Introduction

The institutional set-up of EU non-proliferation and disarmament policy

The 2003 EU Strategy against the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction

In December 2003, at the same time as the release of the European Security Strategy, the European Council adopted its first Strategy against the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), opening a new chapter for the EU’s role in the field.

The adoption of the EU WMD Strategy did not herald a radical departure from traditional EU non-proliferation policy; rather, it was grounded in the EU’s tradition of:

- rule of law;

- multilateralism;

- economic and political pressure on third states;

- focusing on the political causes of international problems;

- international cooperation.1

As the first programmatic EU document to comprehensively set out EU priorities and means of action in non-proliferation and disarmament, it covers the nature of the threat of WMD proliferation, EU tools to address the threat and a concrete action plan to implement the European response. The threat analysis encompasses a broad array of scenarios that may affect the EU, its member states or the broader international non-proliferation regime, including terrorist attacks using WMD. Potential measures include:

- a commitment to address the root causes of instability;

- different forms of coercion, such as the use of force under Chapter VII of the UN Charter; and

- close cooperation with key partners.2

Following the adoption of the WMD Strategy, the EU developed institutional and financial capabilities to implement it in practice.3 The position of the Personal Representative on non-proliferation of WMD reporting to the HR was created in 2003 and occupied by Italian diplomat Ms Annalisa Giannella. A new non-proliferation unit was set up in the Council Secretariat, separate from the small team of civil servants dealing with non-proliferation at the European Commission.

The 2008 New Lines for Action in combating the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their delivery systems

In 2008, Brussels sought to boost the overall coordination of non-proliferation policies in the EU and its member states by adopting the New Lines for Action in combating the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their delivery systems.

Among the changes introduced by the institutional reshuffling of the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon, the two non-proliferation units, that is the Council Secretariat dealing with political aspects and that in the Commission Services in charge of technical matters, were merged under the newly established EEAS. The reshuffling also created the position of permanent chair of the Working Group on Non-Proliferation, which brings together the heads of the non-proliferation units in the foreign ministries of EU member states. The post of Personal Representative was renamed Principal Adviser and Special Envoy for Non-proliferation and Disarmament in 2013, and Annalisa Giannella, who had been Personal Representative for non-proliferation of WMD since 2003, was replaced by Polish diplomat Jacek Bylica in 2012, later succeeded by Dutch diplomat Marjolijn van Deelen in 2020, and subsequently by senior Commission official Stephan Klement, who took up the post in 2024.

One of the most noteworthy innovations introduced by the WMD Strategy is the ‘non-proliferation clause’. It was drafted in 2003 for inclusion in agreements between the EU and third countries. The clause consists of a binding commitment to adhere to all the agreements that have been ratified in the field of non-proliferation, accompanied by encouragement to accede to all agreements that the partner country in question had not yet joined. In theory, this enables the EU to cancel an agreement if a partner country violates its non-proliferation obligations. However, the success of this policy has been mixed. While many countries, such as Indonesia or South Korea, signed agreements with the EU that include the non-proliferation clause, major players, including India, held back.4

Support for international regimes: Cooperation projects

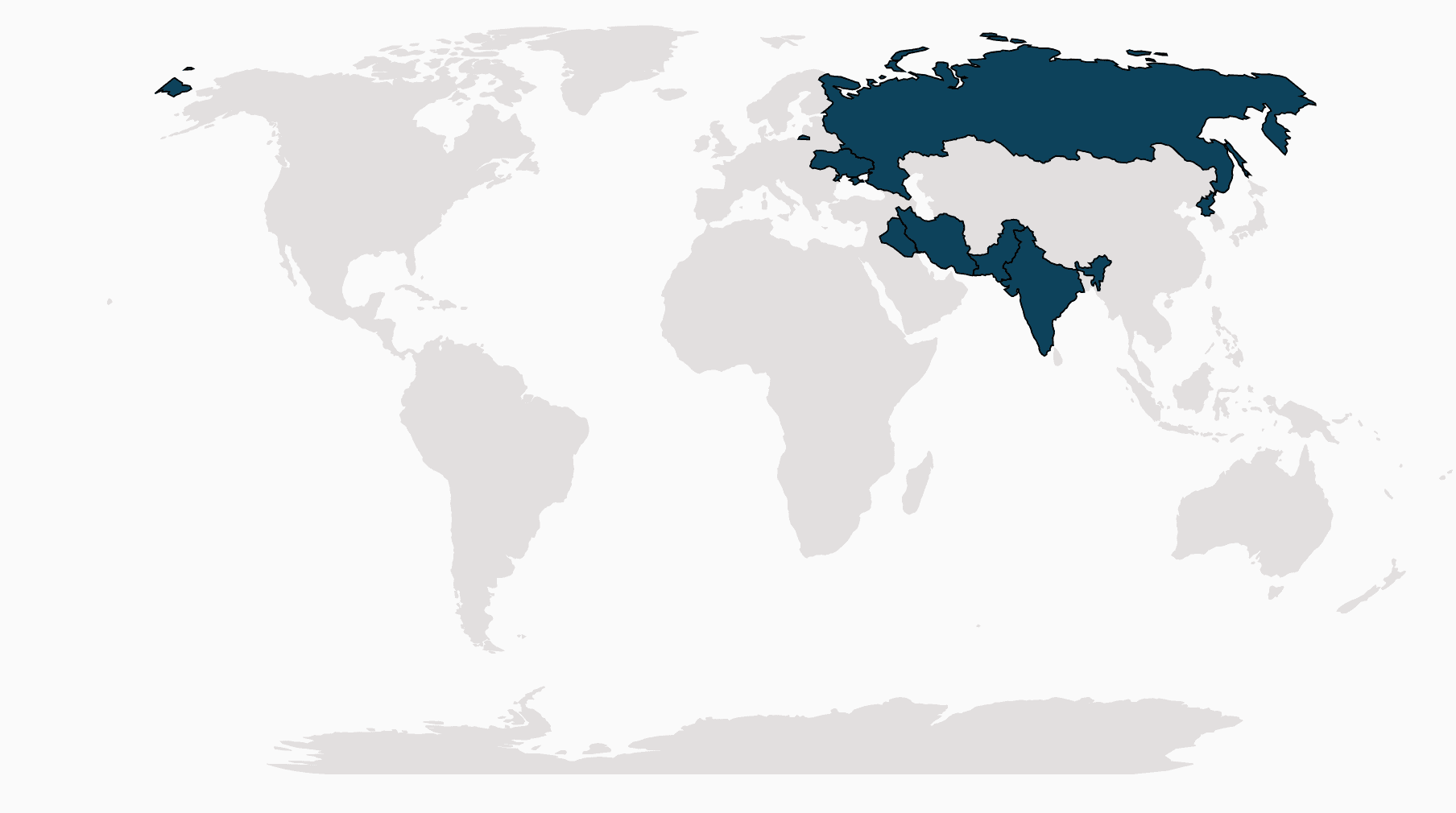

At their inception, most EU cooperation projects in the field of non-proliferation focused on the former Soviet Union and accompanied US-led Co-operative Threat Reduction (CTR) efforts.

Map showing Russia

Data: Natual Earth. Graphic: PRIF

However, the EU later shifted its geographical focus from the former Soviet Union to include regions such as North Africa, the Middle East and even Central and Southeast Asia.5 It also began to implement its projects independently from US efforts. Initially, these projects focused on the transfer of European standards in the area of export control of WMD-related materials and technologies.

The 2006 Instrument for Stability

The adoption of the Instrument for Stability in 2006 represented a breakthrough. By establishing non-proliferation as a priority, the EU was able to make resources available to implement ambitious outreach projects. This effort culminated in a new initiative to establish a network of Centres of Excellence aimed at the mitigation of risks associated with the chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) field. The initiative features a broad thematic focus encompassing any kind of CBRN risk. In cooperation with the UN Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute and the EU’s Joint Research Centre, it aimed at establishing small regional secretariats around the world to act as focal points for regional expertise on CBRN risks and their mitigation.

Countries with available uranium resources

Map showing member states of the EU Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Risk Mitigation Centres of Excellence (CoE)

Data: Natual Earth. Graphic: PRIF

In other words, the EU focused its efforts on capacity-building and knowledge transfer, two traditional strengths of its external action.

The funding of non-proliferation projects by other international bodies, such as the IAEA, the Preparatory Commission of the CTBT Organisation, or the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, notably increased.6

In the decade following the publication of the WMD Strategy, the EU spent over 70 million euros in support of most international non-proliferation agreements and institutions. Albeit unusual, the direct financial support of these international bodies by another international organisation – the EU7 – benefited from the existing capabilities in the partner organisations.

Examples for EU funding to international non-proliferation and disarmament bodies

IAEA

The European Council adopted a Decision on 19 February 2024 to support nuclear security activities of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) with 7.2 million Euro over 36 months. The funding will primarily:

- Build capacity in IAEA Member States and assist in strengthening nuclear security.

- Provide nuclear security assistance to Ukraine, including supporting the continued presence of IAEA staff at all nuclear sites in Ukraine.

- Strengthen women’s participation in nuclear security careers, particularly through the IAEA’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship Programme.

OPCW

Between 2021 and 2023, the EU supported the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) with 5.35 million Euros. The assistance aimed to:

- Verify the elimination of chemical weapons and production facilities.

- Prevent the re-emergence and reduce the risk of chemical weapons use.

- Ensure an effective and credible response to the use of chemical weapons.

CTBTO

The EU is one of the biggest financial contributors to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO). Between 2006 and 2022, the EU provided over 23 million Euro in support.

Activities funded by the EU ranged from regional workshops to encourage third countries to sign up to certain agreements to technical projects aimed at strengthening the capabilities of the Preparatory Commission of the CTBT Organization to detect nuclear weapon tests and the nuclear security work of the IAEA for the prevention of nuclear terrorism.8 The CFSP budget for non-proliferation and disarmament includes support for the development of epistemic communities conducting research in the field, notably via funding for the EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Consortium, convened by six leading European think tanks.

In sum, the adoption of the EU WMD Strategy led to a notable increase in EU activities in this area. In the long term, the largely successful implementation of European support projects strengthened the capabilities of international non-proliferation organisations such as the IAEA and CTBTO. However, most EU support remained technical in nature. Sensitive policies such as disarmament have been largely eschewed. The EU’s political influence on the non-proliferation regime has not increased, and the funding of projects implemented by other organisations limits EU visibility.9

Coordination at international fora

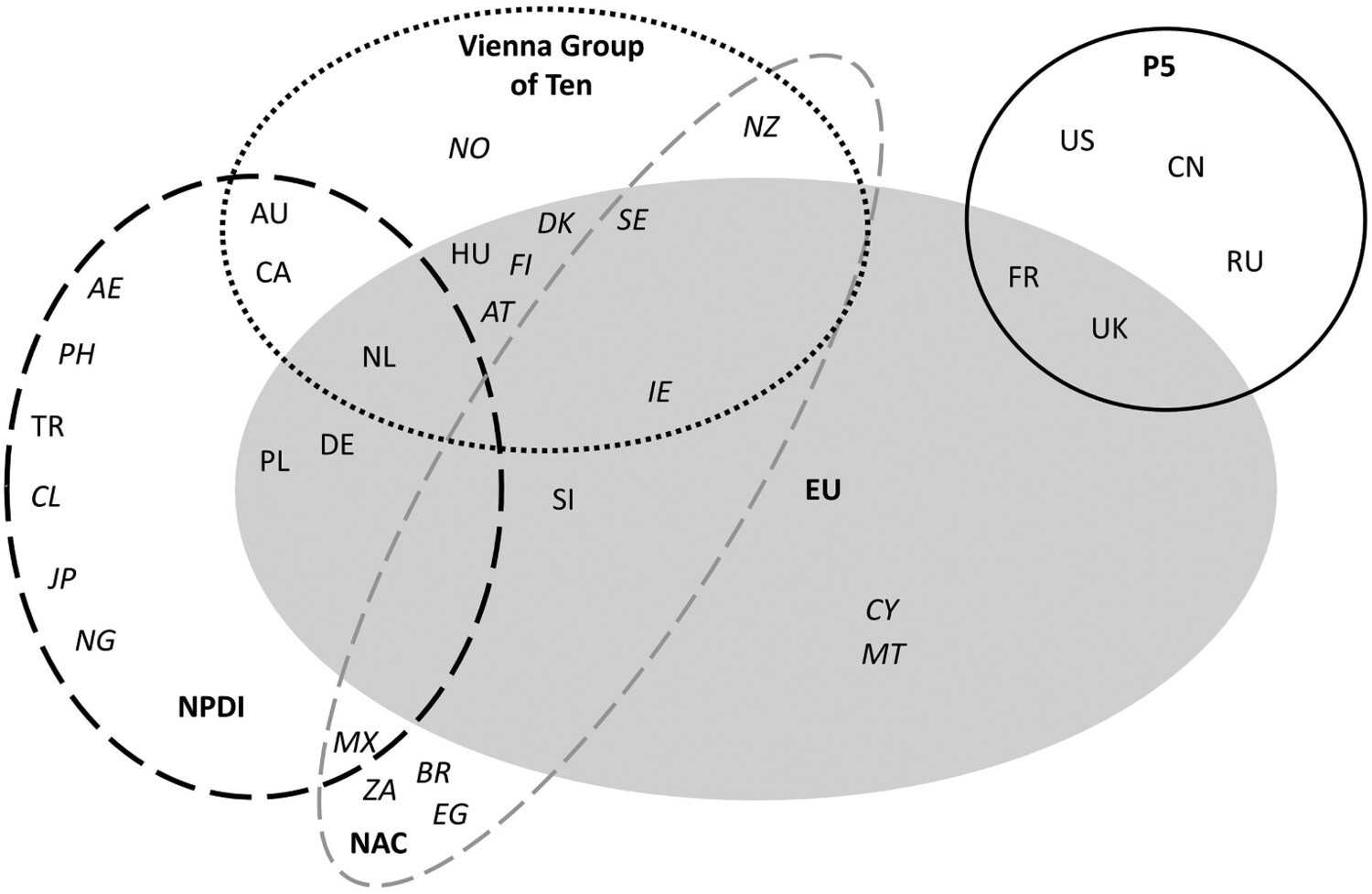

Member states began to coordinate their positions at NPT Review Conferences in the 1990s. At these conferences, the Presidency delivered statements on behalf of the EU and the EU submitted Working Papers with proposals that often proved subject to consensus, even among non-EU participants. At the same time, individual member states continued to present working papers either in their national capacity or as part of other groupings, such as France as a NWS or Ireland and Sweden as members of the New Agenda Coalition. The most celebrated example of EU action in non-proliferation was the diplomatic campaign for the indefinite extension of the NPT. Ahead of the conference, the EU agreed a Joint Action on the promotion of the indefinite extension among the parties. Through concerted diplomatic démarches, this goal was attained at the NPT Review and Extension Conference of 1995.10 After 1995, the EU adopted several instruments on multilateral fora. A Common Position featuring several objectives in the run up to the 2000 NPT Review Conference emphasised the promotion of multilateral treaty regimes as well as nuclear safety and export controls. Another Common Position aimed at the promotion of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was opened for signature in 1996 but its entry into force was conditional on it being signed and ratified by a list of over 40 states. Lastly, the EU adopted a Common Position on promoting the finalisation and universalisation of the Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation. The EU also launched a modest initiative to promote transparency in export controls, committing to contribute to the work of the NSG Working Group on Transparency. At the 2000 NPT Review Conference, the EU also backed an unsuccessful attempt to commend the Zangger Committee and national export control mechanisms for their role in halting proliferation (see LU12 for more details). Subsequently, member states tried to strengthen their national efforts in order to advance common goals in international non-proliferation institutions or international negotiations. This approach was consolidated as EU member states gradually joined virtually every international non-proliferation arrangement.11 In some of them, such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group or the Australia Group, they form the majority of members. Common statements or working papers by the EU in fora such as the IAEA General Assembly became a point of reference for third countries elsewhere.12

While CFSP coordination was successful, it did not increase convergence between member states when it came to their national positions on the issue. This is shown by an analysis of the convergence towards the EU position measured by member states voting behaviour at the Disarmament Committee of the UN General Assembly (UNGA). Over time, the positions of the member states only converged towards the EU stance to a minimal extent. The situation when it comes to EU convergence in this forum is most clearly characterised by the divergence of both NWS France and (at the time) the UK and disarmament-oriented member states such as Austria, Ireland or Sweden from the EU mainstream.13

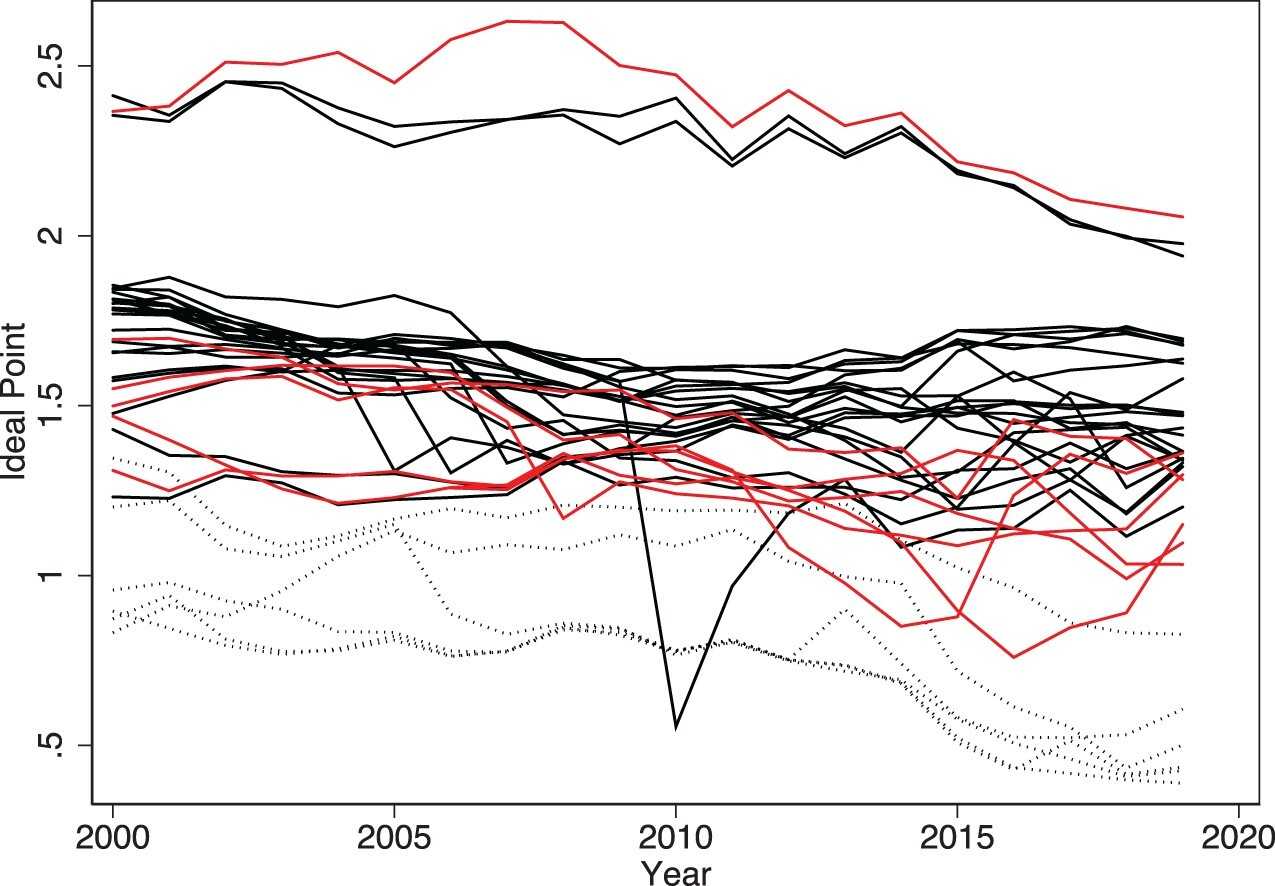

In focus: Evolution of convergence among member states on UNGA resolutions on nuclear weapons

In our 2023 article, “External drivers of EU differentiated cooperation: How change in the nuclear nonproliferation regime affects member states alignment” Michal Onderco and myself argue that changes in the global nuclear nonproliferation regime, particularly the rise of the Humanitarian Initiative (HI) and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), have led to differentiated cooperation among EU member states within the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Instead of a unified EU stance, two stable subgroups have emerged: one aligning with nuclear-armed states and NATO’s deterrence policies, and another advocating disarmament. This differentiation is driven by overlapping memberships in external nuclear governance groupings, demonstrating that external regime shifts, not just internal EU crises, shape CFSP alignment.

The figure above shows EU member states membership in select NPT groupings (as of 2015). Countries co-sponsoring the 2015 Joint Statement on the Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weapons are marked in italics.

The figure below illustrates patterns of convergence EU members over a period of two decades since the year 2000. The measurement of ideal points originates from the analysis of legislative behavior and permits to locate legislators’ stances on an axis, based on a large number of votes. The relative position of individual legislators on the axis is determined by their likelihood to vote similarly. The more likely two actors are to vote similarly, the closer they are to one another. By definition, ideal points are scale-free, and estimate a position of a country in a policy space on one particular dimension. In this test, the measurement of ideal points to voting by states instead of legislators, following Bailey et al. (2017), is applied. Ideal points are used because of their superior ability to discriminate between divisive and consensual resolutions, outperforming other measures of similarity of state preferences in UNGA.

The two nuclear powers in the EU are plotted on the top, together with the US as a non-EU NATO member. The six EU members outside NATO—i.e., Austria, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden—are visible in the dotted line below. Reviewing the figure, we observe that, twenty years ago, EU member states were divided into three major groups: European NWS, the thick mainstream composed of umbrella countries, and disarmament advocates. Over time, the European NWS moves closer to the rest of the EU. On the other hand, the non-NATO members of the EU move away from the EU mainstream. Interestingly, Finland is located halfway between the five EU members outside NATO listed above and the NATO countries, revealing that the country’s nuclear disarmament policy was distinct from the group of the five most proactive disarmament advocates.

Crisis-focused action

The non-proliferation efforts in key regions backed by the EU through nuclear-related assistance programmes range from support for the implementation of Russian disarmament commitments to participation in the Korean Energy Development Organisation (KEDO).14

The EU has responded with varying intensity to nuclear proliferation crises, i.e. situations where states initiated military nuclear programmes or aroused suspicions that they intended to do so. While the EU’s role in mitigating proliferation crises has a global scope, its response has traditionally been more substantial, in terms of financial allocation and level of engagement, when the crisis unfolded in European territory or in its proximity. The South Asian nuclear test elicited a weak response – just a joint condemnation and the postponement of an agreement – while the crises in Eastern Europe and the Near East sparked a great deal of activity (CTR activities and intense diplomatic action). The EU progressively became more cohesive over time, even though this process entailed the establishment of foreign policy coordination and representation formulas created ad hoc with no basis in the Treaty, notably the ‘E3 arrangement’. At the same time, the growing role of the EU in non-proliferation provided the HR with an opportunity to establish visibility for the role and acquire a genuine negotiation mandate in the run-up to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The management of proliferation crises has been coordinated with the US. Lack of agreement with Washington is perceived as problematic; indeed, the rift over Iraq was a sufficiently significant shock to give rise to the framing of the WMD Strategy. The EU increased its protagonism in the Iran file, and eventually parted from Washington’s line when it withdrew from the JCPOA. In addition to becoming more cohesive and resolute, EU responses to proliferation crises became increasingly coercive over time. Early episodes saw Brussels offering incentives and launching funding initiatives, while penalties were off the table. However, as the crises in the North Korea and Iran deepened, the EU proved willing to impose some of its most far-reaching sanctions to date in order to stem proliferation: an oil embargo and the disconnection of banks from the SWIFT network.15

The EU was involved in CTR efforts in Russia from an early stage. The concept of Co-operative Threat Reduction originated in the US Nunn-Lugar programme of 1991 designed to help successor states of the former Soviet Union to destroy WMD arsenals and establish verifiable safeguards. By assisting Russia to improve the safety of its nuclear material and abide by its disarmament commitments, the programme sought to prevent the diversion of these materials for illegal trafficking. The Union’s CTR activities in Russia were funded via the programme for Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Independent States (TACIS). The EU was one of the funding partners of the International Science and Technology Centre, a research institute set up to employ scientists who had worked in the Soviet WMD and missile programmes. The EU focused its CTR efforts in the fields in which the Community had competences and expertise, such as safeguards, nuclear safety and technological research, eschewing the military domain. CFSP instruments, especially Joint Actions, were adopted in order to allow projects with defence implications to be conducted, since these required a different legal basis.

The European Union’s responses to proliferation crises have traditionally been uneven. Some were barely dealt with at all, while others received substantial attention and resources, depending on the degree of agreement between EU members. The level of European engagement is largely a function of the geographic proximity of the proliferation crisis to the European continent. While Ukraine and Russia, and later Iran, received considerable attention, the EU’s reaction to the nuclear tests in South Asia was not as strong. The Union’s responses often supported action taken by the US, the principal actor in proliferation crises. Indeed, there is a tendency to follow, or complement, US responses to proliferation. The resolution of the Ukrainian crisis or the Iran nuclear file are examples of a coordinated ‘division of labour’, with the two actors proceeding in tandem to achieve shared objectives. Whenever member states disagreed on the adequacy of the US approach, the EU’s response was left wanting, as in Iraq. Interestingly, both in Ukraine and Iran, the EU offered increased contractual cooperation as an incentive to renounce nuclear weapons. This represented an attempt on the side of the EU to employ its trade and economic leverage to advance non-proliferation objectives, thus anticipating the subsequent introduction of political conditionality in this field with the non-proliferation clause.22

Footnotes

-

Álvarez-Verdugo 2006 ↩

-

Council of the EU 2003 ↩

-

Kienzle 2013 ↩

-

Grip 2009 ↩

-

Zwolski 2015 ↩

-

Anthony and Grip 2013 ↩

-

Dee 2023 ↩

-

Portela and Kienzle 2015 ↩

-

Portela and Kienzle 2015 ↩

-

Müller and Van Dassen 1997 ↩

-

Kienzle and Vestergaard 2013 ↩

-

Portela and Kienzle 2015 ↩

-

Onderco and Portela 2023 ↩

-

Portela 2015 ↩

-

Portela 2015 ↩

-

Müller and Van Dassen 1997 ↩

-

Portela and Jeantil 2024 ↩

-

Portela 2003 ↩

-

Müller 2011 ↩

-

Kienzle 2012 ↩

-

Kienzle 2013 ↩

-

Portela 2021 ↩