Nuclear weapons production

When a country decides to develop a nuclear weapons programme it needs to choose whether to enrich uranium, or to produce and separate plutonium. All the nuclear weapon states have produced weapons-grade uranium in the past, but the states under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) have ended HEU production for weapons (see LU05). Nowadays, HEU for military purposes is still produced by India, Pakistan and probably North Korea. The plutonium pathway is less costly than the uranium one. Moreover, plutonium has a lower critical mass than HEU. The United States, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, India, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea have reprocessing programmes for plutonium separation. Although all states under the NPT stopped separating plutonium for its use in weapons, the production of plutonium for military purposes is believed to be continued in India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel.

Fissile material and weapons stockpiles

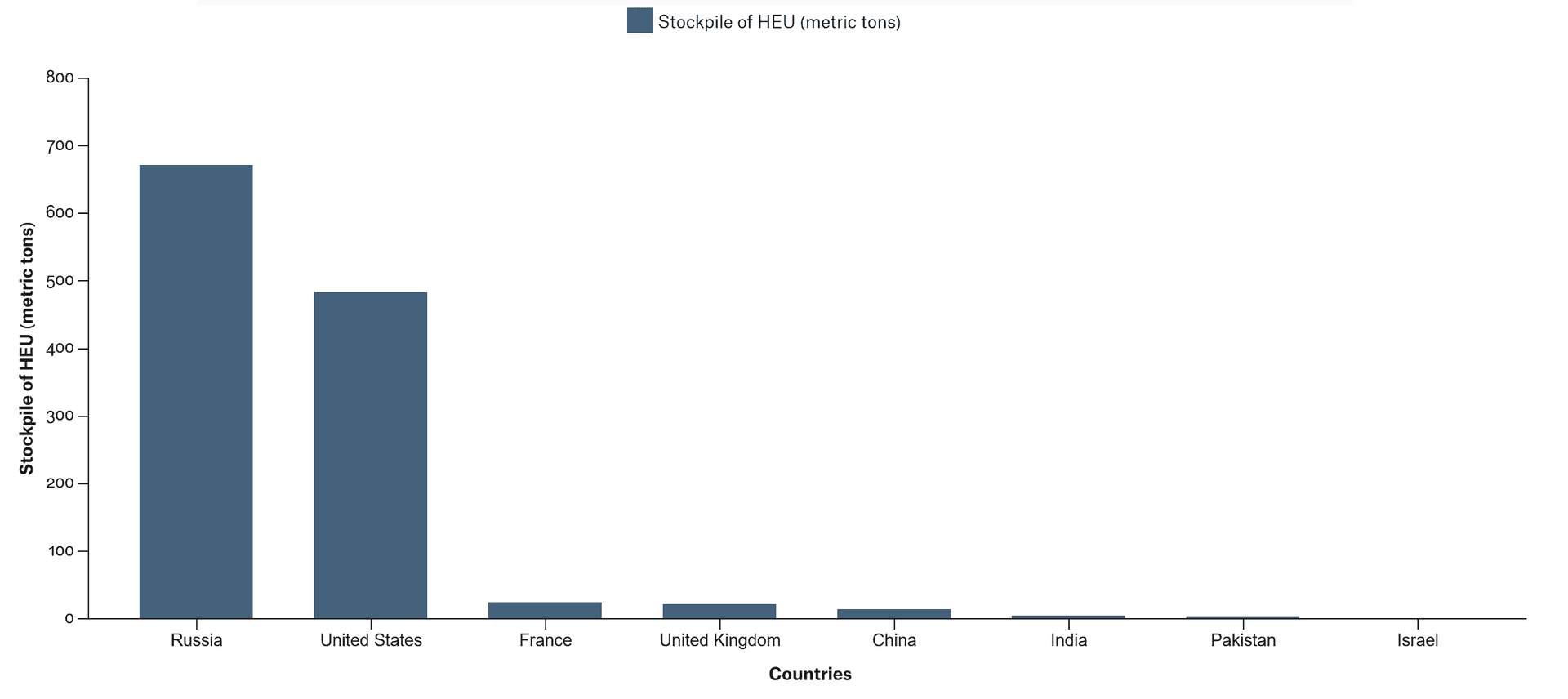

Fissile material stockpiles are divided into stockpiles of HEU and plutonium available for weapons. Since HEU is used in civil nuclear reactors, both military and civilian stocks of HEU are addressed. According to the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM)1, for HEU, the 2022 global inventory was 1,335 ± 125 metric tons, of which 99% is held by nuclear weapon states, mainly Russia and the USA.2 Only the United States and the UK publish official statements regarding their military stockpiles, meaning that for other countries, figures are uncertain. This is particularly true for the Russian stockpiles. The current estimates of military stockpiles of HEU, based on the information provided by the International Panel in Fissile Material can be seen below.

Table HEU. Stockpiles of HEU (IPFM, 2022)34

| Country | Stockpile of HEU (metric tons) |

|---|---|

| Russia | 672 ± 120 |

| United States | 483.4 |

| France | 24.6 |

| United Kingdom | 21.9 |

| China | 14.0 |

| India | 4.5 |

| Pakistan | 4.0 |

| Israel | 0.3 |

Note that the IPFM does not assign an HEU stockpile to North Korea. Other estimates suggest that North Korea could possess 0.5–2.1 metric tons of HEU.5 The production of HEU has largely ended. Both the United States and Russia, along with other countries, stopped producing HEU between the 1970s and 1990s.

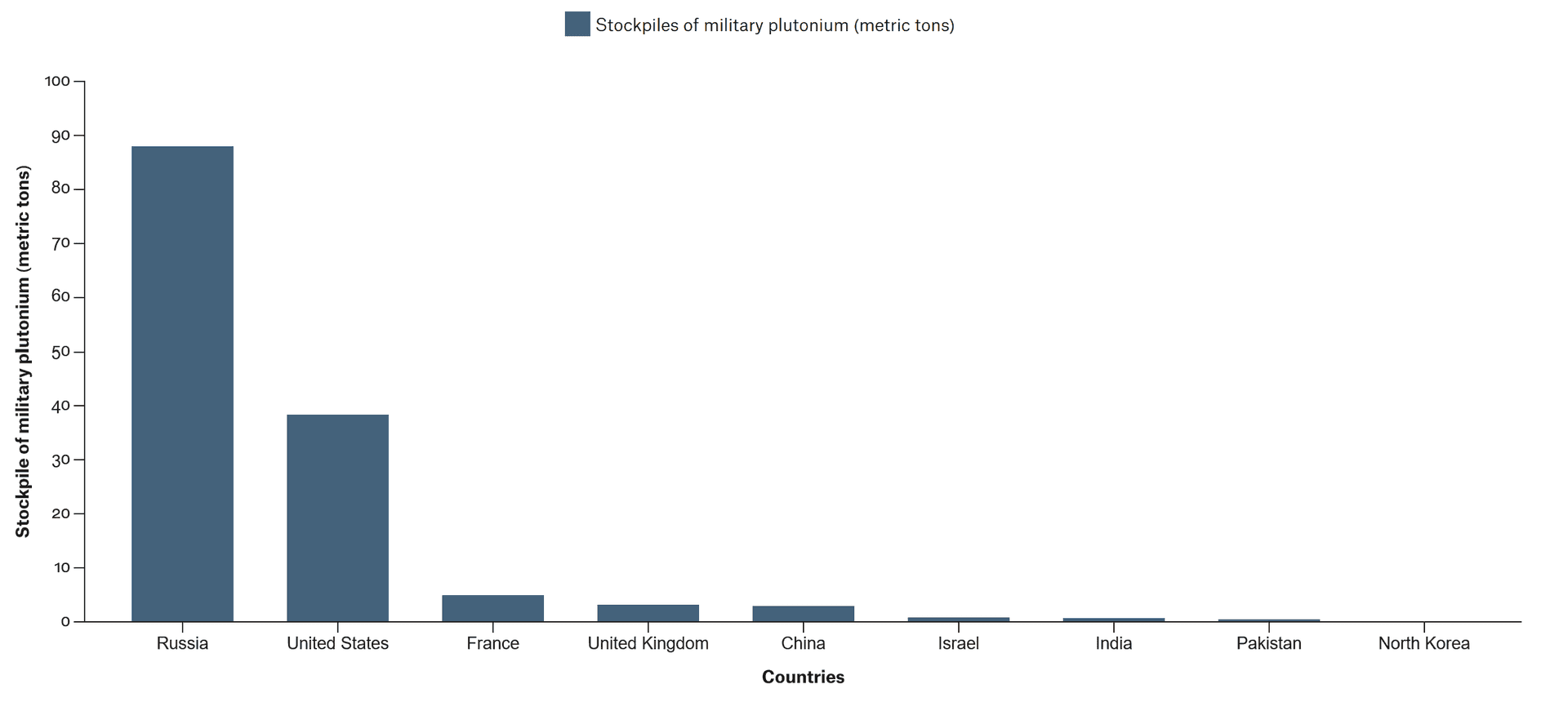

The global stockpile of military plutonium is estimated to be 140 ± 10 metric tons (IPFM, 2022) Here, too, the majority of the material is held by Russia and the United States (see Table Pu).

| Country | Stockpile of HEU (metric tons) |

|---|---|

| Russia | 88 |

| United States | 38.4 |

| France | 4.9 |

| United Kingdom | 3.2 |

| China | 2.9 |

| Israel | 0.83 |

| India | 0.71 |

| Pakistan | 0.46 |

| North Korea | 0.04 |

For plutonium production, the nuclear weapon states under the NPT all seized their production during the 1980s and 1990s, while India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea still produce, see

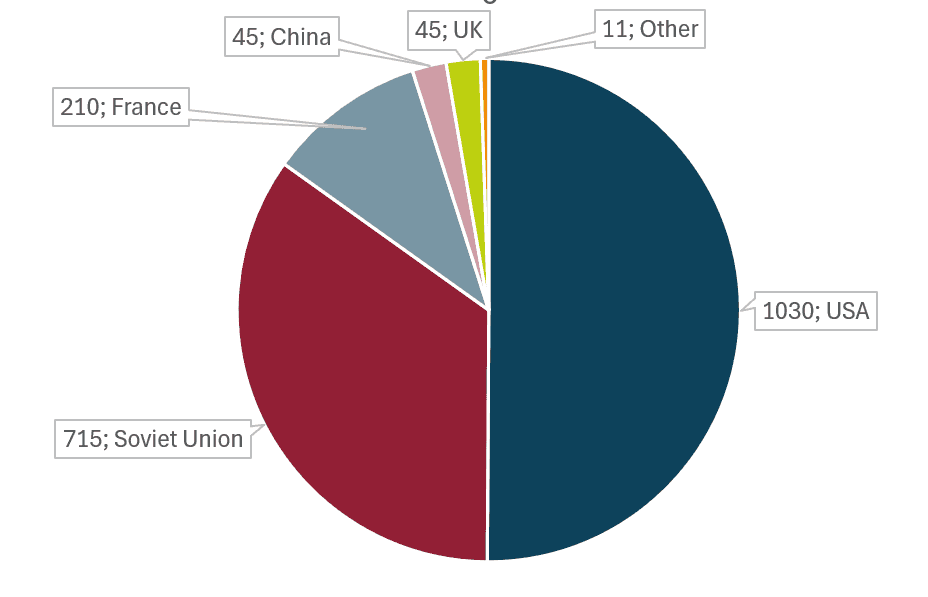

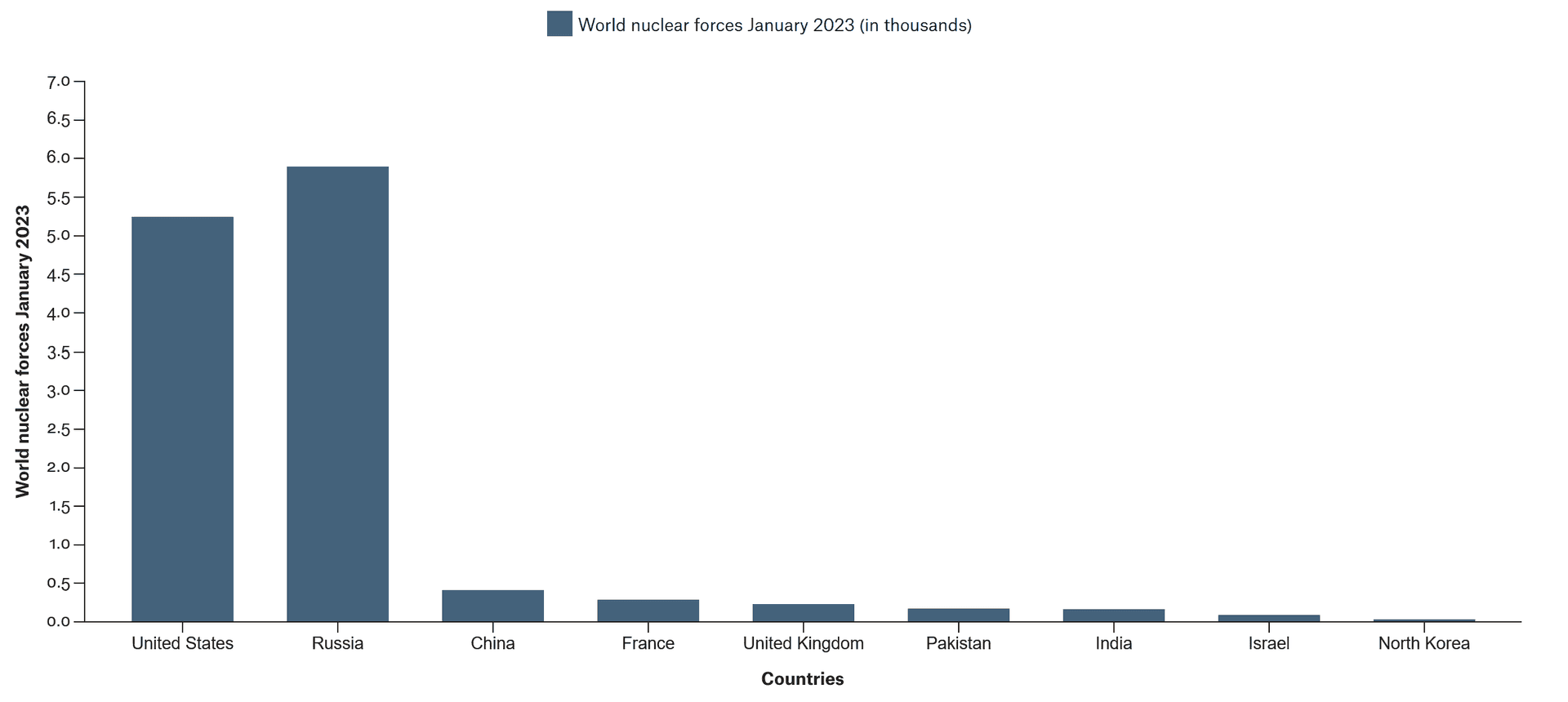

The word “weapons stockpile” has different meanings in different countries and different contexts. Here we adopt the definition used by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) in their yearly report on the World’s Nuclear Forces.8 This definition includes all nuclear warheads that are deployed or in storage, as well as warheads that are retired but not yet dismantled, i.e. warheads that can be deployed with short preparation time. The existing warhead stockpiles based on this definition are shown here:

The total number of warheads worldwide according to SIPRI is 12,512.

Nuclear weapons testing

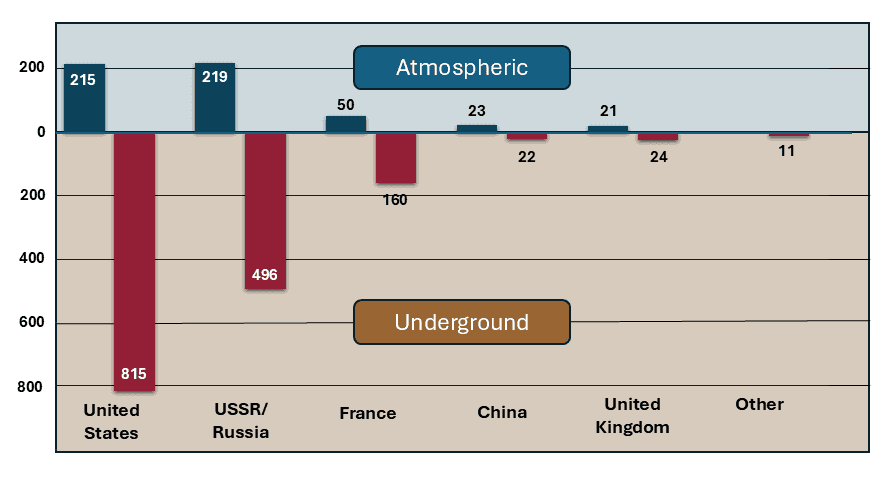

Test ban treaties

Several international treaties to limit or completely ban nuclear testing have been negotiated, starting with the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) in 1963. The full name of this treaty is the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, and it bans all nuclear test explosions except those underground. The PTBT was both signed and ratified by the United States, Soviet Union and United Kingdom, but not by France and China. The PTBT had a significant effect as nearly all nuclear tests moved underground once it had come into force. This treaty is still in effect.

Another important treaty is the Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), which was adopted between the United States and the Soviet Union in 1974. The full name of this treaty is Treaty on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear Weapon Tests and it limits the yield of a test device to 150 kilotons. This was a bilateral treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union and was signed and ratified by both. As with the PTBT, the TTBT is still in effect.

In 1996, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). This treaty bans all nuclear test explosions including peaceful testing. It has been signed and ratified by the majority of the Earth’s nations, but has not entered into force since not all the required states have ratified it. In its Annex II, there is an agreed list of 44 countries that must sign and ratify the treaty for it to enter into force. Of these “Annex II states”, eight signatures and/or ratifications are still missing: China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia and the United States. The United States and Russia have both signed but not ratified the treaty.

In preparation for the CTBT to enter into force, an extensive verification regime has been developed in order to monitor compliance with the Treaty. This is handled by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization. The verification regime includes three components:

- The IMS – the International Monitoring System which is a network of monitoring stations based on different detection technologies and with stations detecting seismic disturbances (seismic), soundwaves in the ocean (hydroacoustics), infrasound and radionuclides. For more details on the monitoring systems, see Chapter 5.

- The IDC – the International Data Centre in Vienna where the CTBTO headquarters is located. This centre receives and processes data from the IMS and distributes it to the CTBTO member states.

- OSI – on-site inspections will make it possible to collect data on the ground, once the CTBT enters into force.

It should be noted that the IMS and the CTBT successfully detected the nuclear weapons tests performed by North Korea in 2006, 2009, 2013 and 2016.

Nuclear disarmament

While the NPT prohibits the development of nuclear weapons by non-nuclear weapon states, the five recognised nuclear weapon states – the United States, Russia, France, China and the United Kingdom are exempt from this prohibition. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that Article VI of the NPT requires that the nuclear weapon states

pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.

Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), Article VI

Nuclear disarmament is the process of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons dismantlement

Dismantlement is one phase of the disarmament process. It refers to the physical separation of the weapons components, such as high explosives and nuclear material, so it can no longer produce a nuclear yield. The dismantlement of nuclear weapons reached its peak in the 1990s, when the US alone dismantled weapons at a rate of 1,000 per year.9 But with the shift of resources, the US started to invest in maintenance and life extension programmes for the existing warheads instead.10 The US has one operational weapon disassembly facility at Pantex, Texas. Russia has two such facilities at Lesnoy and Trekhgorny. Typically, disassembly facilities are also weapon assembly facilities, which makes sense in terms of the type of machinery and experience needed to handle a particular nuclear weapon. The steps involved in the dismantlement of a nuclear weapon depend on the type of weapon.

In general terms, the steps followed in dismantlement are11:

- Removal of the weapon from the delivery system

- Removal of the weapon from its outer shell and other components

- Separation of high explosives and fissile material core

- Destruction, storage or reuse of various weapon components

Verification

Verification will be an essential part of any disarmament treaty that comes into force. Verification can be defined as

iterative and deliberative processes of gathering, analysing, and assessing information to enable a determination of whether a State Party is in compliance with the provisions of an international treaty or agreement”.

International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification

Verification develops confidence among and between states, increasing transparency and encouraging states to engage in future agreements. The verification of the arms control treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States, “New START”, which came into force in 2011, was conducted indirectly. The warheads were counted indirectly, via the number of delivery vehicles that were associated with these weapons. A disarmament treaty that imposes limits on the number of weapons in an arsenal will require a different verification system, since it might require the verification of individual nuclear warheads in storage or entering the dismantlement queue (for more information, see Learning Unit 05 or Learning Unit 20).

Verification of the dismantlement of a nuclear weapon is an important element of securing a transparent and irreversible nuclear weapons reduction process. The verification of individual nuclear weapons is tricky, since the design of a nuclear weapon is highly classified information that cannot be revealed to international inspectors, even in the event of dismantlement. Therefore, the verification methods used should not reveal classified information so as to keep the host party information secret and to fulfil non-proliferation requirements. The verification methods applied in a disarmament verification treaty should enable a compromise between reliably verifying that the inspected warhead is authentic and not disclosing information about its design.

Individual institutional research groups, such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), have been performing research on the development of methods to assist the inspection of nuclear weapons dismantlement and destruction.12 The group of MIT scientists proposed a verification method using neutron beams and an isotopic information barrier filter to inspect certain properties of the warhead without revealing confidential information on the warhead design.

Initiatives such as the International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification (IPNDV) work on identifying challenges related to nuclear disarmament verification and developing procedures and technologies to address these challenges.

The IPNDV was started in December 2014 based on cooperation between the U.S. Department of State and the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI). Later, the IPNDV incorporated different countries, with and without nuclear weapons, reaching 25 states in 2024.

The main goals of the IPNDV are:

- to identify gaps and technical challenges associated with monitoring and verifying nuclear disarmament throughout the nuclear weapons life cycle;

- to build and diversify international capacity and expertise on nuclear monitoring and verification.

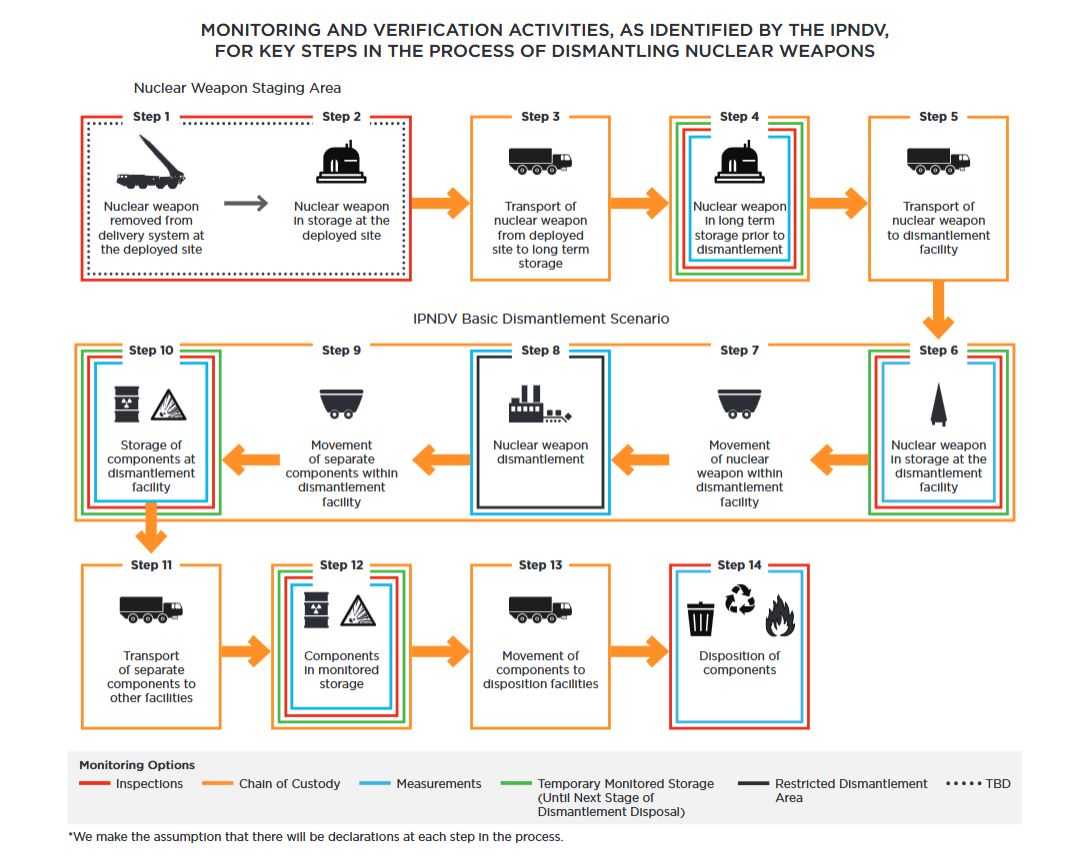

To better understand the verification of a nuclear dismantlement process, the IPNDV developed a 14-step model, from the removal of nuclear weapons from its delivery system to their disposition in separate components.

The IPNDV partners worked with this 14-step nuclear weapons dismantlement life cycle to propose different procedures and technologies for monitoring and inspecting the various processes. Measurement technologies applied in some of these steps include radiation detection equipment, calorimeters and explosive identification systems. Elements that could be part of the chain of custody procedure include container assessment technologies, tamper indicating devices and seals. Monitoring procedures suggested by the IPNDV for some of the steps are surveillance technologies and portal monitors.

Weapon material disposal

To make sure that weapons material is not used to make new nuclear weapons, different approaches to dispose of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium are discussed. The options under discussion are processing the material in current and future reactors, vitrification of the material with high-level nuclear waste for disposal in an engineered repository or even launching the material in packages into solar orbit from the Earth. Due to economic, environmental and non-proliferation reasons (protecting the material from terrorist groups or rogue nations that might attempt to acquire it for use in nuclear weapons), the use of nuclear weapons material demands strict measures, imposing limitations on its application for energy production.13 For example, to use weapons-grade plutonium in a reactor, the material would need to be used to fabricate mixed-oxide fuel (MOX). However, the costs related to this process would be much higher than those for fabricating LEU. And since there are just a few reactors that are designed to use MOX, there will be the costs of the secure shipping and storage of the material as well

Footnotes

-

The International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) is an independent group of arms control and non-proliferation experts from both nuclear weapon and non-nuclear weapon spates. ↩

-

IPFM. Global Fissile Material Report 2022. Fifty Years of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Nuclear Weapons, Fissile Materials, and Nuclear Energy. A report of the International Panel on Fissile Material, July 2022 ↩

-

IPFM. Global Fissile Material Report 2022. Fifty Years of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Nuclear Weapons, Fissile Materials, and Nuclear Energy. A report of the International Panel on Fissile Material, July 2022 ↩

-

Please note that Russia’s stockpiles are given as 672 +/- 120 ↩

-

Christopher, Grant/Wingo, Hailey. 2023. North Korean Operations of the Experimental Light Water Reactor. Vertic. Available at: https://www.vertic.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/TV172-REV2.pdf#page=7, Trust & Verify Issue 172 ↩

-

IPFM. Global Fissile Material Report 2022. Fifty Years of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Nuclear Weapons, Fissile Materials, and Nuclear Energy. A report of the International Panel on Fissile Material, July 2022 ↩

-

Please note that Russia’s stockpiles are given as 88 +/- 8. ↩

-

Kristensen, H. 2023. 2023. SIPRI Yearbook 2023, 7. World nuclear forces, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Sweden. Available at: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4313733/sipri-yearbook-2023-7/5123325/ ↩

-

https://open.defense.gov. The Trump Administration has not disclosed stockpile and dismantlement numbers for 2018. ↩

-

Kristensen, Hans M. “Obama Administration Announces Unilateral Nuclear Weapon Cuts”, in: Federation of American Scientists 11, January 2017. Available at: https://fas.org. ↩

-

Bunn M. 2008. – Reykjavik Revisited: Steps Toward a World Free of Nuclear Weapons, Chapter 5: Transparent and Irreversible Dismantlement of Nuclear Weapons. Available at: https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/9780817949211_ch5.pdf ↩

-

“How to dismantle nuclear bombs” in MIT News. 2019. Available at : https://news.mit.edu/2019/verify-dismantle-nuclear-bombs-0927 ↩

-

Berkhout, F./ Diakov, A./Feiveson, H./ Hunt, H./ Lyman, E./Miller, M./von Hippel, F.: “Disposition of Separated Plutonium”, in: Science and Global Security 3 (3–4), March 1993: pp. 161–214;

Von Hippel, F./Miller, M/Feiveson, H/Diakov, A./Berkhout, F.: “Eliminating Nuclear Warheads”, in the Scientific American, 269, pg. 4-49, Aug. 1993. ↩