Military Objectives of Chemical Warfare

Major Chemical Warfare Incidents Before 1945

Modern began on 22 April 1915 with the release by German Imperial troops of a massive chlorine cloud near Ypres, Belgium. As the war progressed, competition between increasingly lethal agents and improvements in chemical defence intensified. By late 1918, a total of 50 percent of all shells fired were chemical. The Armistice also ended chemical warfare in Europe, which had killed many tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians and injured possibly up to a million people. Toxic agents scarred many survivors for life, for instance, through blindness or damaged lungs.

Expectations were that if the war had continued into 1919,use would have surpassed that of conventional munitions. A new type of agent, lewisite, was on board transport ships en route from the USA to Europe when the arms fell silent.

The fear of did not disappear, however. World War I had been a war of innovation, with aeroplanes in particular becoming part of future threat scenarios. It was feared that bombers armed with CW could annihilate whole cities. Politicians, peace campaigners, humanitarian organisations, etc., painted apocalyptic pictures of the end of humanity, not unlike current views of nuclear warfare. In Europe, a balance of terror combined with national civil defence preparations were among several factors that contributed to the prevention of gas warfare in World War II.

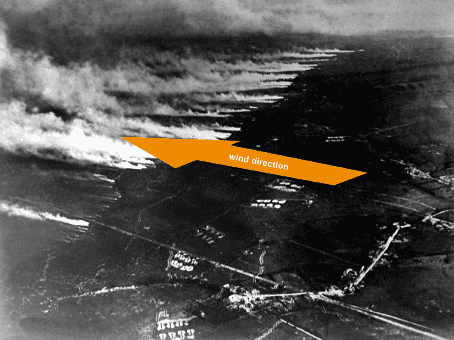

While the shock of chemical warfare certainly had an effect in Europe, other parts of the world were hit even harder, as the same countries that had suffered from chemical weapons during World War I used them in their colonial wars. Between 1921 and 1927, Spain and France deployed various chemical warfare agents against the Berber rebels during the Rif war. It was the first use of modern CW in a colonial war. After this, Italy resorted to CW in its colonial campaign against Ethiopian troops between October 1935 and May 1936. And Japan experimented with toxic chemical agents and used them extensively during the battle of Changde (November–December 1943) during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).

- 1914–1918

World War I: generalised CW use from April 1915 onwards

- 1919

British use of airdropped DM bombs in North Russia

- 1921

Soviet CW use during the Tambov uprising

- 1921–1927

Spain and France launch several CW attacks to suppress the Berber uprising in the Rif, Morocco

- 1928

Italy drops mustard bombs during the colonisation campaign in Libya

- 1934

Following their invasion of Xinjiang, the Soviets airdrop mustard agent bombs forcing the Chinese defenders of Dawan Cheng to retreat

- 1935–1939

Repeated Italian use of mustard bombs during the campaign in Abyssinia (Ethiopia)

- 1937–1939

Japanese troops use various types of CW during the campaigns in China

- 1939–1945

World War II: sporadic CW incidents reported. With the exception of Japanese use in a few campaigns, CW does not appear to have been part of the belligerents’ military strategies.

Major CW incidents after 1945

World War II ended without sustained chemical warfare campaigns. The atomic bomb became the symbol of both military prowess and existential fear. Chemical weapons disappeared into the background but retained relevance for intra-war deterrence. The discovery of highly lethal and fast-acting nerve agents in the 1930s drove post-war preparations. However, there were still several instances where chemicals were actually used in warfare.

During the 1960s, the USA progressively intensified the spraying of herbicides and defoliants over Vietnam and neighbouring countries to deny North Vietnamese forces and insurgents jungle cover. Chemicals such as Agent Orange permanently destroyed large parts of the vegetation and are still cause illness and birth defects among the local population and US veterans to this day. These were the first indications that exposure to chemical weapons could have transgenerational effects because of genetic damage transmitted to from the original victims to their descendants.

Between 1962 and 1970 several allegations were made that Egypt resorted to during its intervention against royalist forces in the civil war in Yemen. Some 40 incidents were reported.

During the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), Iraq initiated, in 1982 or possibly earlier, the most extensive use of CW since World War I. From late 1983 on, CW became a regular feature and, in the final two years, Iraq systematised their use against Kurdish insurgents and civilians. Iran is not believed to have resorted to CW.

In 1987, Iraq introduced CW as a means of genocide against the Kurds. After the ceasefire with Iran on 20 August 1988, operations against the Kurds continued into the following month.

In 2013, two years into the Syrian civil war, there were increased reports of CW use, culminating in the sarin attack against Ghouta in August. Since joining the in October 2013, attacks with chlorine continued to be carried out by both government forces and ISIL. Syria seemed to have ceased its chemical attacks after April 2018.

Up to the end of the Cold War, the USA and USSR built up and modernised arsenals comprising many tens of thousands of tonnes of warfare agents. However, except for the Vietnam War, all major chemical warfare has occurred and remains a significant threat in the Middle East. It is a historical fact and psychological factor that has been largely overlooked in the efforts to free the region from non-conventional weaponry.

- 1948–1960

Malaya war

British forces spray herbicides and defoliants to deny the insurgents forest cover

- 1962–1970

Yemen civil war

Egypt resorts to CW on several occasions

- 1964–1979

Rhodesian War of Liberation

the White minority government contaminates clothing, food and beverages with organophosphate pesticides and rodenticides

- 1980–1988

Iran–Iraq War

generalised CW use by Iraq from 1983 onwards, including the first-ever release of nerve agents in combat. The Iraqi forces also deploy CW against the Iraqi Kurdish insurgents and population centres, including Halabja (March 1988)

- 2003–2011

The al-Anbar Awakening

al-Qaeda in Iraq conducts a series of suicide bombings using lorries filled with liquid chlorine against the local Arab population and US forces in 2006–2007

- 2011–present

Syrian civil war

frequent use of vesicants, nerve agents and chlorine from 2013 on. Chemical warfare appears to have ceased in April 2018. The Islamic State also uses CW on a few occasions

- 2014–present

Russo-Ukrainian War

there are repeated allegations of Russian use of lachrymatory grenades, which have increased since late 2023

Terrorism with chemical weapons

After the end of the Cold War, concerns about catastrophic, mass casualty terrorism grew rapidly. Aum Shinrikyo’s release of sarin on the Tokyo underground in March 1995 seemed to confirm the worst fears. After the 9/11 attacks on the USA, the fear escalated even further. Following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) used lorries filled with chlorine in a series of suicide attacks. During the Syrian civil war, the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which evolved out of AQI, resorted to chemical weapons as a method of warfare – a novelty for a terrorist entity.

Until today, the projected mass casualty scenarios have not materialised. Acquisition of warfare agents has proven more complex than the availability of technologies and skills might suggest, not least because of the need for functional specialisation and the weapon programme’s impact on internal group dynamics. Today, greater transfer controls and law enforcement awareness have raised additional barriers.

Most incidents with toxicants are criminal in nature, including revenge attacks by individuals using commercial or off-the-shelf chemicals.

The complexity of terrorist acquisition of chemical warfare agents

In the ‘toxic agent’ section above, it was noted that throughout the history of modern chemical warfare, the number of toxic chemicals selected and standardised for chemical warfare was very low relative to the number of known poisonous compounds. This was the consequence of two sets of factors:

-

Any chemical warfare agent represented a compromise between various factors (e.g. ease of production, storage without degradation, physical properties after release, etc.)

-

The mission-oriented selection of particular warfare agents (e.g. degree of volatility or lethality), in other words, the choice of a chemical warfare agent that best meets specific operational goals at a given point in time.

Terrorist entities cannot escape these factors once they decide to develop a chemical weapon capacity. They, too, need to balance their operational desires against the available scientific and technical skills and the production capacity they would be able to establish (e.g. laboratory, pilot plant or factory-level volumes). New elements will enter the equation as the programme scales up. Thus, for example, if a grouping limits its ambition – and therefore the demand on various skills and expertise – to laboratory synthesis of a single agent, then it will not have to invest resources in seeking technologies to stabilise the agent for long-term storage, which would be a requirement if the terrorist entity had opted for large-volume manufacture. While it is true that a terrorist entity can easily gain access to literature describing the chemical reactions, the processes require testing and fine-tuning at each and every level of the acquisition process. Different scales of activity also place different demands on the available skill sets. Thus, while the chemists in the Japanese religious cult Aum Shinrikyo managed to produce high-quality sarin in the laboratory, these individuals lacked the chemical engineering expertise needed for setting up and operating a pilot plant. Aum Shinrikyo never managed to get its factory up and running.

Whereas a state-run programme can research toxic chemicals, develop production methodologies and store stockpiles over decades, the luxury of time is something a terrorist entity never has. Moreover, contrary to a state, a terrorist grouping does not enjoy freedom from prosecution. A state can operate a secret programme hidden somewhere on its territory and no other government or authority has jurisdiction over the activities conducted within that state’s borders. A terrorist organisation, in contrast, operates on the territory of a country and government authorities are likely to have adopted and implemented a variety of legislative and criminal measures to counter the terrorist threat. The fear of raids on facilities is a major factor in terrorist decision-making. However, these counterterrorism measures also affect the grouping’s access to key raw materials, equipment and expertise, as various types of internal and international technology transfer controls inevitably create obstacles to setting up a secret chemical weapon programme within the borders of a given country.

The larger a chemical weapon programme becomes and the more people become involved, the greater the risks of breaches of secrecy or detection. Front operations need to be set up to provide a legitimate cover for acquiring certain types of chemical precursors or specialised equipment. Accidents may happen. Despite brainwashing, individuals working in the programme may start having misgivings or inadvertently divulge information about activities. Agents need to be field tested for their effectiveness and behaviour under realistic conditions. Large-volume production implies safe and secure storage facilities, which widen the footprint of the chemical weapon programme enormously.

While a terrorist organisation may opt to move its chemical weapon programme to the territory of a failed state or a state with poor internal controls, this decision creates different types of obstacles. Transport of sizeable agent volumes from the production location to the site of attack results in fresh logistical demands, which are informed by factors such as agent stability, transport opportunities, handler safety, secrecy and the need for enhanced intelligence about the target and local preparations, among many others.1

A large chemical weapon programme would involve significant changes to the weapons acquisition process (indigenous production with growing risks of detection versus theft of weapons or black market purchases), lead to a reframing of the long-term strategic goals and identification of the specific roles of (and thus benefits from) chemical weapons, a shift of emphasis in the selection of primary targets, training and physical protection of group members, and the development of new security and safety procedures, all the while bearing in mind that sizeable chemical weapon production or storage would affect mobility and furtiveness. These changes can also be expected to have knock-on effects on the grouping’s organisational structure (e.g. to accommodate production and storage) and leadership organisation (e.g. placing scientific and technical experts in positions of authority and addressing internal rivalries resulting from their views on ideological questions or operational planning). In addition, they would have to acquire operational knowledge of technology purchasing or black market practices in unfamiliar settings.

Despite many scenarios and simulations of catastrophic terrorism with chemical warfare agents, the projections have not played out in reality. Aum Shinrikyo’s programme failed in all respects relative to the goals the group had set itself, namely taking over the Japanese government. The two sarin attacks in Matsumoto (1994) and Tokyo (1995) resulted in some fatalities and many other wounded, but the two incidents were indicative of failing strategic ambitions and the actions did not even achieve their immediate tactical objectives. Admittedly, several individuals and some organisations have since displayed interest in toxic substances, and in both Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has mounted attacks with chlorine-filled munitions and used mustard agents on a few occasions. However, on the whole, terrorist entities have shown little interest in warfare agents. The main explanation may be that terrorists have different goals than the military. Therefore, the question arises as to why the compromises that drove the selection of military agents should apply to them. If their purpose is to terrorise, then smaller volumes or different types of toxic chemicals – particularly ones that have fewer requirements in terms of access to materials and equipment, skill levels and organisational structure, and hence reduce risk of discovery – may serve their goals.

Thus, in several cases, we may observe groups or individuals acquiring or attempting to acquire small quantities of highly poisonous substances – in most instances, plant toxins, such as abrin or ricin, or commercially available toxicants, such as rat poison or acids. In other instances, a terrorist entity may resort to the opportunistic use of industrial toxicants. The former case typifies the so-called “lone wolf” terrorists, on the one hand, and individuals or activist groupings bearing a grudge against another individual, a company or organisation, or a specific section of society, on the other hand. The latter case occurs most often in wars or insurgencies when one of the parties draws on stocks in storage sites or chemical plants. The resort to chlorine manufactured and stored for water purification in the Syrian civil war and in Iraq is a typical example. Industrial toxic chemicals have also been deliberately released or threatened to be released into the environment to force government officials or company directors to accede to demands by protestors or domestic radicals.2

Catastrophic scenarios involving mass human casualties from terrorism with toxic agents are highly unlikely. Moreover, societies can take several measures to prevent such incidents or mitigate the worst consequences should they occur. Domestic legislation and regulations and their effective implementation, together with lawful law enforcement techniques, can disrupt the pursuit of chemical weapons before a terrorist entity or individuals come close to achieving such capacity. This is the responsibility of all states under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) or UN Security Council resolution 1540 (2004). Furthermore, the development and implementation of chemical safety and security measures for production plants and storage facilities, as currently being promoted by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), reduce the possibility of opportunistic use of industrial toxic chemicals by terrorists, radicals or protestors, while advancing a culture of responsibility among scientists and professionals.

Aum Shinrikyo’s high-tech apocalypticism

The Japanese cult created an apocalyptic religious doctrine that required it to develop advanced weaponry to battle and survive the forces of evil. Its doctrine incorporated many science fiction elements, which was part of the group’s attraction for disaffected science and technology students and professionals.

Aum Shinrikyo set up several weapon programmes, one of which involved the production of 80 tonnes of sarin to help trigger Armageddon. It developed sarin in the laboratory and set up a production unit, which failed. However, the leadership of the cult became extremely paranoid about discovery as the project progressed. It also came into increasing conflict with Japanese society and the internal pressure to use the sarin to demonstrate its power before achieving full capacity grew.

In June 1984, it created a sarin vapour to try and kill three judges set to rule in a land dispute in the town of Matsumoto; in March 1995, it released sarin in metro trains in Tokyo with the aim of preventing police raids on cult compounds. Eight people lost their lives in Masumoto and many more suffered the effects of exposure to the sarin. In Tokyo, 13 people were killed, hundreds more injured and several thousands of communters suffered severe psychological trauma. Still, these attacks were a far cry from the cult’s original goal to replace the government of Japan, and in fact the CW programme eventually led to Aum Shinrikyo’s demise.

ISIL’s opportunistic use of industrial toxicants

In 2006–2007, al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) launched a series of chlorine truck bomb attacks against local Iraqi and US forces. The chlorine killed no one. Al-Qaeda in Iraq intercepted lorries transporting liquid chlorine from Jordan and Syria intended for water purification in Baghdad.

Al-Qaeda in Iraq became the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In Syria, the group began experimenting with chlorine-filled mortar grenades, which in 2015 became more of a method of warfare than terrorism. It then expanded the practice in its operations against Kurds in Iraq. The also confirmed cases of ISIL using mustard agent in Syria and Iraq.

Footnotes

-

See, Zanders, Jean Pascal (2016): Internal dynamics of a terrorist entity acquiring biological and chemical weapons. In: Brecht Volders and Tom Sauer (eds.), Nuclear Terrorism: Countering the Threat. Routledge: Abingdon, 26-54. ↩

-

Zanders, Jean Pascal/Karlsson, Edvard /Melin, Lena /Näslund, Erik/Thaning, Lennart. 2000. “Risk assessment of terrorism with chemical and biological weapons”, in: SIPRI Yearbook 2000. Oxford University Press, 537–59; Zanders, Jean Pascal. 2014. “Chlorine: A weapon of last resort for ISIL?”, in: The Trench (blog), 27 October 2014, available at: http://www.the-trench.org/chlorine-isil/) and “‘Chlorine: A weapon of last resort for ISIL? (Part 2)”, in: The Trench (blog), 18 February 2015, available at: http://www.the-trench.org/chlorine-isil-2/469. ↩