Nuclear sharing

During the Cold War, the United States placed several nuclear weapons inside the territory of allied NATO countries as a deterrent against a possible attack by Russia. The weapons were initially deployed in the United Kingdom, and later in Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Turkey and the Netherlands. This is referred to as ‘nuclear sharing’, or the ‘nuclear umbrella’, and is the basis of NATO’s common defence doctrine.

In the 1970s, the number of US weapons located in Europe peaked at approximately 7,000 units, which included mines, artillery, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and gravity bombs. The number later declined as a consequence of arms control agreements with the Soviet Union.1

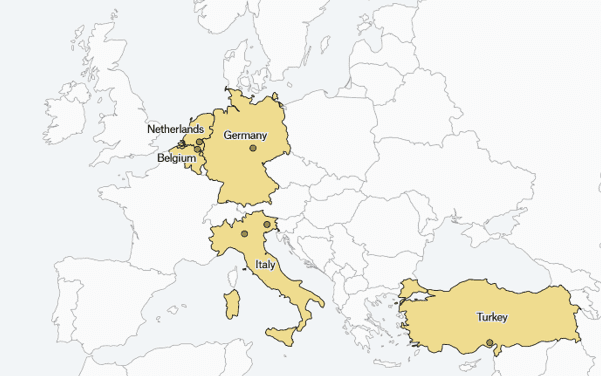

Today, US nuclear weapons remain in five NATO member countries, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Turkey and the Netherlands (see Learning Unit 11 for more details). These countries host approximately 100 NSNWs overall –specifically, B61 gravitational nuclear bombs.2 The US maintains complete control over the weapons it has deployed in Europe. According to NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements, if (and only if) the US decides to embark on a nuclear conflict, the control of these warheads would be transferred to its allies. Therefore, in time of war, Art. I and II of the NPT would not be observed.

Consequently, the concept of nuclear sharing could potentially be considered a violation of Art. I and II. Indeed, while there is an internationally recognised agreement on the US nuclear umbrella, it could be interpreted as a mechanism that goes against a basic obligation imposed by the NPT, namely not to transfer or receive nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices (or control over such weapons or explosive devices).

To understand this possible contradiction, it might be useful to consider two practical examples: Russia-Belarus and Pakistan-Saudi Arabia.

Russia-Belarus

In July 2022, approximately one year after Russia invaded Ukraine, Russian president Vladimir Putin announced his intention to deploy Russian NSNWs in Belarus.3 Such an arrangement would grant Moscow full control over any nuclear weapon deployed in Belarus in peace time, and this control would only be transferred to Minsk in the event of war. In any case, this would not change the status of Belarus as a non-nuclear weapon state but, and since Belarus is a signatory of the NPT, this could technically be seen as violating the treaty itself.4

Saudi Arabia-Pakistan

There have also been talks of a possible deployment of Pakistani nuclear weapons to Saudi Arabia.5 Unlike the Russia-Belarus case, where the former is a recognised nuclear weapon state (NWS), in this case neither of the countries are nuclear states. Moreover, while Saudi Arabia is a signatory of the NPT, Pakistan has never signed nor ratified the treaty. A potential deployment of Pakistani nuclear weapons to Saudi Arabia would therefore create an unprecedented situation: it would be an NPT violation on the part of Saudi Arabia, but not on the part of Pakistan.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

Between 2013 and 2016, the UN saw increased discussion on nuclear disarmament. This culminated, in January 2017, in the UN General Assembly’s decision to approve Resolution A/RES/71/2586 on ‘Taking forward multilateral nuclear disarmament negotiations’. In the First Committee vote of October 2017, a total of 123 states voted in favour, 38 voted against and 16 abstained. This mandated a ‘United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards their Total Elimination’, soon to be known as the ‘Ban Treaty’ conference, held between February and March 2017, and again between June and July of the same year.

Taking forward multilateral nuclear disarmament negotiationsA/RES/71/258

This resolution mandated a 'United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards their Total Elimination'

The conference on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) concluded in July 2017, with 122 votes in favour, 1 against (The Netherlands) and 1 abstention (Singapore). All the NWS, non-NPT states in possession of nuclear weapons and most states under the nuclear umbrella refused to attend the meeting, and made clear they were against it. The treaty opened for signature in September 2017 and entered into force in February 2021, after being ratified by 50 states. As of March 2023, the treaty has 92 signatories and 68 state parties. None of the NATO allies have signed the TPNW.

The main characteristics of the TPNW are the following:

- Comprehensive: it prohibits states from participating in any nuclear weapons activity (developing, testing, producing, acquiring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use, transferring, assisting, stationing)

- Non-discriminatory: it does not recognise the possession of any nuclear weapons as legitimate

- Wide in scope: it includes clauses for victim assistance and environmental remediation of nuclear use or testing

Those who claim the importance of joining the TPNW, often cite shortcomings of the NPT, such as the fact that the latter has effectively legitimised the possession of a nuclear arsenal for five countries, its weakness when it comes to convincing non-NPT countries to join the treaty and its overall vague commitment to disarmament.

However, the TPNW does not have a mechanism for the elimination of existing NWs – something that would have to be negotiated separately.

The process leading to the TPNW saw the active involvement of many civil society organisations, especially the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). In 2017, the Nobel Committee recognised the role of ICAN with the Nobel Peace Prize ‘for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons’.7

Withdrawal from the NPT

Article X.1 and the withdrawal procedure

In the context of the NPT, Article X.1 states that each country party to the treaty retains the right to withdraw from the treaty by exercising its own national sovereignty. Such withdrawal is permissible if a country determines that exceptional events, directly related to the subject matter covered by the treaty, have posed a significant threat to that country’s most vital interests. Should such a decision be made, the country intending to withdraw is obliged to notify all other states parties to the treaty, as well as the UN Security Council, at least three months prior to the entry into force of the intended withdrawal. This notification must also include a detailed account of the specific extraordinary events that the country considers to have jeopardised its essential national interests.8 The reason for involving the UNSC is that a withdrawal from the treaty can have significant negative implications for the international system as a whole. This notification process follows a similar model to other instruments of public international law, allowing the UNSC time to assess the legitimacy of the withdrawal and potentially take action under Chapter VII of the UN Charter.9

In terms of the substantive elements, the provision for withdrawal in the NPT includes the requirement of changed circumstances. This terminology, used in other international treaties, such as the ABM Treaty, the INF Treaty and the TPNW, allows a state to invoke changed circumstances as a justification for withdrawal. Again, the inclusion of this provision in the treaty is justified by the existence of similar provisions in other treaties and its recognition under the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, specifically Article 62 on change of circumstances and Article 60 on breach. Some legal scholars argue that failure to comply with the requirements outlined in Article X.1 does not invalidate a state’s decision to withdraw, as withdrawal remains a sovereign right. Therefore, the conditions listed in Article X.1 can be seen as a recommended procedure rather than a mandatory requirement for the recognition of withdrawal.10

Challenges and controversy over withdrawal rights

Article X.1 of the NPT is perceived as arbitrary, as the decision to withdraw is entirely at the discretion of states parties without requiring approval from any international organisation or judicial authority. This subjective nature of the withdrawal procedure has been criticised as a weakness of the treaty, as interpretations of what constitutes an exceptional event may vary. The only limitation on the state’s justification of withdrawal is the obligation to show good faith in treaty application, which is not clearly defined.11

During the negotiations of the treaty, no specific instructions were provide on the interpretation of Article X.1, thus allowing for flexibility. The negotiators wanted to ensure that withdrawal would be possible in certain situations, such as a non-state party acquiring nuclear weapons or the outbreak of war. The wording of the NPT allows for some creativity in determining the trigger event for withdrawal, as long as it is related to the purpose of the treaty, which is to prevent nuclear proliferation.12

Today the main concern is about Iran’s possible withdrawal from the NPT.13 Iran has previously threatened withdrawal, and its justification could be based on factors such as changes in its strategic environment14, including the US withdrawal from the JCPOA and the imposition of sanctions. As of today, the Iranian Parliament has tabled a bill to proceed with Iran’s withdrawal from the NPT as a result of recent military confrontations with Israel and the US bombing of its uranium enrichment plants in June 2025. There are also concerns about South Korea’s aim to acquire nuclear weapons in response to threats from North Korea. Some argue that South Korea’s withdrawal from the NPT would be legal and justified under Article X.1, given the specific circumstances it faces.15

Reforming Article X.1?

To date, efforts to regulate or reform the withdrawal provision of the NPT have been unsuccessful. Various proposals have been made, but they have not gained traction at the multilateral level. The US, for example, sought to address the deliberate abuse of the treaty without challenging or modifying Article X.1.16

The Vienna Group of Ten proposed that technologies acquired for peaceful purposes during a state’s participation in the NPT should remain under IAEA safeguards even after that state’s withdrawal.17 However, the 2020/2022 NPT RevCon Draft Final Document18 stated that it did not seek to limit or undermine the right to withdraw and emphasised that withdrawal does not modify prior obligations of certain states parties.

In any case, the withdrawal provision should be revised but not eliminated. Some reform proposals could include the establishment of a body to evaluate the justification presented by the withdrawing state, clear criteria for cases or scenarios justifying withdrawal and avoiding pre-emptive assessments. States in breach of their NPT obligations should not be allowed to withdraw or, if they do withdraw, their safeguards agreement with the IAEA should remain in force. Nuclear technology acquired during the state’s NPT membership should remain under international supervision to prevent its misuse for weapons purposes. Additionally, withdrawing states should not be allowed to retain nuclear technology acquired as NPT parties and they should continue to be held fully accountable for violations committed before withdrawal. The UN Security Council could discourage withdrawal by considering it a threat to international peace and security, imposing punitive measures in response.

Footnotes

-

https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/nuclear-weapons-europe-mapping-us-and-russian-deployments#:~:text=Current%20U.S.%20nuclear%20stockpiles%20are,the%20six%20facilities%20in%20Europe ↩

-

https://uploads.fas.org/2019/11/Brief2019_EuroNukes_CACNP_.pdf ↩

-

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-says-moscow-has-deal-with-belarus-station-nuclear-weapons-there-tass-2023-03-25/ ↩

-

https://thebulletin.org/2022/07/russia-belarus-nuclear-sharing-would-mirror-natos-and-worsen-europe-security/ ↩

-

https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/renewed-saudi-pakistan-contacts-revive-nuclear-fears ↩

-

https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N16/466/69/PDF/N1646669.pdf?OpenElement ↩

-

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2017/press-release/ ↩

-

https://www.un.org/en/conf/npt/2015/pdf/text%20of%20the%20treaty.pdf ↩

-

https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/8/issue/2/north-koreas-withdrawal-nuclear-nonproliferation-treaty ↩

-

http://www.qil-qdi.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Withdrawal_COPPEN_FINAL.pdf ↩

-

https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/16/will-iran-follow-north-korea-path-ditch-npt-nuclear-bomb/ ↩

-

https://www.nknews.org/2023/01/yoon-says-seoul-could-rapidly-acquire-nukes-if-north-korean-threats-increase/ ↩

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2013-07/news-briefs/us-pursues-penalty-renouncing-npt ↩

-

https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/revcon2022/documents/WP3.1.pdf ↩

-

https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/revcon2022/documents/CRP1.pdf ↩