The History of the Idea of a Nuclear Weapon free zone in the Middle East

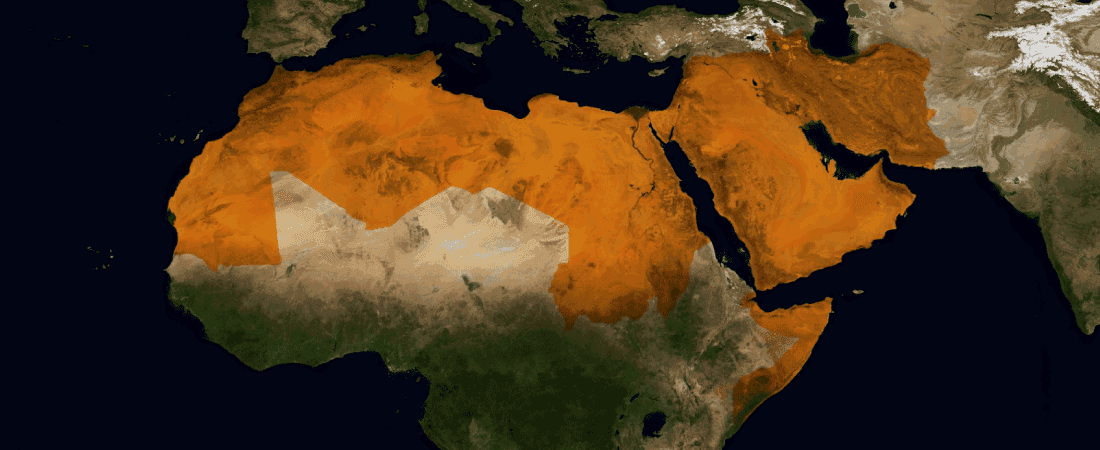

The Middle East, the term coined by the European colonizers to denote the territory neighbouring Europe in the south, has never been defined properly. For the purpose of the zone, the Middle East was originally delineated as the territory from Libya in the west to Iran in the east, from Syria in the north and Yemen in the south, but was later expanded to include all Arab League member states, plus Iran and Israel. Although there were suggestions to include Afghanistan, Pakistan and Turkey, for the purpose of the NWFZ/WMDFZ these have been left outside the official concept of the region.

The Middle East NWFZ was first proposed in 1974 by Iran and Egypt. However, the complex security situation in the Middle East made the establishment of such a zone impossible to this day. While for several decades it was the Arab/Palestinian-Israeli conflict that was the main obstacle, in the 2000s this has been complemented by the Israel-Iran nuclear controversy. Besides the lack of formal peace between the Arab states and Israel, the other striking feature of the conflict was the asymmetry in capabilities: Israel is believed to have a nuclear arsenal as well as a chemical and a biological weapons programme. Some – but not all – Arab states have had chemical and biological weapons capability. In realization of this asymmetry Egyptian President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak in 1990 proposed to expand the NWFZ into a zone free of all weapons of mass destruction (WMDFZ), which was referred to in UNSC Resolution 687 (1991) and then set as an aim by the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference. In spite of the fact that the 1995 Resolution on the Middle East calls on the states of the region to join the NPT in a general way only, it has become the main point of reference for any future initiative. Although neither the 2000 nor the 2005 NPT Review Conferences led to a breakthrough, it was the 2010 NPT Review Conference that set five “practical steps” towards the realization of the Middle East zone. It was agreed that a conference on the zone should be organized in 2012.1

However, due to the political events of the year (most of all the presidential campaign and elections in the US) and the differences of opinion by some regional states (first of all Israel and Iran), the conference on the Middle East NWFZ/WMDFZ had to be indefinitely postponed. The lack of progress on the Middle East zone was expected by many to threaten the outcome of the 2015 NPT Review Conference as well. At the 2015 Review Conference Egypt supported by the Arab League put forward a new proposal in which the UN Secretary General would be the sole authority in charge of convening the conference on the Middle East zone, transferring the issue from the NPT framework to the UN. This way Israel would also be included, and the original sponsors, first of all the US, would lose their responsibility in the setting of the agenda and convening the conference. The proposal also included the establishment of two working groups, one for scope, geographic demarcation, prohibitions and interim measures, and one for verification and implementation mechanisms. The final document draft included elements of the Egyptian proposal (like that the Secretary General should convene the conference by March 1, 2016 and a special representative was to be appointed). However, the US, the UK and Canada did not support the draft. Thus, in the absence of a consensus – among others over the Middle East zone – the final document was not adopted.

The failure of the decision on the Middle East zone put an extra pressure on the 2020 Review Conference,2 where Egypt and the United States agreed on language regarding the Middle Eastern zone free of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and reaffirmed the importance of establishing such a zone. The text also acknowledged the developments in the first two sessions of the new conference process on the Middle East zone established by the UN in 2018. The Swiss government, therefore, proposed to put up an open-ended working group to facilitate the dialogue.3 At the moment the parties seem to be at a loss regarding how to proceed with the Middle East zone. Arab frustration has increased and there is a sense of waiting. The Israeli position is a sense of satisfaction of having put the issue off at least till the next review conference. Iran feels relatively safe after the nuclear deal and with ally Syria having joined the Chemical Weapons Convention it could support the expansion of the NWFZ concept to that of a WMDFZ, which so far it has not.

- 1974

Iranian proposal for a nuclear weapon-free zone in the Middle East

- 1980

UN General Assembly supports ME NWFZ

- 1990

Egyptian President Mubarak proposes WMDFZ in the Middle East

- 1991

UN Security Council Resolution 687 supports Middle East WMDFZ

- 1991-1995

Arms Control and Regional Security (ACRS) group meetings

- 1995

NPT Review and Extension Conference adopts Middle East WMDFZ resolution

- 2010

NPT Review Conference agrees on steps for Middle East WMDFZ

- 2012

Planned Middle East WMDFZ conference postponed indefinitely

- 2015

NPT Review Conference draft on WMDFZ rejected by US, UK, and Canada

- 2019

Regional conference on WMDFZ (except Israel) issues political declaration

- 2022

10th NPT Review Conference affirms progress on Middle East WMDFZ

The Middle East and WMD Programmes: Current Status and Relevant Treaties

It has become obvious that different actors in the Middle East do have very different positions when it comes to the idea of creating a NWFZ in the Middle East. It is, therefore, important to understand the position of the key players, especially Egypt and the Arab League, Iran and Israel. Although not from the region itself, the EU has been very much committed to non-proliferation in the region in recent years, especially, but not only, as part of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action see LU-14, as you will see below.

Egypt/Arab League

As the first initiator/supporter of the idea of the Middle East NWFZ, then the WMDFZ, and the non-official leader and spokesman of the Arab states (Egypt has traditionally given the Secretary General of the Arab League except for a brief period), Egypt is frustrated at the failure of the initiatives to achieve a Middle East WMDFZ.

The frustration is shared by the other Arab states since their position has been defined to this day by their stance towards Israel, but their capabilities have been shifting away from WMD arsenals and programs: no Arab state has any nuclear weapon program or known biological program either, and Egypt is the last Arab state to be suspected with having remnants of its old CW program.

The Iranian nuclear program has been an added challenge, on the one hand exposing the lack of Arab ‘matching’ capabilities, on the other hand giving an extra urgency to the issue of the zone.

This urgency was reflected in the Egyptian proposal at the 2015 NPT Review Conference, and its failure increased the Arab frustration again.

Iran

Iran was the first to initiate the idea of the Middle East NWFZ and has supported the plan to this day. Iran was the victim of Iraqi chemical weapon attacks during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, consequently enthusiastically supported the CWC.

Although at first Iranian behavior seemed hesitant regarding the regional conference called by the 2010 NPT Review Conference, in the close run-up to it (late 2012) Iran announced its participation. While some say Iran announced its readiness only when it was clear that the conference would be postponed, its position as the president of the NAM (Non-Aligned Movement) at the time was an important pressure as well. Although Iran was not enthusiastic about the WMDFZ concept, late 2015 – with its Syrian ally safely within the CWC and the Iranian nuclear deal concluded – supporting the WMDFZ was politically possible.

Israel

The Israeli position to WMD arms control and disarmament has been defined by the “peace first, disarmament afterwards” sequencing (as reflected, among others, in the negotiations in the ACRS group).4

The initiative of the conference on the Middle East NWFZ in 2012 was accepted by the international community in the absence of Israel as it is not a party to the NPT, therefore, was not present in the 2010 Review Conference where the decision was taken.

EU position

The EU supports the 1995 resolution on the Middle East and regrets that the conference on the Middle East NWFZ/WMDFZ has not been held yet. It was responsible for the organization of two major international workshops on the zone in Brussels in 2011 and 2012 and a capacity building workshop in 2013 and is ready to promote the issue through similar events in the future.

Article 1 of the COUNCIL DECISION 2012/422/CFSP (23 July, 2012) ruled that „the Union shall support activities in order to further the following objectives: (a) to support the work of the Facilitator for the 2012 Conference on the establishment of a Middle East zone free of nuclear weapons and all other weapons of mass destruction; (b) to enhance the visibility of the Union as a global actor and in the region in the field of non-proliferation; … (d) to identify concrete confidence-building measures that could serve as practical steps towards the prospect of a Middle East zone free of WMD and their means of delivery; …”

In the EU statement on Nuclear Weapons Free Zones in January 2023 in Geneva, the EU reaffirmed “its full support for the establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction and their delivery systems, as agreed by NPT States Parties”.

While not an official European endeavor, there has also been activity from the scientific community, to bring key actors together in an academic setting to debate their differences in so-called “track 2” or “track 1.5 diplomacy”. For example, between 2010-2014 the self-called “Academic Peace Orchestra Middle East”, an initiative run by the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt in Germany, held a series of conferences/workshops and published some 40 Policy Briefs to contribute to the work of the Facilitator, Finnish Ambassador Jaakko Laajava.

Footnotes

-

In preparation for the conference and to support the Facilitator, Finnish diplomat Jaakko Lajaava, the Academic Peace Orchestra Middle East project (2011-2014) - under the leadership of Dr. Bernd Kubbig, HSFK/PRIF, Frankfurt - prepared some 40 Policy Briefs on the different aspects of an eventual WMDFZ in the Middle East. https://academicpeaceorchestra.com/ ↩

-

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 10th NPT Review Conference was held in August 2022. ↩

-

Middle East WMD-free zone - UNIDIR ↩

-

The Arms Control and Regional Security (ACRS) group was one of the five multilateral working groups within the Arab-Israeli peace process (1991-1995). ↩