The Outer Space Treaty

The ‘Magna Carta’ of space law is the UN Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the so-called Outer Space Treaty or OST). The Outer Space Treaty institutionalised the framework for outer space activities.

The Treaty entered into force in 1967 during the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union and security was a key element. Its purpose was to prevent space from becoming another area of conflict. This is why, for example, the Treaty established the concepts of non-appropriation of outer space, the freedom of exploration, the prevention of harmful interference with space activities and the environment, as well as principles of peaceful cooperation and scientific exploration.

The Outer Space Treaty banned the ‘placement of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction’ in space and emphasised that space is only to be used for ‘peaceful purposes’.

However, the Treaty only bans the placement of nuclear weapons in space, not their development and testing (though testing was banned by the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space, and Under Water). Nor does the Outer Space Treaty specifically prohibit the use of nuclear ballistic missiles travelling through space due to its focus on preventing the placement of nuclear weapons in orbit or on celestial bodies. Since the Treaty was negotiated during the Cold War era when nuclear deterrence strategies were prevalent, achieving consensus on a complete ban on nuclear weapons in space proved challenging. Moreover, the Treaty does not ban the placement of conventional weapons, such as co-orbital mines, in space, nor does it address ballistic missiles – nuclear equipped or not – that ascent to and move through space. As the last space treaty – the Moon Treaty – was signed as long ago as 1979, there are concerns about whether this body of law, developed during the Cold War, is sufficient to address the much more complex situations in space today

As negotiating amendments to the Outer Space Treaty or signing a new Treaty would possibly be a decades-long process, countries have engaged in various other initiatives to strengthen space governance. Some countries, such as Russia and China, promote the concept of ‘arms control for space’ whereas others, such as European countries and the United States, lean towards responsible norms of behaviour in outer space-related initiatives. Due to the inherent dual-use nature of space technologies, arms control proposals for space are problematic, mainly because of the issue of verification.

UN Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies

The Outer Space Treaty (1967) establishes that outer space, including the Moon and celestial bodies, is free for exploration and use by all nations. It prohibits the placement of nuclear weapons in space, claims of sovereignty, and military activities. The treaty emphasizes peaceful purposes and international cooperation.

Current Adoption

The Hague Code of Conduct

The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC) is a set of voluntary norms seeking to address missile proliferation. Given the similarities between the technologies used in ballistic missiles and civilian rockets, the Hague Code also introduces transparency measures such as annual declarations and pre-launch notifications regarding ballistic missile and space launch programs. The HCoC also states that ‘Space Launch Vehicle programs should not be used to conceal Ballistic Missile programs’.3 The HCoC was signed and entered into force in 2002 in the Hague (Netherlands). As of June 2023, a total of 143 nations had joined the HCoC (141 United Nations members, the Cook Islands and the Holy See).4 However, the Hague Code of Conduct does not contain an effective verification and compliance mechanism. It also faces issues related to non-compliance.

The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation

The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC) is a multilateral, voluntary initiative aimed at preventing the spread of ballistic missiles capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Established in 2002, it complements existing non-proliferation measures like the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). The HCoC promotes transparency and confidence-building through annual declarations on ballistic missile and space-launch programs, as well as pre-launch notifications. While not legally binding, it encourages responsible behavior among its 145 subscribing states, serving as a critical tool for global security by fostering dialogue and cooperation to limit the proliferation of missile technologies.

Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities

etween 2010 and 2018, the UN COPUOS working group negotiated what are known as Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities (LTS Guidelines). In June 2018, a total of 21 guidelines were adopted. The UN COPUOS guidelines are not legally binding. However, the states who have adopted the guidelines are responsible for the security and safety of space activities and may implement these rules into national legislation. Such steps are crucial, not only for states themselves but also for commercial and other non-state actors. Although the adoption of 21 guidelines was considered a substantive success, space activities are rapidly evolving, and the rules that were negotiated arguably do not sufficiently reflect the dynamic development of the space sector. Instead, they should be seen as the groundwork for developing a new set of guidelines, the LTS 2.0, in the near future.

Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects

Prevention of an arms race in space (PAROS) has been on the agenda since 1985. A draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects (PPWT) was first proposed by China and Russia in 2008, and a revised version in 2014. In 2004, Russia pledged at the UN General Assembly First Committee ‘not to be the first to place weapons of any kind in outer space’. However, the draft treaty was opposed by the United States due to its significant flaws. The PPWT, for instance, does not address direct ascent kinetic anti-satellite weapons, nor does it propose efficient verification mechanisms or exact definitions. Moreover, Russia irresponsibly tested a direct ascent kinetic anti-satellite weapon in 2021 and recently demonstrated advanced orbital operations that could relate to the testing of co-orbital anti-satellite weapons.

Reducing space threats through norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors

Due to the verification issues created by the dual-use nature of space technology and weapons, the alternative approach to the arms control of outer space is a gradual implementation of new norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviour that can create the foundation for viable legally binding arms control treaties in the future. The most notable initiative in this regard, building on the European Code of Conduct from 2012, is the ‘Reducing space threats through norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors’ resolution that was first adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2020. As part of this resolution, an open-ended working group (OEWG) has been established with the goal of making recommendations to the General Assembly. This norm-oriented resolution endorses a ‘bottom-up’ approach to space arms control and is widely supported by democratic states. However, countries like Russia and China are opposed to such initiatives and are stalling the process.

Destructive direct ascent anti-satellite missile testing

In 2022, the United States declared a self-imposed ban on direct ascent destructive anti-satellite weapons tests, further promoting new norms for responsible behaviour in outer space. While visiting Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on April 18, 2022, US Vice President Kamala Harris declared in regard to destructive anti-satellite tests:

“I am pleased to announce that as of today, the United States commits not to conduct destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing. Simply put: These tests are dangerous, and we will not conduct them. We are the first nation to make such a commitment. And today, on behalf of the United States of America, I call on all nations to join us. Whether a nation is spacefaring or not, we believe this will benefit everyone, just as space benefits everyone. In the days and months ahead, we will work with other nations to establish this as a new international norm for responsible behavior in space. And there is a direct connection between such a norm and the daily life of the American people.”

Remarks by Vice President Kamala Harris on the Ongoing Work to Establish Norms in Space.

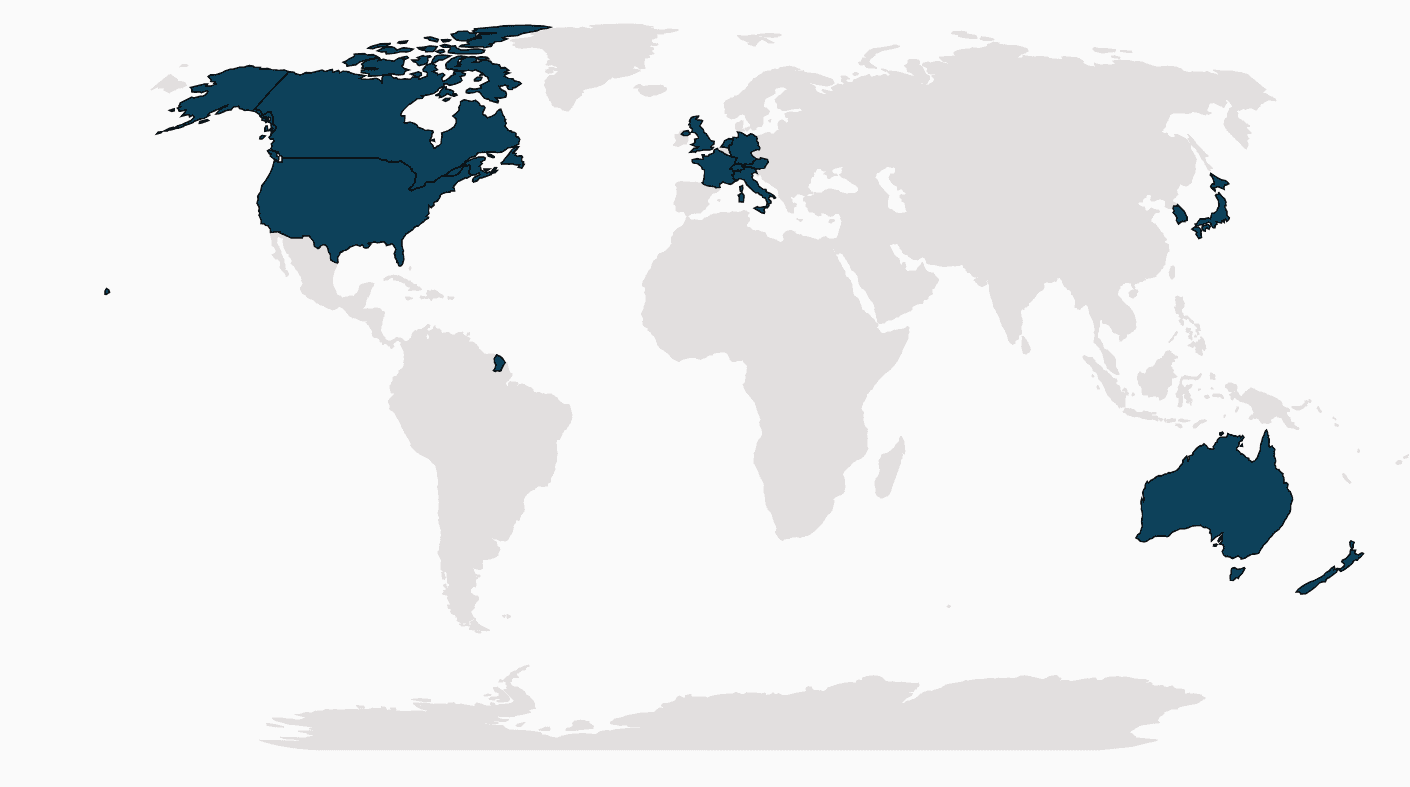

As of July 2023, a total of 14 nations had joined this commitment, including, alongside the United States, Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Korea, Switzerland, Lithuania and the United Kingdom

In December 2022, the UN General Assembly approved a ‘Destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing’ resolution that ‘calls upon all States to commit not to conduct destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests5’. A total of 155 nations voted in favour of the resolution. However, nine countries, including Russia and China, opposed it. Moreover, UN resolutions are not legally binding. It would therefore be welcomed if more nations were to make official commitments to this international norm, which would reinforce space arms control and peaceful uses of outer space.

Conclusion

The governance of outer space, established through UN bodies and treaties such as the Outer Space Treaty, aimed to prevent space from becoming a battleground. However, challenges persist due to evolving technologies as well as disagreements among nations. Efforts to address the situation include arms control proposals and promoting responsible behaviour in space activities. Despite initiatives such as self-imposed bans on certain types of testing, global alignment on these commitments remains a challenge. Strengthening space governance requires updated frameworks that take technological advancements into account while fostering international cooperation for peaceful space exploration.

Quiz

Sources for this chapter

“Conference on Disarmament (CD)”. The Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2023, available at: https://www.nti.org/education-center/treaties-and-regimes/conference-on-disarmament/.

“Destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing”. 2022, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/738/92/PDF/N2273892.pdf?OpenElement.

“List of HCoC Subscribing States”. The Hague Code of Conduct, 2020, available at: https://www.hcoc.at/subscribing-states/list-of-hcoc-subscribing-states.html.

“Text of the HCoC”. The Hague Code of Conduct, 2012, available at: https://www.hcoc.at/what-is-hcoc/text-of-the-hcoc.html.

United Nations. 2023. “Space Law Treaties and Principles”. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, available at: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties.html.

Footnotes

-

“Conference on Disarmament (CD)”. The Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2023, available at: https://www.nti.org/education-center/treaties-and-regimes/conference-on-disarmament/. ↩

-

United Nations. 2023. “Space Law Treaties and Principles.” United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, available at: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties.html. ↩

-

“Text of the HCoC”. The Hague Code of Conduct, 2012, available at: https://www.hcoc.at/what-is-hcoc/text-of-the-hcoc.html . ↩

-

“List of HCoC Subscribing States”. The Hague Code of Conduct, 2020, available at: https://www.hcoc.at/subscribing-states/list-of-hcoc-subscribing-states.html. ↩

-

“Destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing”. 2022, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/738/92/PDF/N2273892.pdf?OpenElement ↩