While disarmament and non-proliferation obligations can thus be derived from different kinds of international norms, there are a number of institutions and tools that are particularly relevant in the context of compliance with and enforcement of these obligations. This section will cover international treaties, national implementation measures, international organisations, ad hoc instruments and sanctions. It will also discuss the role of national and international courts in ensuring compliance with and enforcing arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament obligations.

Treaties

Most arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament agreements take the form of international treaties (also see LU17). They often form the cornerstone of international regimes which may comprise additional elements. According to the classic definition, international regimes are structures for cooperation comprising ‘sets of principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations’.1 The treaties are usually concluded between states and contain legally binding rights and obligations. While they are tailored to specific weapons categories and may differ in scope and level of detail, most of the multilateral treaties in this field have some commonalities. The majority contain the obligation to implement the treaty provisions nationally, some envisage the establishment of international treaty organisations and some provide for measures to verify whether all member states comply with the treaty provisions. Several also contain provisions on how to deal with compliance concerns and violations, including in some cases a role for the UNSC.

National implementation measures

States are the primary addressees bound by multilateral arms control treaties. However, they also need to ensure that individuals and legal entities under their jurisdiction do not act against the obligations contained in international agreements. Many multilateral arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament treaties therefore explicitly oblige states parties to adopt or adjust national legislation to ensure compliance with the treaty obligations.

The treaties that prohibit nuclear weapons, nuclear weapons tests, biological and chemical weapons, for instance, have similar provisions for the national implementation of these bans. They all require that states parties take the necessary measures to ensure that the activities prohibited by the respective treaty are translated into national legislation which can be applied to anyone and anywhere on the state’s territory or under its jurisdiction. In some cases, the treaties themselves provide more detailed prescriptions on what these implementation measures should cover; in others, such as the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), the treaty remains vague, but states parties have identified examples for specific implementation measures through decisions at review conferences. However, the status and breadth of national implementation measures is far from coherent and varies between the different treaty regimes, and between the states parties within those regimes.

While the main actors in the implementation of arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament treaties are states, other actors can play a supporting role. International treaty organisations often take on that function (see below). Moreover, research institutions and non-governmental organisations can also provide support to states, as for instance the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), an autonomous institution within the UN system, and VERTIC, a non-governmental organisation based in London, are doing. The EU has adopted Joint Actions and Council Decisions in support of non-proliferation and disarmament treaties and has provided practical assistance for their national implementation.

The United Nations and international treaty organisations

International organisations have always played an important role in the field of non-proliferation and disarmament, including in compliance and enforcement. The UN fulfils some unique functions in this area, and some treaties established their own specific international organisations. These organisations serve different functions, which usually include support in the implementation of the treaties as well as a role in monitoring compliance and dealing with compliance concerns or cases of non-compliance.

The United Nations

The UN consists of four main organs: the General Assembly, the Security Council, the International Court of Justice and the Secretariat, which includes the Office for Disarmament Affairs. The General Assembly (UNGA) operates in plenary sessions and through six committees, with the First Committee focusing on disarmament and international security. UNGA resolutions are not legally binding but provide recommendations for UN member states. The UNSC, in contrast, can issue binding resolutions and implement coercive measures such as sanctions or even military action in carrying out its mandate to maintain international peace and security. With regard to compliance with and enforcement of arms control treaties, the UNSC can, under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, adopt enforcement measures to proliferation cases, as seen with sanctions against North Korea or Iraq’s disarmament in the 1990s. In addition, several treaties such as the BWC and Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) provide for UNSC involvement in addressing compliance concerns. Thus, in principle, the UNSC assumes an important role for compliance and enforcement. In reality, however, its effectiveness has often been hampered by (geo)political conflicts and the veto power of its five permanent members. The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) supports disarmament initiatives by promoting dialogue, transparency and confidence-building, and by supporting regional disarmament efforts, among other things. It also functions as the custodian of the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Chemical and Biological Weapons Use (UNSGM) which can be activated by any UN member state if there is credible evidence that a biological or chemical weapons attack may have occurred (Jakob/Kloth/Mergler 2024).2 Although the UNSGM is not a compliance or enforcement mechanism, its findings can inform political decisions related to compliance and enforcement in the field of chemical and biological weapons.

Treaty organisations

In addition to the UN, some non-proliferation and disarmament treaties have established specialised organisations to support their implementation. For example, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) fulfil this purpose in the chemical and nuclear fields. Treaty organisations provide forums for cooperation and consultation, facilitate communication between their members, and provide assistance and support in many areas related to treaty implementation. The latter often includes advice to ensure appropriate national implementation. Treaty organisations usually also play a role in maintaining compliance with the treaties, as they provide instruments to monitor and verify compliance, technical advice and forums in which compliance procedures can be carried out as foreseen in the treaties. While determining non-compliance and taking decisions about enforcement measures are ultimately political processes carried out by states, either individually or collectively, and not by the technical divisions of the organisation, these processes can be founded on the organisation’s scientific and technical findings.

The BWC and the Implementation Support Unit

The BWC has not established an international organisation like the OPCW or CTBTO. However, at the Sixth BWC Review Conference in 2006, an Implementation Support Unit (ISU) was created to provide administrative support to states parties and to the meetings agreed by the Review Conferences. In this function, the ISU provides assistance regarding the implementation of the BWC, its universalisation and facilitates the exchange of the Confidence-Building Measures. The ISU was set up within UNODA and currently has five core staff members. Its mandate needs to be renewed regularly, and this was last done at the Ninth Review Conference in 2022 for the period from 2023 to 2027.

The CWC and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons

The CWC established the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) as its treaty organisation. All CWC states parties are also members of the OPCW. The OPCW consists of three bodies: The Conference of the States Parties (CSP) and the Executive Council (EC), which are the two policy-making organs, and the Technical Secretariat (TS). With regard to compliance, the TS is responsible for carrying out the verification measures and investigations as foreseen by the CWC. The 41 members of the EC consider questions relating to the implementation of the CWC and to compliance/non-compliance and may bring matters to the attention of the CSP, or in cases of particular gravity and urgency, directly to the attention of the UNGA and the UNSC. The CSP is the primary body responsible for reviewing compliance with the CWC. In the event of suspected or proven non-compliance, it may decide on measures aimed at redressing the situation and restoring compliance, and it may also bring the issue to the attention of the UNGA and the UNSC.

The NPT and the International Atomic Energy Agency

Neither the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) nor the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) established their own treaty bodies. However, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), an independent international organisation established in 1956, assumes some of the functions for the NPT that would normally be fulfilled by such a treaty body. The IAEA comprises two policy-making bodies, the General Conference and the Board of Governors representing 35 states, as well as several offices and departments, including the Department of Safeguards which carries out the verification activities.

The TPNW does not refer explicitly to the IAEA. Under the NPT, however, all states parties that are classified as non-nuclear weapons states by the treaty are obligated to conclude safeguards agreements with the IAEA to enhance compliance with the treaty. Under these safeguards agreements, the IAEA conducts verification measures to ensure that nuclear materials and facilities are used for peaceful purposes only. Inspectors from the IAEA are tasked, among other things, with verifying and assessing member states’ compliance with the IAEA Statute and other pertinent agreements between states and the Agency, and to report any non-compliance to the IAEA’s Director-General. The Director-General informs the Board of Governors, which then reports the case to the member states, the UNGA and the UNSC. The Board may also take different enforcement measures, such as suspension of assistance or of membership rights, to restore compliance. Moreover, member states may involve the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to settle disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the IAEA Statute or to seek advisory opinions on legal questions regarding IAEA activities (see below).

The CTBT and the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty Organization

Had the CTBT entered into force, it would have established the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty Organization. Even though the specific requirements for the entry into force have not yet been met, the signatories to the CTBT decided in 1996 to establish an interim organisation: The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) which carries out the functions that would support monitoring compliance with the CTBT, such as operating an extensive network of seismic and other monitoring stations able to detect nuclear (test) explosions. In the event of a violation being detected, any follow-up action would fall to the UNSC or the international community as long as the CTBT has not entered into force.

Ad hoc institutions established to address compliance problems

In some instances, ad hoc institutions were established in response to specific compliance-related events. Examples include the commissions set up by the UNSC in relation to Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programmes, as well as the mechanisms established by the UN and the OPCW in response to Syria’s use of chemical weapons and violations of the CWC, and the Joint Comprehensive Programme of Action (JCPOA) created to deal with concerns about Iran’s compliance with its NPT obligations.

Disarmament of Iraq’s nuclear, chemical and biological weapons

Iraq had maintained offensive nuclear, chemical and biological weapons programmes since the 1970s, which were all detected and dismantled in the wake of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the subsequent Second Gulf War. Iraq had ratified the NPT in 1969, so its nuclear activities violated the provisions of the treaty. It was a signatory to the BWC, which would have required it to act in the spirit of that treaty, but only became a full member in 1991. The CWC was not concluded until 1992, and Iraq acceded to it in 2009. It has since declared and destroyed the remnants of its chemical weapons programme under OPCW verification. As part of the ceasefire agreement after the war in 1991, the UNSC decided that these weapons programmes would be terminated and dismantled under international supervision. For the nuclear weapons programme, the IAEA took on that task. Since there were no organisations covering chemical or biological weapons at the time, the UNSC set up the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM) composed of national experts and equipped with a mandate to monitor the destruction of all of Iraq’s biological and chemical weapons stockpiles and related facilities. In 1999, the UNSC set up the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC). This latter organisation replaced UNSCOM and continued its mandate to destroy and dismantle all of Iraq’s chemical and biological weapons, as well as storage and production facilities by 2007. Unlike UNSCOM, UNMOVIC inspectors performed their duties as UN personnel and not in their national capacities. In the course of their work, both commissions succeeded in uncovering hitherto unknown information that contributed to eliminating Iraq’s nuclear, biological and chemical weapons programmes.

Chemical weapons disarmament in Syria

Between 2012 and 2018, numerous chemical weapons attacks were carried out in Syria. When the first reports of chemical attacks came out of Syria in 2012 and 2013, Syria was not yet a member of the CWC, and the OPCW thus had no authority to address these allegations. Instead, the UNSGM was activated and confirmed four chemical weapons attacks, including the particularly severe attack on Ghouta in August 2013, without, however, attributing responsibility. In the wake of this latter attack and under political pressure from Russia and the USA, Syria acceded to the CWC and was thus subject to its disarmament and verification obligations. To carry out the highly demanding task of dismantling the Syrian chemical weapons programme as quickly as possible in the midst of civil war, the OPCW and the UN established a Joint Mission in 2013. Under its supervision, all chemical weapons stockpiles and production facilities declared by Syria to the OPCW were destroyed or converted to peaceful purposes by 2016. However, from 2014 onwards concerns arose that Syria might not be fully complying with its obligations under the CWC. In response, several other ad hoc instruments were established within the OPCW Technical Secretariat and by the UNSC. The Declaration Assessment Team (DAT has been addressing gaps and inconsistencies identified by OPCW inspectors in Syria’s chemical weapons-related declarations since 2014, and until the end of 2024, it reported that the declarations were still incomplete and inaccurate. The Fact-Finding Mission (FFM), also established in 2014, follows up on allegations of chemical weapons attacks to determine whether chemical weapons were indeed used. It has so far investigated 74 alleged attacks and confirmed 20. Between 2015 and 2017, the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) was mandated by the UNSC to identify the perpetrators of chemical weapons attacks in Syria, which it did in six of the eleven cases it investigated (four attacks were attributed to the Syrian government at the time and two to the so-called Islamic State). After the JIM’s mandate expired in 2017 due to a Russian veto in the UNSC, the Investigation and Identification Team (IIT) was set up in 2018 as part of the OPCW TS following a majority decision of OPCW member states. Similar to the JIM, the IIT is tasked with identifying those responsible for confirmed chemical weapons attacks in Syria. As of February 2025, it had named the Syrian government as the perpetrator in five cases and the so-called Islamic State in one.3 In response to these proven violations of the CWC, states parties have, by majority decision, invoked the compliance procedures of the treaty, suspending several of Syria’s membership rights, recommending restrictions on the trade of listed chemicals with Syria, and bringing the matter to the attention of the UNSC and UNGA. It is as yet unclear whether and how Syria’s CW policy will change after the fall of Assad and his government in 2024.

The Syrian case

- 2012–2013

First chemical attacks are reported in Syria. The UN confirms four, including the major Ghouta attack in August 2013, but doesn’t attribute responsibility.

- 2013

Under pressure from the US and Russia, Syria joins the CWC and declares its chemical weapons programme to the OPCW. The OPCW-UN Joint Mission is created to dismantle Syria’s chemical weapons program.

- 2014

Doubts emerge over Syria’s compliance with the CWC. The OPCW sets up the Declaration Assessment Team (DAT) to review inconsistencies in the declaration, and the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) to investigate alleged attacks. The FFM has confirmed 20 out of 74 allegations investigated as of March 2025.

- 2015–2017

The OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM), established by the UN Security Council, identifies perpetrators for chemical weapons attacks, attributing four attacks to the Syrian government and two to ISIL. Russia blocks renewal of the JIM’s mandate in 2017.

- 2016

The elimination of Syria’s declared chemical weapons stockpiles and production sites is completed under OPCW verification.

- 2018

Following a decision by CWC states parties, the OPCW creates the Investigation and Identification Team (IIT) to identify those responsible for confirmed chemical weapons attacks. As of March 2025, the IIT has identified the Syrian government as perpetrator in five attacks and ISIL in one.

- 2020 and 2023

OPCW members suspend some of Syria’s membership rights and take additional measures in response to its non-compliance with the CWC.

- 2024

The DAT once more reports that Syria’s declarations remain incomplete. Assad’s fall raises questions about the safety, security and future of Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles and facilities.

- 2025

The interim government of Syria publicly announces its intention to eliminate the remains of the chemical weapons programme, cooperate with the OPCW and restore Syria’s compliance with the CWC.

Iran’s nuclear programme and the Joint Comprehensive Programme of Action (JCPOA)

The JCPOA is an agreement that was concluded in 2015 between China, France, Germany, Iran, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The agreement was a response to years of Iranian nuclear activities and concerns raised about whether these activities were entirely peaceful, as Iran claimed, or whether they were part of an illegal nuclear weapons programme in violation of Iran’s obligations under the NPT.

Due to these compliance concerns, the United States and the EU had imposed sanctions on Iran. These were to be incrementally lifted under the JCPOA in return for Iran rolling back specific parts of its nuclear programme under IAEA verification in compliance with its JCPOA obligations. The agreement was also approved by the UNSC in Resolution 2231 (2015). However, implementation proved difficult. The Western parties to the agreement suspected Iran of violating its obligations, and in 2018, the United States withdrew from the JCPOA. All Western parties to the JCPOA kept sanctions in place in reaction to their concerns about Iran’s non-compliance with the JCPOA, which were supported by the results of the IAEA’s verification activities. In 2019, Iran openly resumed nuclear activities that are proscribed under the JCPOA, and since 2021 has ceased all collaboration with the IAEA meaning that the Agency can no longer carry out its verification activities as foreseen in the JCPOA. The IAEA Board of Governors has repeatedly issued resolutions by majority vote censuring Iran for not fulfilling its JCPOA obligations and not cooperating with the IAEA. In its coordinating role, the EU has attempted to facilitate negotiations that would allow the revival of the agreement, but as of 2024, this has been to no avail – the JCPOA still lies dormant.

Enforcement tools

Given the nature of the international system with its lack of an overarching authority, enforcement of non-proliferation and disarmament norms is complicated. Generally speaking, the use of (military) force against another state is prohibited according to Article 2, para 4 of the UN Charter and customary law. But the UNSC has the authority to authorise the use of force against another state if it determines the existence of a threat to or breach of the peace, or act of aggression within the meaning of Article 39 of the UN Charter. In the past, the UNSC declared the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction a threat to international peace and security. However, the adoption of a UNSC resolution authorising the use of force in case of biological, chemical or nuclear weapons use is highly unlikely given the current geopolitical climate and the veto power of its five permanent members (P5). Another exception to the use of force is self-defence. In the context of self-defence, military force was applied in 2003, for example, when the US and the United Kingdom (UK) launched a military intervention in Iraq over their allegations that the latter continued to possess weapons of mass destruction and that an armed attack with these weapons, above all on the US, would be very likely. Self-defence requires either that an armed attack has already taken place or is imminent. Neither of these requirements were fulfilled in the case of Iraq, which is why the US and UK military intervention in Iraq and the ousting of Sadam Hussein was considered illegal.4 The US and France – neither with the authorisation of the UNSC or on the basis of self-defence – carried out limited airstrikes against Syria in response to a chemical weapons attack in 2017, with the stated goal of reducing the risk of further similar attacks. Whether these attacks were legally justified remains highly contested. Some argued that the attacks were part of a humanitarian intervention (a third exception to the use of force). But the concept and legality of a humanitarian intervention as an official exception to the use of force remains highly contested.5

Another, more frequently applied instrument available to states in this context is sanctions. Sanctions are enforcement tools aimed at eliciting or restoring compliant behaviour from actors in line with specific norms or agreements, often by raising the cost of unwanted actions.6 The term ‘sanctions’ generally refers to economic sanctions, but it might also include travel bans on individuals, visa restrictions, limited diplomatic engagement or restricted participation in cultural events. Sanctions can be applied unilaterally by individual states, by groups of states, or collectively with a UNSC mandate under UN Charter Chapter VII. In the latter case, all UN members are obliged to implement these sanctions.

The most common way of classifying sanctions is based on their scope, distinguishing between comprehensive sanctions and targeted or ‘smart’ sanctions. Comprehensive sanctions are characterised by wide-ranging restrictions on trade, finance and other interactions, designed to isolate the state and put maximum pressure on its government. Comprehensive UN sanctions were, for example, enacted against Iraq following its invasion of Kuwait in 1990. These sanctions led to a humanitarian catastrophe in Iraq, which prompted a re-evaluation of their scope. The concept of ‘smart’ or targeted sanctions was developed to focus on individuals, entities or sectors with the aim of minimising the impact on the general population and allowing for more flexibility in a changing context. Examples of targeted sanctions include travel bans, individual or entity asset freezes, sanctioning industries or sectors crucial for a state’s economy or limiting diplomatic relations. Since 2000, targeted sanctions have been implemented not only by the UN but also by several individual states and regional organisations, which developed national sanctions programmes. These have included the African Union, Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the US.

The impact of any sanctions should be constantly monitored to ensure they are having the desired effect and to account for changing circumstances. For example, sanctions might need to be broadened to address a web of proxies and alternative supply chains used to evade an import ban. Sanctions are a complex trade-off between the restrictions needed to compel a change in behaviour and political and ethical acceptability.

Sanctions mandated by the UNSC related to non-compliance with non-proliferation and disarmament norms are currently in place against North Korea (over its nuclear weapons programme and tests). Examples of sanctions related to arms control and disarmament imposed by individual states and the EU include those against Syria (over its chemical weapons possession and use), Iran (over its suspected nuclear programme) and Russia (over its suspected use of chemical weapons agents in assassinations and on the battlefield in Ukraine).

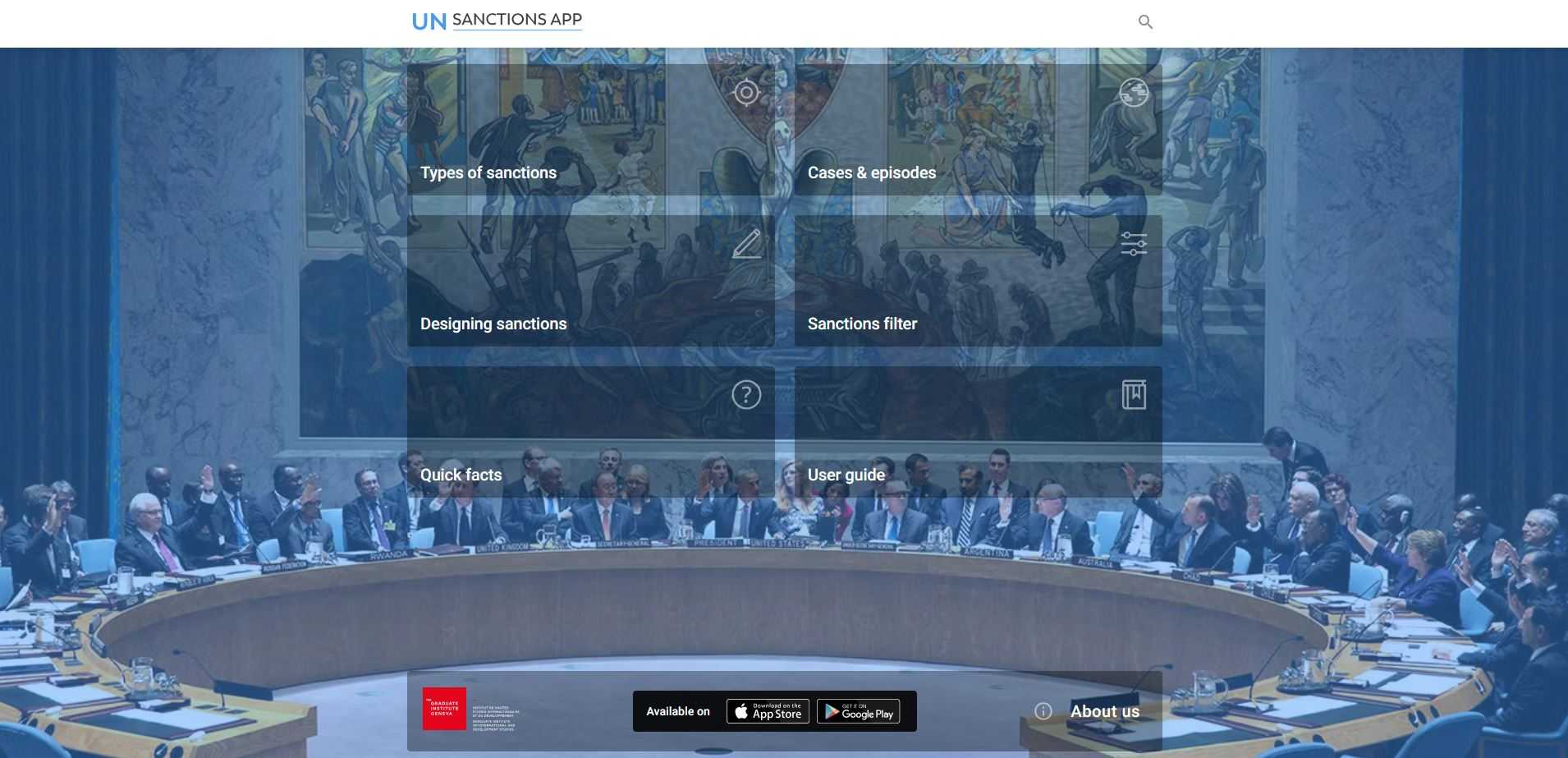

Introducing the UN Sanctions App

Footnotes

-

Krasner, Stephen D. (ed.) 1983. International Regimes. Cornell University Press, 2. ↩

-

Jakob, Una/Kloth, Stefan/Mergler, Ines. 2024. “Investigating Alleged Biological Weapons Use – Strengthening the UN Secretary General’s Mechanism”, PRIF Report 7/2024, DOI: 10.48809/prifrep0724 ↩

-

All reports by the IIT are available at https://www.opcw.org/iit. ↩

-

Heintschel von Heinegg, Wolff. 2025. “Iraq, Invasion of 2003”, in: Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Oxford University Press, available at: https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1820.https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1820 ↩

-

Scharf, Michael P. 2019. “Responding to Chemical Weapons Use in Syria”, in: Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 51 (1): 189–199. ↩

-

van Bergeijk, Peter/Biersteker, T. 2015. “How and When Do Sanctions Work? The Evidence” in: On Target? EU Sanctions as Security Policy Tools, January, https://doi.org/10.2815/710375 ↩