehensive framework that outlines the principles and procedures for international cooperation in the exploration and exploitation of the Moon and other celestial bodies. The Accords consist of ten core principles derived from the foundational framework established by the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. These are principally designed to guide international partners towards sustainable practices and ensure the responsible and transparent use of outer space for peaceful purposes. The Artemis Accords are a significant multilateral attempt at reinforcing the aging body of space law that has been in existence since the Cold War. By signing the Accords, countries demonstrate their commitment to a democratic, fair and multilateral approach to space exploration. At the time of writing (December 2023), 33 nations are currently party to the Accords4

The Accords have also attracted some criticism. In particular, the clauses regarding the extraction of space resources are based on a limited interpretation of space being ‘not subject to national appropriation’ as outlined by the 1966 Outer Space Treaty.5 The view taken by the Accords is that this only applies to national claims of sovereignty but not to private interests, and would thus allow some forms of space mining for commercial exploitation. This view is debated by legal scholars, although the only openly contradictory interpretation in international law exists in the 1979 Moon Treaty, which has been ratified by only three of the Accords’ current signatories – Australia, the Netherlands and Saudi Arabia.6

Russia and China

Two major spacefaring nations have refused to participate in the collaborative effort spearheaded by the Artemis projects: China and Russia. Both the Chinese (CNSA) and Russian agencies (Roscosmos) have instead announced their own joint international programme, which aims to establish a permanent lunar base by the 2030s, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).7

China has become a particularly fast-rising player, seeking to establish a dominant position in space exploration and resource exploitation with an ambitious space programme. It aims to become a leading space power by 2045 and has promoted its space interests and partnerships via its Space Information Corridor and industrial strategies such as ‘Made in China 2025’ and ‘China Standards 2035’.8 China also pursues civil-military fusion, which is an aggressive national strategy to develop a ‘world-class military’ by 2049.9 However, the authoritarian regime and lack of transparency of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) raise concerns about the intentions behind and potential consequences of these activities. China does not have a history of being very inclusive with its partners when it comes to its programme and has been repeatedly accused of industrial espionage and intellectual property theft.10 In light of this, in 2011, the U.S. Congress banned NASA from cooperating with CNSA, notably preventing China from contributing to the ISS.11 As a result, China launched its own space station (Tiangong), which became fully operational in 2021.

In contrast to China, Russia’s role in space is gradually declining and benefits mostly from the legacy of the Soviet Union. While it still collaborates with Western partners on the ISS, Russia has increasingly emphasised unilateral geostrategic and economic interests in the space domain and beyond, as seen in its 2021 National Security Strategy.12 Although it still possesses significant launch and satellite-building capabilities, Russia’s space programme, in particular after the 2014 and 2022 aggression against Ukraine, has suffered from losing access to Western technologies and is becoming increasingly dependent on players such as China as suppliers of materials and innovation.13

One substantial part of China’s and Russia’s strategic initiatives in space is the building of space infrastructure and the proliferation of related technologies, equipment and services to other countries. This is often done against internationally negotiated norms and by means of heavily subsidised pricing, which creates unfair competition for the rest of the world. Their partnerships also create problematic economic and political dependencies, and fail to foster the sustainable development of the space sector in the recipient countries by obviating the need for indigenous capabilities and expertise.14

Conclusion

In the modern space race, global powers such as the US, China and Russia compete fiercely for space dominance. The US leads with the Artemis Program, involving multiple nations and private companies, while China is rapidly advancing its space programme, with its eye on global leadership. Russia’s space influence is waning, as it faces challenges due to geopolitical tensions and reliance on China. Amidst this competition, concerns arise about fairness and transparency in global space partnerships. As nations vie for supremacy, the race for space not only drives technological advancements but also shapes global power dynamics and ethical considerations

Quiz

Sources for this chapter

China National Space Administration. “JOINT STATEMENT Between CNSA And ROSCOSMOS Regarding Cooperation for the Construction of the International Lunar Research Station”. 29 April 2021, available at: https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/english/n6465668/n6465670/c6811967/content.html.

Cooper, Julian. 2021. “Russia’s updated National Security Strategy”. Russian Studies Series 2/21, available at: https://www.ndc.nato.int/research/research.php?icode=704#_edn1.

NASA. “Artemis Accords”, available at: https://www.nasa.gov/artemis-accords/.

NASA. “Artemis Partners”, available at: https://www.nasa.gov/artemis-partners/.

Pekkanen, Saadia M. 2019. “Governing the New Space Race”. AJIL Unbound 113: 92–97, available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/aju.2019.16.

Robinson, Jana/Kukpová, Tereza B./Martínek, Patrik. 2020. “Strategic Competition for Space Partnerships and Markets”. In: Shrogl, K. (eds) Handbook of Space Security. Cham: Springer, available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23210-8_141.

Sheehan, Matt/Blumenthal, Marjory/Nelson, Michael R. “Three Takeaways From China’s New Standards Strategy”. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 October 2021, available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/28/three-takeaways-from-china-s-new-standards-strategy-pub-85678.

United Nations. “Agreement governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”. Treaty Collection, New York, 5 December 1979, available at: https://www.state.gov/united-states-welcomes-the-republic-of-angolas-signature-of-the-artemis-accords/.

United Nations. “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”. RES 2222 (XXI), 19 December 1966, available at: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/resolutions/1966/general_assembly_21st_session/res_2222_xxi.html.

U.S. Congress. “Department of Defense and Full-year Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011”. Public Law 112-10, 15 April 2011, available at: https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ10/PLAW-112publ10.pdf.

U.S. Department of Defense. 2023. “Military and Security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China”. Annual Report to Congress, available at: https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

U.S. Department of State. “United States Welcomes the Republic of Angola’s Signature of the Artemis Accords”. Media Note, Office of the Spokesperson, 4 December 2023, available at: https://www.state.gov/united-states-welcomes-the-republic-of-angolas-signature-of-the-artemis-accords/.

Vidal, Florian/Privalov, Roman. 2023. “Russia in Outer Space: A Shrinking Space Power in the Era of Global Change”. Space Policy, available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2023.101579.

White House. “Space Policy Directive-1, Reinvigorating America’s Human Space Exploration Program”. Presidential Memoranda, Washington, D.C., 11 December 2017, available at: https://2017-2021.state.gov/space-policy-directive-1-reinvigorating-americas-human-space-exploration-program/.

Footnotes

-

White House. “Space Policy Directive-1, Reinvigorating America’s Human Space Exploration Program”. Presidential Memoranda, Washington, D.C., 11 December 2017, available at: https://2017-2021.state.gov/space-policy-directive-1-reinvigorating-americas-human-space-exploration-program/. ↩

-

NASA. “Artemis Partners”, available at: https://www.nasa.gov/artemis-partners/. ↩

-

NASA. “Artemis Accords”, available at: https://www.nasa.gov/artemis-accords/. ↩

-

U.S. Department of State. “United States Welcomes the Republic of Angola’s Signature of the Artemis Accords”. Media Note, Office of the Spokesperson, 4 December 2023, available at: https://www.state.gov/united-states-welcomes-the-republic-of-angolas-signature-of-the-artemis-accords/. ↩

-

United Nations. “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”. RES 2222 (XXI), 19 December 1966, available at: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/oosadoc/data/resolutions/1966/general_assembly_21st_session/res_2222_xxi.html. ↩

-

United Nations. “Agreement governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”. Treaty Collection, New York, 5 December 1979, available at: https://www.state.gov/united-states-welcomes-the-republic-of-angolas-signature-of-the-artemis-accords/ ↩

-

China National Space Administration. “JOINT STATEMENT Between CNSA And ROSCOSMOS Regarding Cooperation for the Construction of the International Lunar Research Station”. 29 April 2021, available at: https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/english/n6465668/n6465670/c6811967/content.html. ↩

-

Sheehan, Matt/Blumenthal, Marjory/Nelson, Michael R. “Three Takeaways From China’s New Standards Strategy”. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 October2021, available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/28/three-takeaways-from-china-s-new-standards-strategy-pub-85678. ↩

-

U.S. Department of Defense. 2023. “Military and Security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China”. Annual Report to Congress, available at: https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF ↩

-

Robinson, Jana/Kukpová, Tereza B./Martínek, Patrik. 2020. “Strategic Competition for Space Partnerships and Markets”. In: Shrogl, K. (eds) Handbook of Space Security. Cham: Springer, available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23210-8_141. ↩

-

U.S. Congress. “Department of Defense and Full-year Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011”. Public Law 112-10, 15 April 2011, available at: https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ10/PLAW-112publ10.pdf. ↩

-

Cooper, Julian. 2021. “Russia’s updated National Security Strategy”. Russian Studies Series 2/21, available at: https://www.ndc.nato.int/research/research.php?icode=704#_edn1. ↩

-

Vidal, Florian/Privalov, Roman. 2023. “Russia in Outer Space: A Shrinking Space Power in the Era of Global Change”. Space Policy, available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2023.101579 ↩

-

Robinson, Jana/Kukpová, Tereza B./Martínek, Patrik. 2020. “Strategic Competition for Space Partnerships and Markets”. In: Shrogl, K. (eds.) Handbook of Space Security. Cham: Springer, available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23210-8_141. ↩