The international community has drawn clear red lines about the misuse of biology. The two biological cornerstones of the rules of war are the and the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC). Together, they prohibit the development, production, stockpiling and use of biological weapons.

The 1925 Geneva Protocol

Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare

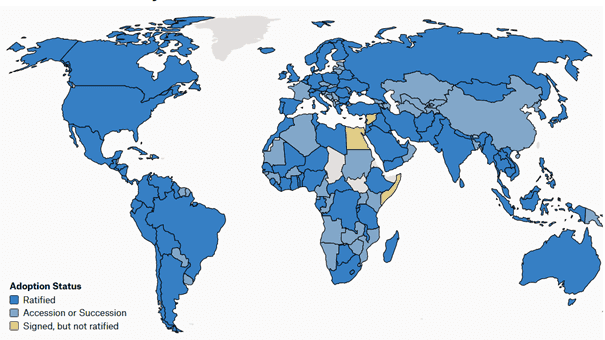

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, commonly known as the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in war.

Current Adoption

Data: UNODA Treaties Database

Prompted by the horrific experiences of chemical warfare during World War I, the 1925 Geneva Protocol (official name: Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare) was negotiated under the auspices of the League of Nations from 4 May to 17 June 1925. The aim was to prevent similar atrocities in future conflicts. It entered into force on 8 February 1928 and has the status of an international treaty that prohibits the use of biological and chemical weapons in war. Over time, many countries have joined the Protocol, reinforcing the global norm against the use of such weapons.

Adoption Status

Map showing member states of the Geneva Protocol

Data: Natual Earth. Graphic: PRIF

However, it does not explicitly prohibit their development, production or stockpiling. As a result, the Protocol contained considerable loopholes enabling states to legally possess and manufacture biological weapons ‘just in case’. Over time, an increasing number of states felt that the Geneva Protocol was inadequate and that the loopholes had to be closed, eventually leading to the Biological Weapons Convention.

Biological arms control and disarmament: The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)

Today, the cornerstone of the biological arms control and disarmament regime is the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), or the ‘Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction’, as it is officially known.

- 1968

Negotiations begin

- 1969

Nixon’s elections opens a window of opportunity

- 1972

Opened for signature

- 1975

Entry into force

- 1980

First review conference; Swedish proposal for Consultative Committee fails

- 1994–2001

Negotiations on compliance protocol also fail

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) is a treaty that prohibits the development, production, and stockpiling of biological and toxin weapons.

Current Adoption

Data: UNODA Treaties Database

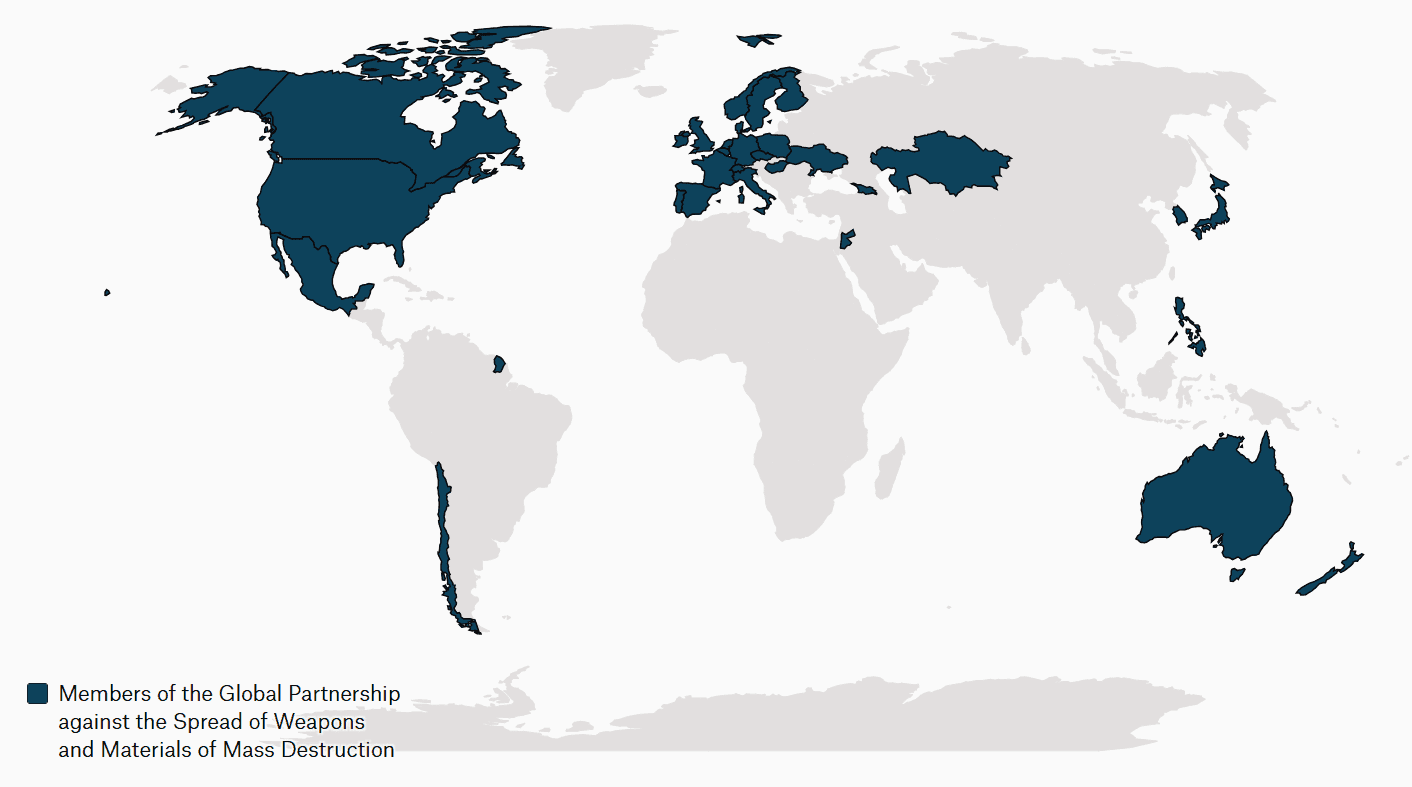

Cooperative Threat Reduction

The Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Programme was established by the United States to provide former states of the USSR with assistance to destroy their unconventional weapons. The creation of the CTR Programme in 1991 was a historically rare innovation in international problem-solving

Prior to the early 1990s, states accomplished the reduction of arms through laboriously negotiated treaties such as the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty or the 1990 Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty. Or they withdrew weapons unilaterally – usually in tandem with the introduction of improved versions of the weapons being retired.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union left several of the 15 successor states with major nuclear, chemical and biological weapons capabilities.However, they had limited resources to deal with these capabilities. The Cooperative Threat Reduction Programme was established by the US to provide these states with the necessary assistance to destroy their unconventional weapons, to ensure the security and safety of the weapons in storage, and to put verifiable safeguards in place against the proliferation of such weapons.

However, they had limited resources to deal with these capabilities. The Cooperative Threat Reduction Programme was established by the US to provide these states with the necessary assistance to destroy their unconventional weapons, to ensure the security and safety of the weapons in storage, and to put verifiable safeguards in place against the proliferation of such weapons.

The original focus of the CTR Programme was primarily to help Russia and the other former Soviet Union states meet their obligations under various arms control treaties. The Biological Weapons Convention prohibits biological weapons, but permits research to develop vaccines and therapeutics such as antibiotics.

Yet, the treaty offers little specific guidance about when such research, testing and other biological activities crosses over into the military realm. Since the BWC lacked the kind of concrete destroy-this/reduce-that/definitely-do-‘x’ definitions that you find in the nuclear accords, the biological mission for the CTR Programme was not as easily defined or executed in the early 1990s.

A big impetus for the biological CTR work was to enhance transparency and to get Moscow to open up about its bioweapons programme. The Russians did not see a downside to having CTR assistance at the Biopreparat facilities, but Ministry of Defence officials drew a red line and refused Western requests to visit the military biological facilities. The Ministry of Defence also blocked collaborative research grants to military scientists.

Despite this, biological CTR programming in the former Soviet Union was very successful. It upgraded the physical security of a number of facilities and trained staff in more rigorous safety and security practices. It enabled the destruction of Steponogorsk, the main BW production facility in the Soviet Union, and cleaned up much of the BW test site in the Aral Sea so that it posed less of a health threat to local populations, both human and animal – and, of course, the clean-up also limited access to potential BW agents. ‘Brain drain prevention’ grants, provided as part of CTR programming through the International Science and Technology Center, kept a lot of bioweaponeers in Russia in gainful employment so they did not have to look for other employers who might have exploited their expertise or access to various genetically engineered pathogens. The European Union and other Western states began adding funds and projects to the US CTR initiative. This was formalised in 2002 through the Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction.

When the CTR Programme started, the funds available to tackle nuclear and chemical weapons threats far outstripped those to address the biological threat. Now, biological programmes are the largest part of the overall CTR budget, and the focus is on providing states with the capabilities to manage a disease outbreak, regardless of whether it is naturally occurring or deliberately introduced.