Definition and humanitarian problems

Anti-personnel landmines, which include some of the simplest and most common weapons, are banned by a treaty adopted in 1997 and ratified by 164 states (as of September 2024). What are anti-personnel landmines and why were they banned?

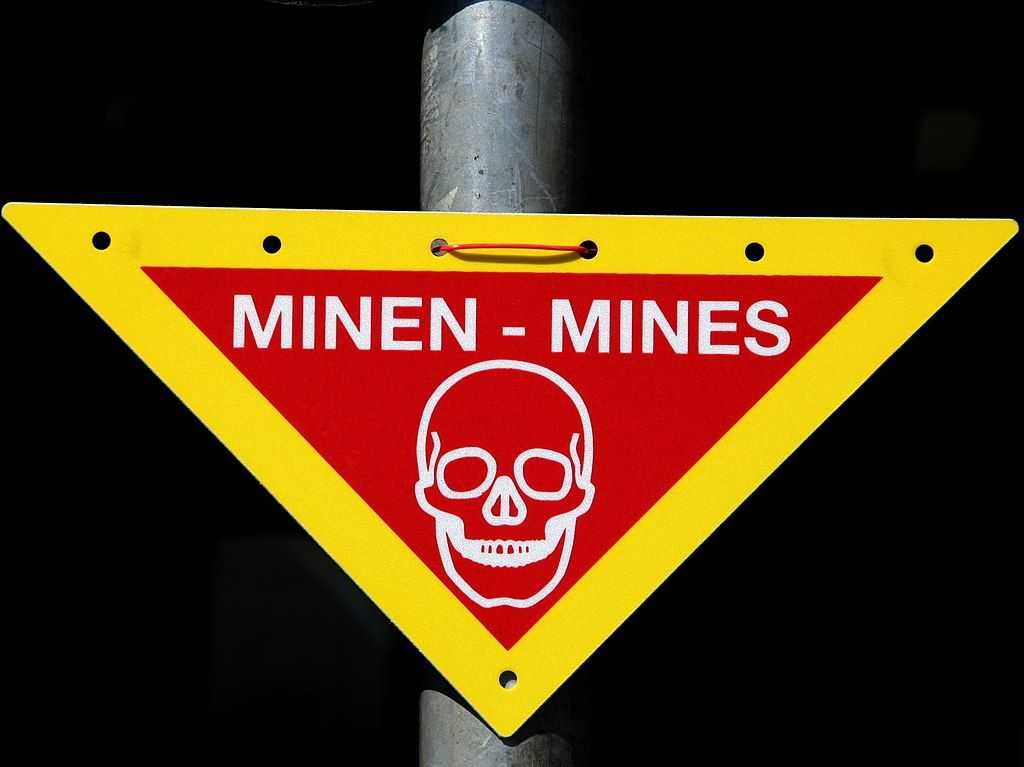

There is a common understanding that a mine is a concealed explosive that detonates when someone unwittingly steps on it. It is a hidden and explosive danger, waiting to strike unexpectedly.

A more technical description is that anti-personnel landmines (APL) are explosive devices, designed to detonate when disturbed by the presence, proximity or contact of a person, who is then injured or killed. Most surviving victims have to undergo amputations. Once placed under or on the ground, APLs can stay active for decades.1 The large majority are victim-activated – detonated by pressure or trip-wire when a person walks on or near them. In contrast, anti-vehicle mines are designed to explode with the much heavier weight of a vehicle. Some mines are command-detonated, for example by radio signal, and require a human decision to explode.

Mines are used for several main purposes – to prevent the deactivation of anti-tank mines, to create defensive barriers around military positions, to deny territory to, slow down, or channel enemy forces to specific areas where they will then be fired upon.

Anti-personnel landmines are typically small, usually about 7–16 cm in diameter and 5–10 cm in height.2 The simplest models can cost as little as three US dollars.3 With the invention of remotely delivered types, air-dropped or ground-launched mines could be dispersed in great numbers over large territories. Given their simple design and low cost, APLs have been widely used by non-state armed groups. Thus, a combination of new delivery methods, low cost and use by non-state actors led to rampant landmine contamination in the 1980s. Demining, in contrast, is costly and slow. Although self-destructing or self-deactivating mines were developed during the Cold War, they had reliability issues and posed similar challenges for demining to older models.

In the 1990s, during a time of relative peace when the Cold War had come to an end and proxy civil wars were receding, it was estimated that around 26,000 people fell victim to landmines each year. Ordinary people, about half of them children, were being maimed and killed. Agricultural land, mostly in countries in the Global South, on which people depended to make a living was contaminated in ‘epidemic proportion’, in the words of Jody Williams who in 1992, became the coordinator of an NGO network, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) to address the problem. Five years later, a treaty comprehensively banning anti-personnel landmines (APL) was adopted.

So why were landmines singled out for prohibition? To quote Williams again:

Landmines distinguish themselves because once they have been sown, once the soldier walks away from the weapon, the landmine cannot tell the difference between a soldier or a civilian – a woman, a child, a grandmother going out to collect firewood to make the family meal. The crux of the problem is that while the use of the weapon might be militarily justifiable during the day of the battle […] once peace is declared the landmine does not recognize that peace. The landmine is eternally prepared to take victims

Source: Jody Williams 1997

Or as expressed by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC):

The limited military utility of AP mines is far outweighed by the appalling humanitarian consequences of their use in actual conflicts

Source: ICRC 1996, 73

Thus, from a legal and a humanitarian perspective, anti-personnel landmines were indiscriminate weapons whose humanitarian impact exceeded whatever military value they may have had.

Another aspect of the problem, the gruesome and graphic injuries they inflicted on innocent civilians, especially children, made a particularly strong and emotional impact on public opinion.

Context mattered, too. At the end of the Cold War, immediate security threats in the West and the East had subsided, allowing other issues, such as human rights and development, to move up the international agenda. At the same time, smaller states could forge a more independent path without being bound to the great powers’ wishes.

Non-governmental organisations working on human rights, development and humanitarian issues were able to gather first-hand information about mine contamination and casualties. They became the experts providing information on the issue and framing it to resonate with existing legal frameworks and public opinion. These organisations were the active force behind the ban. The next section will outline some of the main aspects of their campaign.

The NGO campaign

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as proxy civil wars came to an end, an increasing number of NGOs moved in to assist with post-conflict reconstruction – and found themselves confronted with the landmine problem. The scale of the human, social and economic toll of landmine contamination in Cambodia, Angola, Colombia, Mozambique, or Afghanistan was staggering. Humanitarian, medical and human rights organisations had to deal with the consequences and before long started compiling information about the issue and reflecting on ways to address it. In addition to providing assistance to victims and clearing mines, in 1992, several organisations launched the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). These organisations saw a ban as the only way of tackling the root cause of the problem. Given that landmines were small, cheap and available in great numbers, while mine clearance was difficult, time consuming and costly, clearance alone was not enough to put an end to the landmine threat. Supply also needed to be stopped and a stigma around mines created so that even when they were easily-available, combatants would be reluctant to use them.

In 1994, having witnessed the horrendous effects of landmines through the work of its surgeons and fieldworkers, the ICRC also decided to call for a ban and launched an extensive public campaign on the issue.4 The NGO strategy centred on gathering and publicising information about the scale of mine contamination, the long-term human suffering faced by victims and the obstacles to socio-economic development. They reframed the debate in humanitarian terms. They argued that the humanitarian costs of these weapons far outweighed their military utility and shifted the burden of proof – now those insisting on retaining landmines had to defend their positions and show that APLs did not in fact cause serious humanitarian harm and were not simply useful to the military, but indispensable weapons.5

The CCW was the logical forum to address the landmine problem and NGOs convinced France to call for a review conference and place the ban on the CCW agenda. The CCW adopted Amended Protocol II, which strengthened provisions regarding the inclusion of self-neutralisation mechanisms in landmines, recording and marking of minefields and mine clearance on territory controlled by states parties. It also banned non-detectable mines. However, this was not a comprehensive ban and fell short of expectations. Nevertheless, the CCW talks provided an opportunity for NGOs to advocate for a ban, lobby delegates and importantly, foster relationships with government officials. As government policies gradually shifted from export bans, to moratoria on use, to domestic bans on APLs, Canada decided to organise a separate conference to capitalise on the momentum created for a ban. At this conference, held in October 1996, Canada announced its initiative to work for total prohibition of APL and called for governments to support it.

The Ottawa Process to ban anti-personnel landmines

The historical development

What followed became known as the Ottawa Process, a fast-track, ad hoc negotiation process led by a few likeminded small and medium-sized states,6 but opposed by the main military powers. It involved close cooperation with the ICRC and ICBL and emphasised the human dimension of the problem. Landmine survivors were active players and placed the process on a human plane, making it different from traditional diplomacy and arms control. In procedural terms, the Ottawa Process comprised a number of regional conferences to rally support for the ban, especially among mine-affected countries in the Global South, and negotiation conferences to flesh out the treaty provisions. After a whirlwind campaign, the treaty banning anti-personnel landmines was adopted in September 1997 and signed by 122 states in December.

Timeline of the Ottawa Process leading to the MBT

- Oct. 1992

ICBL created by the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation (US), Medico International (Germany), Human Rights Watch (US), Handicap International (now Humanity and Inclusion) (France), Physicians for Human Rights (US) and the Mines Advisory Group (UK). US moratorium on the export of APLs

- Apr. 1993

ICRC organises ‘Symposium on Anti-Personnel Mines’

- May 1993

First International NGO Conference on Landmines, London

- Sept. 1993

UNICEF gives priority attention to the issue of landmines and provides support to the ICBL

- Feb. 1994

ICRC President Cornelius Sommaruga declares that a ‘worldwide ban on anti-personnel mines is the only truly effective solution’

- May 1994

Second International NGO Conference on Landmines, Geneva

- Sept. 1994

UN Secretary-General’s first report on mine clearance notes that the ‘best and most effective way’ to solve the global landmine problem is a complete ban of all landmines. US President Clinton calls for the ‘eventual elimination’ of landmines

- Mar. 1995

Belgium becomes the first country to pass domestic laws banning the use, production, procurement, sale and transfer of APLs

- Jun. 1995

The Norwegian parliament adopts a binding resolution calling upon its government to work towards a complete ban on APLs. The Cambodia Campaign to Ban Landmines and the NGO Forum on Cambodia organise an international conference on APLs in Phnom Penh

- Oct. 1995

CCW Review Conference

- Nov. 1995

Switzerland and Canada announce that they favour a complete and immediate international ban on APLs

- Jan. 1996

The CCW Review Conference reconvenes in Vienna to discuss ‘technical issues’ related to controlling landmine use. Canadian moratorium on the use, production, trade and export of APLs

- Apr. 1996

Canada announces decision to organise a strategy meeting on ways to address the APL problem beyond the CCW

- May 1996

CCW adopts Amended Protocol II on mines, featuring provisions on mine reliability, recording and clearance

- Jun. 1996

The Organization of American States adopts a resolution providing for the establishment of a hemisphere-wide landmine-free zone

- Oct. 1996

Ottawa Conference on APLs launches the mine ban process

- Feb. 1997

Austria hosts the first Ottawa Process preparatory conference to discuss provisions for inclusion in the Mine Ban Treaty. ICBL organises an International NGO Conference on Landmines in Maputo, Mozambique

- Mar. 1997

Tokyo Conference on Anti-Personnel Landmines, organised by the Association for Aid and Relief

- Apr. 1997

A technical meeting on verification and compliance measures to include in the MBT organised by Germany. A regional seminar on landmines for States of the Southern Africa Development Community in Harare, organised by the ICRC, together with the OAU and Zimbabwe

- May 1997

Seminar on Anti-Personnel Mines and Strategy Workshop for countries of the Baltic and Eastern European Region in Stockholm. 25 African governments commit to signing the MBT at the OAU meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa

- Jun. 1997

Belgium organises the second Ottawa Process preparatory conference. Central Asia Regional Conference organised by ICBL and the ICRC and the governments of Turkmenistan and Canada in Ashgabat

- Sept. 1997

Norway hosts the negotiation conference of the MBT

- Oct. 1997

ICBL and its coordinator Jody Williams are awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

- Dec. 1997

Ottawa Conference for the signing of the MBT

This process, characterised by the partnership between NGOs and state norm entrepreneurs, has been dubbed ‘new diplomacy’7 and a ‘new kind of “superpower”’8 for the development of humanitarian norms. It also became a model (with some variations) for a number of processes, including the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court in 1998, the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Mine Ban Treaty remains the archetypal example of humanitarian arms control. In recognition of their role in it, the ICBL and its coordinator, Jody Williams, received the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize.

Provisions of the Mine Ban Treaty

Status of the Mine Ban Treaty

Currently, the Convention is ratified by 164 states. This includes many of the countries who had been the biggest landmine producers in the past, such as Belgium, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy and the United Kingdom, as well as states with largescale APL contamination, such as Afghanistan, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia and Mozambique. All 27 EU member states and all but one (the US) NATO member states are states parties.

Despite this widespread support for the Convention, major military powers, including China, India, Pakistan, Russia and the US, remain outside of it. There is evidence that stigmatisation has had an effect on US policies – since the adoption of the MBT, the US has been in de facto compliance with the ban on use, export and transfer (except for a single mine used in Afghanistan), and in 2022, the Biden administration declared the country’s commitment to eventually rejoining the treaty.12 Unfortunately, this de facto support for the MBT’s core provisions was broken in November 2024 when the US decided to transfer APLs to Ukraine.13

Since the adoption of the MBT, more than 55 million anti-personnel landmines have been destroyed and since the mid-1990s, there has been a de facto global ban on APL transfer14 until the US decision to provide Ukraine with APLs.

Many states no longer produce APLs – of the over 50 past producers, 12 remained in 2023, only five (India, Iran, Myanmar, Pakistan and Russia) of which are believed to be actively producing mines.15

Footnotes

-

Some mines are fitted with self-destruct or self-deactivation mechanisms that have to render them harmless after a certain period of time. ↩

-

UN Mine Action Service 2015, 13. ↩

-

U.S. Department of State 1994. ↩

-

Maslen 2004. ↩

-

Price 1998; Petrova 2018. ↩

-

These included Austria, Belgium, Canada, Norway, Mexico, South Africa and Sweden; Cameron 2002. ↩

-

McRae and Hubert 2001; Cooper et al. 2002. ↩

-

Williams 1997. ↩

-

A device intended to protect a mine and which is part of, linked to, attached to or placed under the mine and which activates when an attempt is made to tamper with or otherwise intentionally disturb the mine. ↩

-

Wareham 2008. ↩

-

This has been an official objective since 1997, although the Trump administration dropped it in 2020. ↩

-

‘Biden approves antipersonnel mines for Ukraine, undoing his own policy’, Washington Post, 19 November 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2024/11/19/biden-landmines-ukraine-russia/. ↩

-

Landmine Monitor 2022, 24. ↩

-

Landmine Monitor 2023, 23. ↩