EU regulations on SALW exports

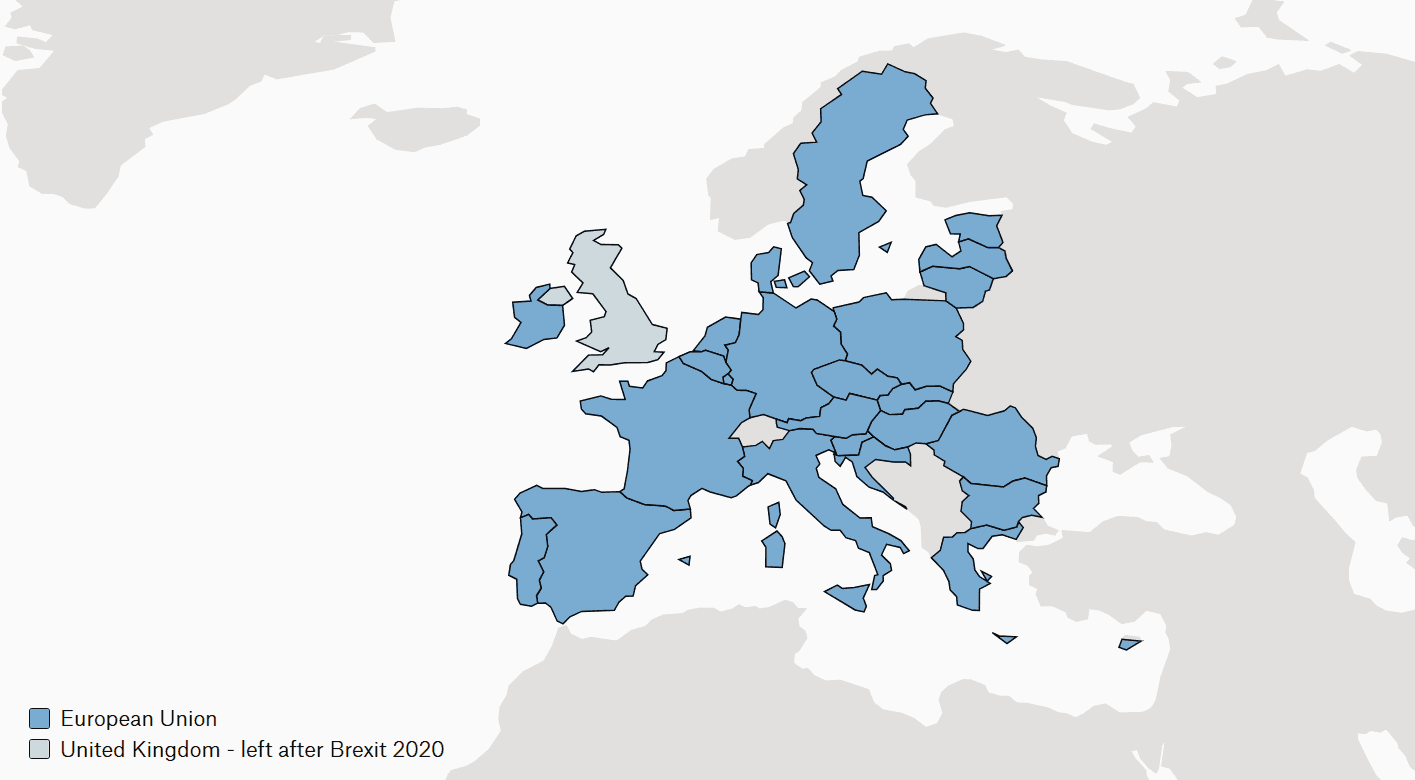

The EU is an important producer and exporter of SALW. European Union reporting does not allow clear identification of the licensed and effective export of small arms and light weapons, only the export of firearms. Based on the available data, we can conclude that:

- the value of licensed exports of firearms by EU member states exceeded 3.6 billion euros and the value of effective exports exceeded 500,000 euros in 2022;

- more than half of these exports were destined for North America;

- the major EU exporting countries in 2022 were Austria, Latvia, Croatia, Germany, Belgium, Bulgaria and Italy.

Fact sheet: Common Position 2008/944/CFSP on arms exports

The Common Position was adopted in 2008 by all EU member states under the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy according to article 29 of the Treaty of the European Union.

Member states are obliged to ensure that their national policies conform to the Union positions.

The Common Position sets out common minimum standards for arms export control by EU member states. It also applies to brokering, transit transactions and intangible transfers of technology. Member states may adopt more restrictive legislation.

The provisions of the Common Position apply to goods listed in the EU Common Military List. This list acts as a reference point for member states’ national lists (without replacing them). The EU Common Military List comprises 22 categories. Small arms and light weapons are also included in this list but in a separate category.

Common Position assessment criteria

- Respect for member states’ international obligations and commitments

- Respect for human rights and international humanitarian law

- Internal situation in the country of final destination

- Preservation of regional peace, security and stability

- Security of member states, as well as that of friendly and allied countries

- Behaviour of the buyer country with regard to the international community

- Existence of a risk of diversion or undesirable re-export

- Technical and economic capacity of recipient country

Additional provisions

- Export licences shall only be granted on the basis of reliable prior knowledge of end use in the country of final destination.

- Member states are required to exchange information on denied export licenses and to consult each other before approving a license that has been denied by another member state.

- Member states are required to publish an annual report of their arms exports and circulate it to the other member states.

- The document foresees the drafting of an annual report on the exports of military items by all EU member states. Member states shall publish national reports on their exports and report to the EU.

A user’s guide was developed in 2003 to assist member states in implementing the Common Position

Regulation of firearms possession and transfers within the EU

Since the early 1990s, the EU has defined minimum common rules on the acquisition, possession and transfer of civilian firearms within the EU. In 1991, the first EU Firearms Directive was introduced. Following amendments made in 2008 and 2017, the EU adopted a new Directive on control and possession of weapons (Directive 2021/555) in 2021.

Like its predecessors, EU Firearms Directive 2021/2555 is a legally binding instrument that is not directly applicable, but needs to be implemented through national legislation. Importantly, this Directive only introduces minimum standards. This means that member states may adopt more stringent legislation.

A crucial element of the Firearms Directive is the establishment of three categories of firearms.

Category A firearms, such as automatic firearms, are prohibited firearms. The acquisition and possession of these firearms is not allowed. There are, however, some exceptions. For example, the Directive stipulates that member states can choose to grant to museums and collectors, under strict security conditions, authorisations to acquire and possess such firearms, their essential components and ammunition. Dealers and brokers, in their respective professional capacities, are also allowed to acquire, possess and transfer such firearms.

Category B firearms, including most semi-automatic short firearms, such as pistols and revolvers, are subject to authorisation. The acquisition and possession of firearms that fall under this category are only allowed when a person is at least 18 years of age, has a so-called “good cause” (for example target shooting or hunting) and does not present a danger to themselves, to public order or to public safety.

Category C firearms, such as long firearms with single-shot rifled barrels, are subject to declaration only.

The Firearms Directive also includes various additional requirements such as provisions on the authorisation of arms dealers, the marking and registration of firearms, the conditions for transfers to other EU member states, and information exchange between member states.

EU policy on illicit trafficking of SALW

In addition to the development of a regulatory framework for the legal possession and transfer of civilian firearms and for the authorised export of small arms and light weapons, the EU has also translated the international focus on the illicit manufacturing and trafficking of these weapons into EU policy. In 2005, the EU adopted its “strategy to combat illicit accumulation and trafficking of small arms and light weapons and their ammunition” as part of a wider European Security Strategy. Until then, EU actions on disarmament were mainly reactive and focused on disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programmes and on security sector reform in post-conflict countries. From 2005 on, however, this reactive approach has been supplemented by preventive action aimed at tackling the illegal supply and demand as well as controls on exports of conventional weapons. Particular attention was given to the problem of arms transfers to sub-Saharan Africa and the huge stockpiles of small arms and light weapons in Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

Fact sheet: The EU strategy against illicit firearms and SALW (2018)

- It is intended to be a comprehensive plan of action to combat the illicit trade in firearms, SALW and their ammunition and contains various measures to secure the full life cycle of these weapons.

- It takes into account the changing security environment and has a double objective:

- to guide integrated, collective and coordinated European action on this security threat and

- to promote accountability and responsibility with regard to the legal SALW trade.

Key aspects of the 2018 EU strategy:

- Strengthening the normative framework by supporting a multilateral approach to arms control and non-proliferation efforts such as the ATT, UN Firearms Protocol and the UN Programme of Action on SALW

- Implementation of norms in the different life cycle phases of firearms and SALW by strengthening controls on the manufacturing and export of these weapons and by improving the stockpile management and responsible disposal of these weapons

- Compliance though monitoring SALW flows in conflict-affected areas and improving information sharing and operational law enforcement cooperation within the EU

- Strengthening international and regional cooperation and assistance, with a particular focus on the regions likely to pose a threat to the EU’s security and most likely to benefit from EU action

In recent years there has been growing concern regarding the illicit trafficking of firearms within the EU and the threat these weapons represent to the security of EU citizens. Recent terrorist attacks and criminal acts using illegal arms are currently partially shifting the focus from illicit use and transfers of these weapons outside the EU borders to illicit flows to and within the European Union.

In 2020, the European Commission adopted a new “action plan on firearms trafficking”. This action plan contains four major priorities. The first priority is to safeguard the licit market and limit diversion of firearms from the licit to the illicit market, for example by following up on the correct transposition of the EU Firearms Directive by the member states and by analysing how to best address emerging and future threats such as 3D printing of firearms. The second priority is to build a better intelligence picture of firearms trafficking into and within the EU, for example by taking actions to establish a systematic and harmonised collection of data on firearms seizures across the EU and by exploring the feasibility of rolling out a tool to track firearms-related incidents in real time. The third priority is to increase pressure on criminal firearm markets, for example by urging the member states to establish fully staffed and trained Firearms Focal Points within their borders and by improving cooperation between law enforcement and parcel and postal operators to ensure stricter oversight of shipments containing firearms or their components. The final priority is to step up international cooperation, especially with countries in Southeast Asia and the Western Balkans, as well as Ukraine and Moldova, but also with countries in the Middle East and North Africa.