The CFE Treaty

This chapter will discuss the three main parts of the European conventional arms control system developed in the 1990s. The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty, the Open Skies Treaty and the Vienna Document on Confidence and Security-Building Measures. Together, they formed the foundation of the cooperative approach to security and, despite the recent setbacks, provide a point of reference for potential future work on re-establishing arms control in Europe.

The CFE Treaty: Numbers and definitions

The CFE Treaty (II): Implementation, problems and path to irrelevance

CFE-Treaty Factsheet

Name: Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE)

Members 23

Effective 9 November 1992

Aims:

- Create a stable balance of conventional forces in Europe with lower levels of stocks of major weapons

- Limit the possibility of a surprise, large-scale attack

- Maintain stability through exchange of information and a verification system, including on-site inspections

Signed: 19 November 1990

Entry into force: 9 November 1992

State parties: 22 at the time of signing. 30 at the time of entry into force (including eight former USSR republics). 29 in 2025 - Russia withdrew from CFE implementation in 2023. Six other state parties suspended their observation of CFE but not withdrew (Belarus, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Turkey, United States).

Area of application: Territories of the European state parties from the Atlantic to the Ural Mountains

Treaty-Limited Equipment (TLE): Tanks, armoured combat vehicles, heavy artillery, combat aircraft and attack helicopters

Limitations: Ceilings established for each ‘side’ (NATO and the Warsaw Pact), further internally divided into national entitlements: 20,000 tanks; 30,000 armoured combat vehicles; 20,000 heavy artillery pieces; 6,800 combat aircraft; 2,000 attack helicopters.

TLE eliminated: Approximately 52,000 excess pieces of TLE eliminated within the area of application; 69,000 eliminated pieces including additional voluntary actions

Flank regime: Restriction on numbers of tanks, armoured combat vehicles and heavy artillery in specified areas of Northern and Southern Europe

Verification: System of information exchange, on-site inspections of the units declared to be armed with TLE, challenge inspections (to undeclared sites there TLEs may be held), monitoring of destruction, conversion inspections

Adopted CFE Treaty: Signed in 1999, ratified by Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Ukraine – not in force

Member countries (in 2025): Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Kazakhstan, Luxembourg, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States

Open Skies Treaty

The Open Skies Treaty was first proposed by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower in 1955. The president’s idea was that the United States and the Soviet Union would allow reconnaissance overflights of each other’s territory to make sure that no surprise attack was planned. Unfortunately, the proposal was rejected by the Soviet Union as an attempt to sanction spying.

Towards the end of the Cold War, political relations between the two superpowers improved significantly. When the idea of observation flights was reintroduced by the US in 1989, it was picked up by a number of NATO and Warsaw Pact countries. After three years of negotiations, the Open Skies Treaty was signed in 1992. 1

The Treaty entered into force in 2002. As of early 2020, there were 34 state parties to the Treaty, covering the area from Vancouver to Vladivostok.

Map showing member states of the Open Skies Treaty

Data: Natual Earth. Graphic: PRIF

The basic characteristics of the Open Skies regime are:

- The flights can only be conducted by unarmed, specially certified aircraft.

- Overflights can take place over the whole territory over which a state party exercises sovereignty, including the land, islands, internal and territorial waters – no areas or military installations are off-limits.

- Images from the flights are shared by the observing and observed country. They are also made available to other state parties, but these must specifically request and pay for them.

- Each aircraft can carry only specially certified sensors: video cameras, optical cameras, infrared sensors and synthetic aperture radar (allowing images of objects to be created).

- Introduction of new technology – for example use of digital camera instead of film – must be agreed by all parties. The quality of the images should be sufficient to permit recognition of major military equipment.

- Each state is assigned a specific quota of observation flights that it is obliged to receive every year (passive quota), and it is permitted to conduct the same number of flights in other parties itself (active quota).

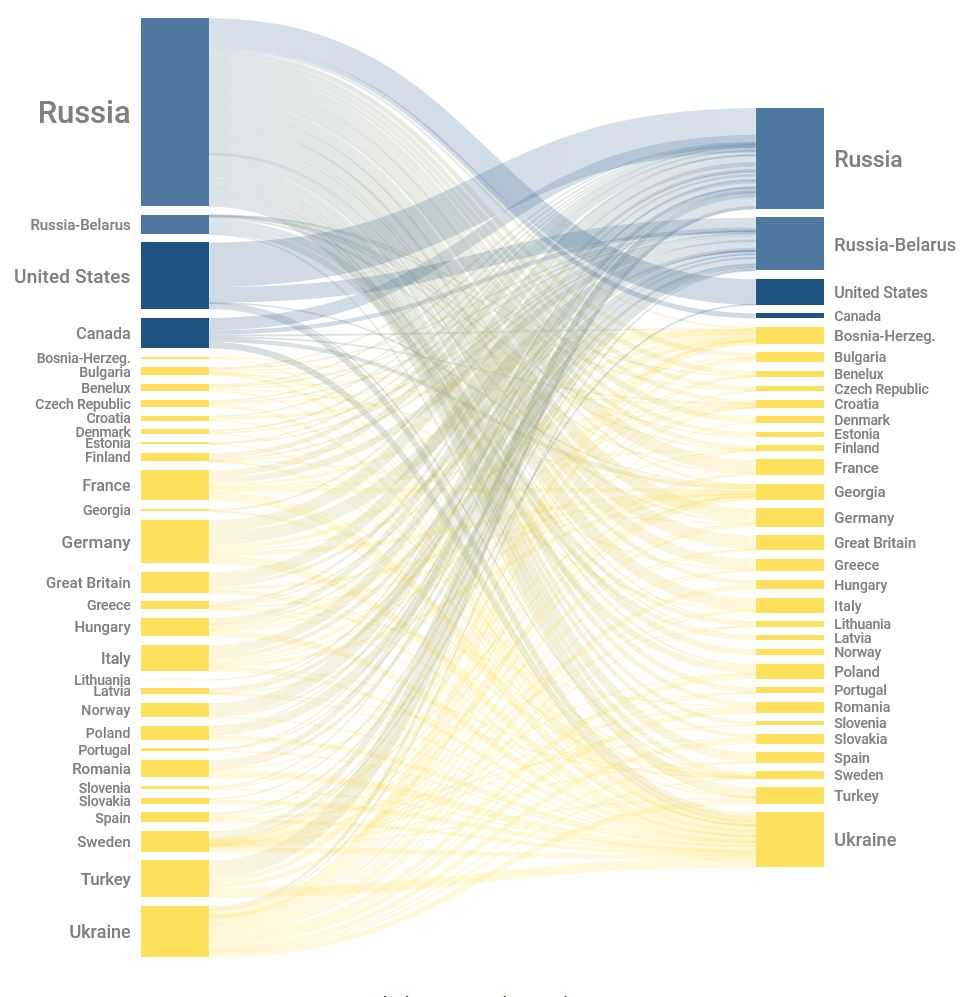

Treaty Quotas of the Open Skies Treaty

Data: Council on Strategic Risks, Graphic: PRIF

Before the Open Skies Treaty entered into force in 2002, around 350 trial flights took place. Since then, around 100 observation flights have been conducted every year. The year 2013 saw the 1,000th observation flight conducted under the Open Skies and in October 2019 – the 1,500th flight. The Open Skies Treaty website offers an interesting and interactive visualisation of the flights between 2002 and 2019.

Observation flights under the Open Skies Treaty are meant to:

- improve openness and military transparency between all the parties through cooperative actions;

- contribute to conflict prevention and crisis management (for example, Open Skies overflights were used in 2013 and 2014 to monitor the deployment and movement of Russian forces in the vicinity of Ukraine);

- double-check the information provided by a particular country about its military posture through other agreements and confidence-building regimes, such as the Vienna Document, and help monitor compliance with them.

Throughout the existence of the Treaty, there were also implementation issues and disputes, for example connected with overflights in the border areas (e.g. between Russia and Georgia, or along Turkey’s border with Syria), as well Russia’s imposition of a 500-kilometre limit for certain observation flights over Kaliningrad. In the US internal debate, it was also argued that Russia was obtaining significantly more intelligence benefits from the data collected under the Treaty, and modernising its data-collecting aircraft, whereas the importance of the Treaty for the US was less clear, given the availability of high-quality data from its satellites.

These arguments led the Trump administration to announce the US withdrawal from the Open Skies Treaty in May 2020. The decision was based on allegations of repeated Russian violations of the Treaty. The withdrawal took effect on 22 November 2020. This was followed immediately by Russia moving to pull back from the Treaty, with its withdrawal becoming effective in December 2021.

The Treaty on Open Skies remains in operation for the remaining 32 states, and some observation flights still take place. But without US and Russian participation, its relevance for European security is limited.

The Vienna Document

Dealing with unusual military activities: the Vienna Document’s risk reduction procedure

The following outlines the Vienna Document’s risk reduction procedure as regards unusual military activities (see Chapter 3 paragraph 16):

-

Concerns about an unusual and unscheduled activity of another state’s military forces outside their normal peacetime locations which are militarily significant and are within the zone of application for CSBMs

🠗

-

Request for an explanation, stating the cause of concern and the type and location of activity (transmitted to all OSCE participating states)

🠗

-

Reply, delivered to requesting state within no more than 48 hours (transmitted to all OSCE participating states)

🠗

- Concerns dispelled, reply accepted; 2. Concerns not dispelled

🠗

-

Request for a meeting with the responding state (transmitted to all OSCE states)

🠗

-

Meeting convened within no more than 48 hours, with the presence of other invited interested states, under the chairmanship of the OSCE Chairman-in-Office (CiO) or his/her representative.

🠗

-

Report from the meeting prepared by the CiO or representative and sent to all OSCE states

🠗

- Concerns dispelled, situation stabilised; 2. Concerns not dispelled

🠗

-

Meeting of all participating states in the forum of the OSCE Permanent Council (PC) and the Forum for Security Co-operation (FSC), convened by CiO within 48 hours on the initiative of either the requesting or responding state

🠗

-

The PC and FSC assess and recommend appropriate measures for stabilising the situation and halting activities that give rise to concern

A number of weaknesses of the Vienna Document have been identified since its last update in 2011. Since it is not a legally binding instrument, its implementation by a particular country relies to large extent on that country’s good will and ‘peer pressure’ from other participants.

Weaknesses of the Vienna Document

Information exchange

The scope of the Vienna Document’s information exchange on military forces and weapons does not cover some important elements of modern armed forces, including missile systems, naval forces and uncrewed vehicles.

Notification thresholds

The thresholds for notification and observation of exercises are seen as too high. The majority of military exercises that have taken place in Europe were smaller and fell below the thresholds. Moreover, the so-called ‘surprise’ or ‘snap’ exercises, even the largest-scale ones, do not have to be announced in advance, which constitutes a loophole.

Risk reduction mechanisms

The risk reduction mechanisms, including for unusual or unscheduled military activities, depend on the cooperation of the country where the activity is taking place, which may not always be forthcoming.

The implementation of the Vienna Document has also been negatively affected by the increased tensions in Europe and by Russia’s war on Ukraine.

In particular, the Vienna Document’s risk reduction mechanism for unusual and unscheduled activities was used in 2021 and 2022 to raise the alarm about military activities in Belarus and Russia in the vicinity of the Ukrainian border, but the procedure did not dispel concerns or change Russia’s war plans. In February 2022, Russia refused to attend the joint session of the Permanent Council and the Forum for Security Co-operation to assess the situation regarding its unusual military activities (see the procedure above).

Russia accused a number of other participating states of not providing the required information and notifications about their military activities and exercises, and in 2023, it announced that it would no longer be providing information about its armed forces within the framework of the Vienna Document’s annual exchange.2

Quiz

Footnotes

-

On the history of Open Skies Treaty and its negotiations, see https://unidir.org/files/publication/pdfs/open-skies-a-cooperative-approach-to-military-transparency-and-confidence-building-319.pdf ↩

-

Hernández, Gabriela Iveliz Rosa. 2023. How Russia’s retreat from the Vienna Document information exchange undermines European security, 24 May 2923, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, available at: https://thebulletin.org. ↩