Early attempts against Chemical Weapons

Early Constraints on Chemical Warfare

Early bans on poisoned weapons

The Manusmrti, a foundation of Hindu law

The Manusmrti, a foundation of Hindu law, contains the earliest recorded prohibition on use. It is over 2,000 years old. History also shows that cultures in different parts of the world adopted similar codes. However, the unilateral codes were not legally binding for the enemy.

Religions opposed indiscriminate warfare, which is the root of the ban on poisons. In Islam, this evolved from the prohibitions on flooding and fire in the 10th century. Christianity began framing similar codes in the Middle Ages. However, these applied only to one’s own religious community. The diaspora prevented Judaism from developing similar rules.

With the rise of the sovereign state, formal codification of the rules of war began in multilateral conferences during the second half of the 19th century. The industrial revolutions also generated the first interest in arms control, but constraining technology was an idea whose time had not yet come.

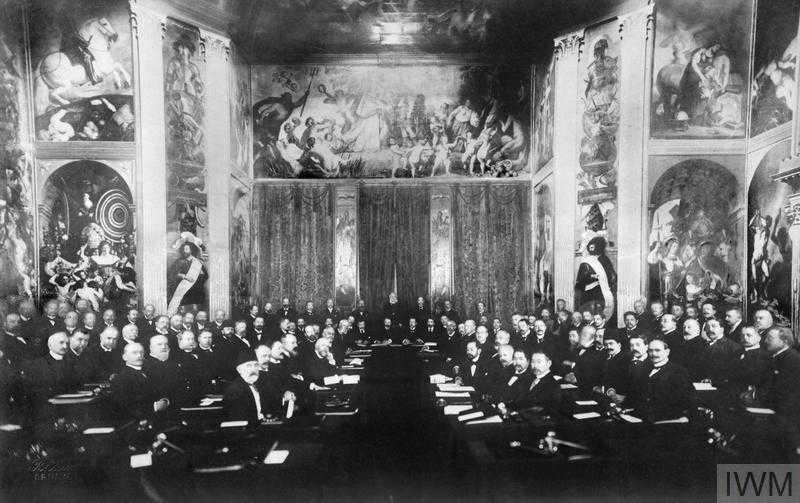

First Hague Peace Conference

Fearing the impact of industrialisation on armaments, Russia, an agrarian society, convened the 1899 Hague Peace Conference. The meeting failed to limit armaments, but with the Hague Convention (II) and the annexed Regulations it codified the laws and customs of war on land. The document included an overall ban on the use of poison and poisoned weapons.

In recognition of technological progress, the Conference also concluded Declaration (IV,2) Concerning Asphyxiating Gases, outlawing the use of projectiles designed to diffuse asphyxiating or deleterious gases. The focus of the regulation, however, was on ‘use’, not the weapon as such.

The 1907 Hague Conference updated the Convention with its Regulations but maintained the Declaration on asphyxiating gases. Most independent states at the time signed the document.

In 1915, the first large-scale chemical attack of World War I circumvented the prohibition because the chlorine gas used was released from cylinders in the trenches rather than being delivered by projectiles.

The Geneva Protocol

The 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibits chemical and biological methods of warfare. It is a direct descendant of the 1899 Hague Declaration (IV,2) and the 1919 Versailles Treaty banning Germany from using .

Even though the Geneva Protocol was never violated for biological warfare, on several occasions, it was unable to prevent CW use. However, nations came together each time to renew their commitment to the agreement. Thus, it gradually became part of customary law and is now seen as universally binding and applicable to any type of armed conflict.

Today, it offers the legal foundation for the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biolgical Weapons. Its language has also been incorporated into the 1998 Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court.

Breakthrough: The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC)

After the negotiations and adoption of the Geneva Protocol in 1925, it took more than 50 years for negotiations on a significantly more comprehensive treaty to start within the UN Conference on Disarmament. In the 1930s, the League of Nations (the precursor to the United Nations) convened the Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments, which, if successful, would have led to a comprehensive ban on chemical weapons. The meeting ended in failure in 1934 as a consequence of Japan’s invasion of China, Italy’s war of conquest in Ethiopia and the armaments build-up in Europe. After World War II, nuclear weapons and the Cold War dominated security considerations. However, systematic CW use by the US in the Viet Nam War led the UN General Assembly to adopt several resolutions expressing the need to strengthen the Geneva Protocol in the second half of the 1960s and studies into the consequences of chemical and biological warfare were requested by the UN Secretary-General and the World Health Organisation.

These developments contributed to chemical and biological weapon disarmament being put on the agenda. The separation of biological weapons from chemical weapons led to the adoption of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention in 1971 and its entry into force in 1975. Meanwhile, a CW ban languished until the 1980s. Especially after the US introduced a draft convention in 1984, negotiations intensified and picked up speed towards the end of the decade because of CW use in the Iran–Iraq War. Negotiators concluded the CWC in 1992 and it entered into force in 1997.

Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction

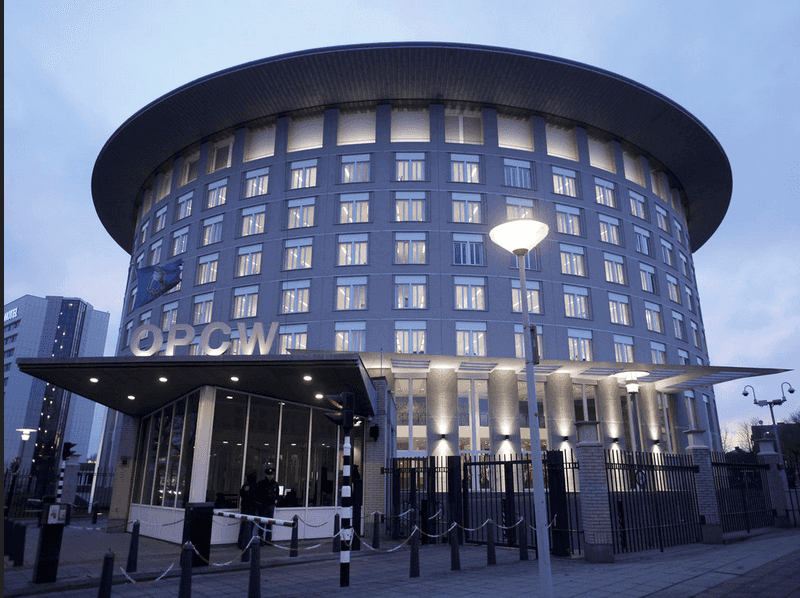

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) is a multilateral treaty that bans the development, production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons and prescribes their destruction. The CWC is binding under international law and its implementation is monitored by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

Current Adoption

Genesis and structure of the CWC

Success

When the CWC entered into force in 1997, overseeing the destruction of declared chemical weapons and installations associated with their production and storage was one of the OPCW’s biggest responsibilities and challenges. Eight countries declared chemical weapons arsenals with a total of 72,304 metric tons of warfare agents and 417,833 items, including munitions and containers. On 7 July 2023, the OPCW certified the destruction of all declared CW.

The Chemical Weapons Convention has been successful in eliminating all declared chemical weapon stockpiles. As of April 2024, a total of 193 states have ratified or acceded to the CWC, making the treaty as good as universal.

Reinforcing the norm against Chemical Weapons

While the CWC (and the Geneva Protocol) form the backbone of the norm against CW today, the international community has devised other instruments to support it. As has been the case since the late 19th century, security challenges evolve faster than the codification process.

The new tools tend to be action-oriented. They are the responsibility of individual states and implementation objectives are set against specific timelines. Other characteristics often include the informal nature of the arrangement, the formation of a coalition of like-minded states, and the absence of lengthy, formal negotiations to set the instruments up.

Another trend is the rising prominence of humanitarian and human rights law with the attendant focus on criminalising individual behaviour under international law.

The tools presented here are four of many initiatives launched or reinforced since the end of the Cold War.

Tools to reinforce the norm against Chemical Weapons

Australia Group

The Australia Group (AG) is an informal grouping of 42 states and the EU that aims to counter the spread of technologies and materials used for chemical and biological weapons through coordinated export controls, information sharing and outreach. It reviews its technology control lists at its annual meetings.

It was originally created in 1985 after the UN confirmed Iraq’s use of CW the year before.

UN Secretary-General’s Investigative Mechanism

The UN Secretary-General’s Investigative Mechanism (https://disarmament.unoda.org/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/ ) evolved from the investigations into Iraq’s violations of the Geneva Protocol between 1984 and 1988. Formalised by UN resolutions, it allows the UN Secretary-General (UNSG) to dispatch fact-finding missions at the request of a UN member.

When it comes to CW, the UNSG now draws on OPCW capacities and expertise to investigate alleged use by or in a non-CWC party. (The OPCW can launch its own investigations if a member state is involved.) For BW cases, the UNSG maintains a roster of national experts.

UNSC Resolution 1540 (2004)

After 9/11, the Security Council passed several anti-terrorism resolutions, including 1540, which aims to prevent terrorist acquisition of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. All UN members must adopt and enforce UNSC Resolution 1540 (https://disarmament.unoda.org/wmd/sc1540/ ), as well as report to the 1540 Committee on appropriate national legislation.

With regard to CW, the obligations parallel those of Article VII of the CWC, but apply to all UN members.

The 1998 Rome Statute and the ICC

The defines CW use as a war crime in both international and internal conflicts. The Hague-based International Criminal Court can pursue such violations if national courts are unwilling or unable to try criminals or after a UNSC referral.

The Rome Statute uses the language of the Geneva Protocol and does not refer to the CWC or BTWC, as some countries wished to avoid any reference to nuclear weapons