Chemical weapon basics

Chemical warfare is the intentional application for hostile purposes of toxic substances against humans and their environment. Toxic substances – poisons – interfere with life processes, thereby causing temporary or permanent damage to a living organism or killing it altogether. In warfare, humans are the primary target of armed action. However, besides anti-personnel chemical weapons, toxic warfare agents can also be directed against animals and plants.

Even though modern chemical warfare began in World War I (1914–1918) and the last of the chemical weapons declared under the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention were destroyed under the supervision of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in July 2023, the challenge of controlling the use of toxic chemical substances continues to this day.

This learning unit section introduces you to the nature of chemical weapons and the consequences of exposure to them.

What are chemical weapons?

Chemical weapons are any poisonous substances that are used deliberately to harm humans, animals or plants.

While other weapons may also have poisonous effects, toxicity is a secondary effect and not exploited for military purposes. In this sense, chemical weapons stand apart from

- smoke, which is used to obscure positions or mark targets;

- incendiary weapons, which are used to produce flame, mark targets or obscure view, or

- radiological weapons whose source of poisoning is radiation rather than a chemical reaction.

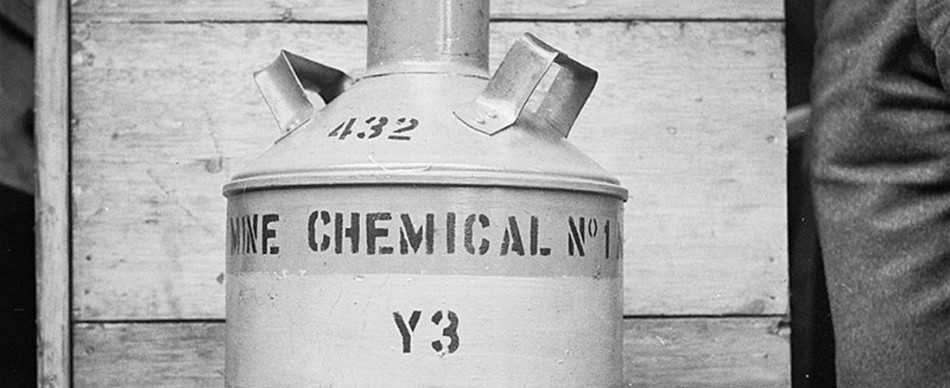

According to the definition set out in the Chemical Weapons Convention, a chemical weapon comprises three components. Besides the toxic agent, it also covers the means of delivery, such as a bomb or spray tank, and specialised equipment – e.g. to fill munitions with a chemical warfare agent. The convention treats any combination of these three components, as well as each component separately, as a chemical weapon.

The toxic agent

The toxic agent is the poisonous substance that may cause harm to living organisms. There is a wide range of toxic chemicals, both naturally occurring and synthesised in the laboratory.

Agents used for warfare purposes may be

- gases (e.g. chlorine);

- liquids (e.g. sarin or mustard agent); or

- solids (e.g. CS lachrymator).

However, not all toxic chemicals are suited for warfare. Warfare agents represent a compromise between different factors, including ease of production, long-term storage, stability after release and desired impact on the target.

Why not every toxic chemical makes a good chemical warfare agent

There are literally millions of highly toxic chemicals. Some potent ones even occur in nature and are mineral, animal or plant in origin. Some of the most poisonous substances known to humankind are toxins. Chemistry has added to the list of toxic substances, and the chemical industry is able to produce some of them in very large quantities. Today, chlorine, the agent used in the first major chemical attack in 1915, is produced in excess of 60 million tonnes a year. Moreover, research into new molecules results in the official registration of more than 170 million compounds each year. A considerable number of these will undoubtedly be highly poisonous, including substances that exceed the toxicity of the deadliest nerve agents by multiple orders of magnitude. Applying artificial intelligence (AI) to molecule design is likely to increase the number of new toxic compounds even further.

It may therefore appear remarkable that over the past 100 years, relatively few toxic chemicals were incorporated into the military arsenals and militaries around the world essentially selected similar types of agents. Variations in most cases were due to different methods of synthesis, manufacturing processes or the use of alternative precursor chemicals.

All major belligerents in World War I scanned many tens of thousands of potentially toxic compounds in the search for new and more effective chemical warfare agents. 1 However, since then only around 70 different chemicals were eventually used or stockpiled as warfare agents. An even lower number were standardised because a militarily useful agent actually represents a compromise between different demands:2

- A possessor country had to have sufficient production capacity to manufacture a particular agent in the required quantities and be able to manufacture different types of agent simultaneously.

- Lack of access to essential raw materials may limit the choice of warfare agents.

- A presumptive agent was not necessarily the most toxic available, but ‘suitably highly toxic’, so that it was not too difficult to handle during production, storage, transport, munition filling or destruction, or on the battlefield.

- The substance had to be capable of being stored in containers for long periods, without degradation and without corroding the packaging material.

- It had to be relatively resistant to atmospheric water and oxygen so as not to lose effect when dispersed.

- It also had to withstand the shearing forces created by the explosion, as well as heat when dispersed.

- Deployment of a particular warfare agent demanded availability of protection, medical care and pretreatment for one’s own troops.

Furthermore, a single chemical agent could not serve all battlefield purposes. The military had several types at their disposal and, depending on the mission, were able to select them on the basis of volatility versus persistency and lethality versus incapacitation.

The delivery system

Chemical warfare agents can be applied in several ways, including pouring the poisonous substance into a water container or delivery on the battlefield during an artillery barrage. However sophisticated or primitive the CW programme, a means to deliver an agent on the target will always be required.

The possibilities include:

- missile warheads and bombs;

- shells and grenades;

- aerosol generators and spray tanks.

But the technology may also be simple, including:

- precursor chemicals to a warfare agent rubbed on the victim (assassination of Kim Jong-nam, 2017);

- plastic bags (Aum Shinrikyo on the Tokyo underground, 1995);

- barrel bombs (Syrian civil war, 2013–2018);

- lorries filled with a toxic agent in suicide attacks (al-Qaeda in Iraq, 2006 and 2007, and ISIL in Syria, 2014–2015).

Specific equipment required to enable chemical warfare

While the toxic agent and the delivery system are the CW components that readily come to mind, different types of specifically designed equipment are needed in connection with the use of the munitions and devices mentioned above.

These may include:

- various types of installations to fill munitions with agent;

- tools to calibrate certain types of equipment;

- equipment for testing the agent quality.

Chemical weapons and other non-conventional weapons

A definition of chemical weapons suggests a clear and distinct arms category. In the case of the Chemical Weapons Convention, such sharp delineation is necessary to effectively implement the treaty provisions, especially those related to the verification regime. (The Chemical Weapons Convention will be discussed later in this learning unit.)

In reality, there are three main and distinct categories of non-conventional weapons but the boundaries between them are fuzzy.

The three distinct categories are as follows:

- Chemical weapons comprise toxic organic or inorganic molecules not usually found in nature. The toxic agents are the product of scientific research and industrial production (especially for warfare purposes) or laboratory synthesis (if smaller quantities are required).

- Biological weapons include self-replicating microbial organisms able to cause disease in humans, animals or plants. They occur naturally, but recent technological advances allow their genetic modification or synthetic design and production.

- Blast and heat are the principal destructive forces of nuclear weapons. However, they result from the energy released by fission or fusion reactions. Radiation is the third and least desired product of the nuclear reaction.

In between these three main categories, there are other types of weaponry combining characteristics, actions or effects of more than one main non-conventional weapon category:

Between biological and chemical weapons:

- Toxins are poisons produced by living organisms, including animals, plants and bacteria. Several of these are among the most toxic substances known to humans. Given their biological origin and poisonous action on humans, animals or plants, toxins are covered by both the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention.

- Bioactive molecules are subcellular particles that help regulate an organism’s life processes. They include proteins, peptides and prions. Research into bioactive molecules plays a key role in the development of novel central nervous system (CNS)-acting agents (previously referred to as ‘incapacitating agents’).

- Advances in nanobiotechnology and nanobioscience, too, hold the potential for future synthetically developed agents that blur the distinction between biological and chemical agents.

Between chemical and nuclear weapons:

- Radiation poisons living organisms. Radiological weapons or other dispersal devices specifically seek to exploit this characteristic. However, the poisoning is not the result of the agent’s direct toxic action, as is the case with CW.

- Incendiary agents produce extreme heat and are able to set many materials alight, including metals and steel. The heat is the consequence of a chemical reaction, but its effect on living organisms is not a consequence of the agent’s direct toxic action, as is the case with CW.

Between chemical and incendiary weapons:

- In the past, favourable winds steered smoke from toxic candles to enemy lines or poisonous smoke could force defenders to abandon enclosed positions. Some incendiary weapons, such as white phosphorus, are used to generate smokescreens. In high concentrations (e.g. in enclosed positions), the smoke may prove sufficiently toxic to harm humans or animals. Exploiting toxicity is not the customary purpose for using incendiary weapons.

Contrary to chemical and biological weapons, the use of nuclear or radiological weapons is not explicitly prohibited. Incendiary weapon use is regulated under international humanitarian law, notably Protocol III of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons.

Classification of chemical warfare agents

There are many different ways of classifying chemical warfare agents. The most common method is based on the physiological consequences of exposure. Here, we can distinguish between six major CW categories: choking agents, blood agents, blister agents, nerve agents, central nervous system-acting agents, harassing agents and anti-plant agents. (Some agents may produce symptoms characteristic of more than one category.)

Choking agents injure the respiratory tract, flood the lungs with fluids and consequently impede breathing.

- Examples: chlorine, chloropicrin, phosgene Blood agents prevent the exchange of oxygen between the lungs and the red blood cells, and hence the transportation of oxygen to the different parts of the body.

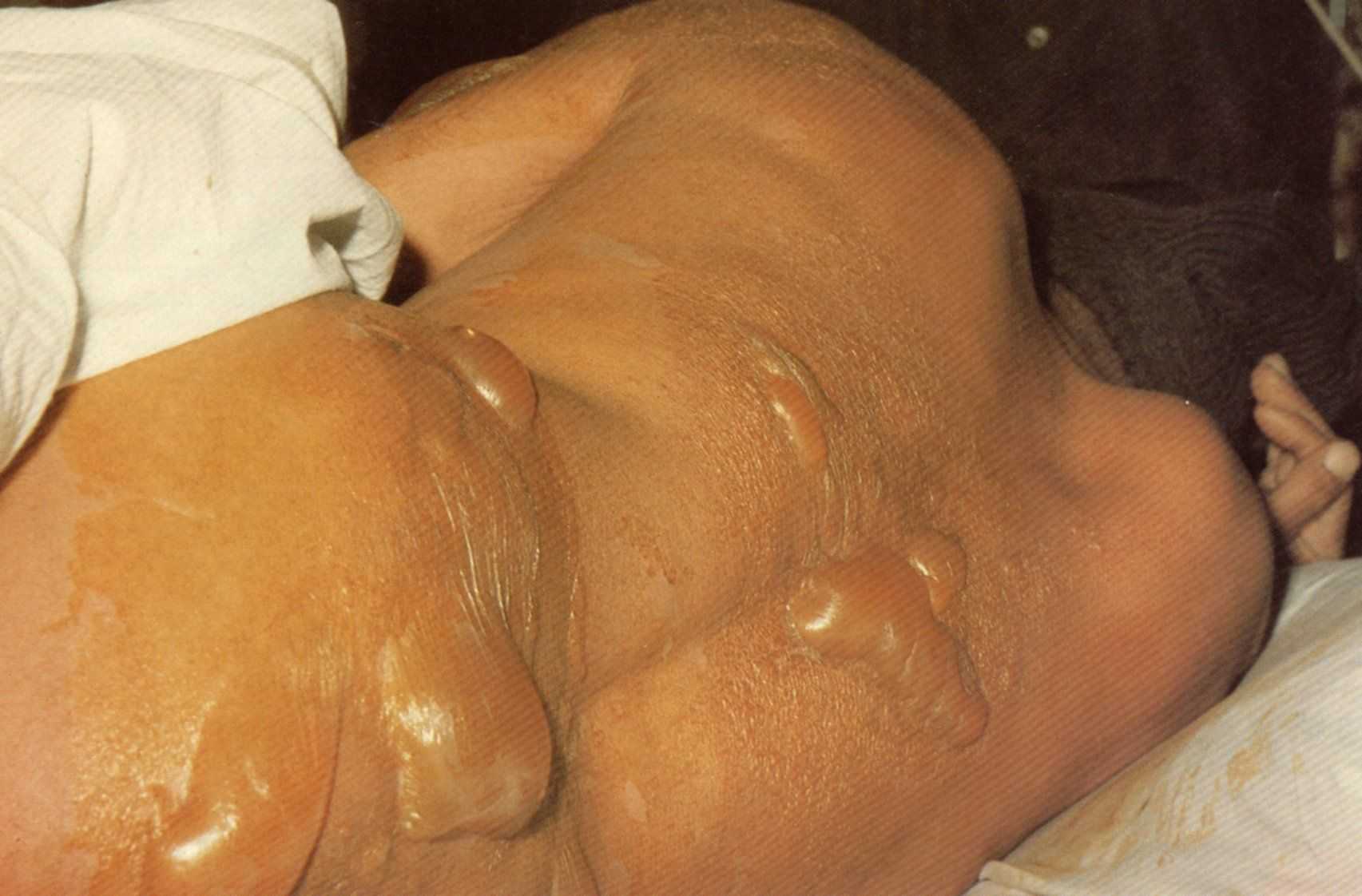

- Examples: hydrogen cyanide, cyanogen chloride, phosgene The various mustard agents are blister agents or vesicants. Besides affecting the respiratory tract if inhaled, blister agents attack the skin. Some other agents may also cause blistering or severe rashes and may, therefore, be listed as blister agents.

-

- Examples: nitrogen mustard, sulphur mustard, lewisite

-

- Occasionally listed as a blister agent: phosgene oxime

Trigger warning! The photo on the next tab shows the unpixelated image of a person affected by mustard agent exposure, with large blisters visible on the skin.

Nerve agents

were first discovered in the late 1930s while researching new insecticides. They attack the central nervous system. They can kill rapidly as their toxic action on the central nervous system interferes with the functioning of organs and the coordination between those organs.

- Examples: tabun, sarin, soman, VX, and novichok agents

Trigger warning! The photo on the next tab shows the unpixelated image of this dead young victim to nerve agents.

Whereas the toxic chemicals in the four categories above are also known as lethal agents, those in the following categories are often viewed as non-lethal (although they too can kill if the dose is high enough or a person is exposed for a long time).

Harassing agents produce strong sensory irritation, but their effects disappear soon after an exposed person is evacuated from the affected area.

Examples:

- Lacrymatory (riot control) agents: chloropicrin, CN, CS, oleoresin capsicum (pepper spray)

- Malodorant agents: skunk, stink bombs

- Sternutator (sneezing) agents: diphenylchloroarsine (DA, Clark I), diphenylcyanarsine (DC, Clark II), phenyldichloroarsine (Pfiffikus, phenyl Dick)

- Vomiting agents: adamsite (DM), chloropicrin

Central nervous system (CNS)-acting agents also have temporary effects on victims, but these last considerably longer – sometimes for hours or days – after exposure. They interfere with the functions of the central nervous system, causing a person to become uncoordinated and consequently incapable of coherent actions.

Examples: BZ, fentanyl, LSD

Anti-plant agents also come in different forms, such as defoliants, growth inhibitors or herbicides. Their primary purpose is to damage the enemy’s ability to grow food. They have also been used to defoliate forests in tropical regions, such as in the Vietnam War in the 1960s, so that enemy troop movements can no longer benefit from the cover offered by the trees.

Examples: Agent Orange, Agent White

.jpg)