The Non-Proliferation Treaty: An overview

Let us now go through the pillars in a little more detail.

Pillar 1: The NPT and nuclear non-proliferation

The precepts for the implementation of the principles of nuclear non-proliferation enshrined in the preamble to the treaty are elaborated in its first three articles.

In this regard, Article I refers to the commitments made by countries recognised as nuclear weapon states (NWS). These states undertake not to transfer nuclear weapons, nuclear explosive devices or control over them to any recipient, either directly or indirectly. They further agree not to provide any support, encouragement or inducement to non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS) to develop or acquire nuclear weapons or related devices.

In order for nuclear weapon states to adhere to Article I, they must establish comprehensive and effective measures to control the export of nuclear-related items. In addition, they must safeguard sensitive nuclear weapons-related information, facilities and materials.

Article II, on the other hand, concerns NNWS. Under this article, non-nuclear weapon states undertake to refrain from receiving transfers of nuclear weapons, nuclear explosive devices or control over them, either directly or indirectly. They also undertake not to engage in the production or acquisition of nuclear weapons or related explosive devices, and not to seek or accept assistance for the development of nuclear weapons or similar devices.

Taken together, Articles I and II are primarily aimed at preventing the proliferation and spread of nuclear weapons, along with their associated technologies, as well as curbing the expansion of existing nuclear arsenals.

Finally, Article III focuses on NNWS again, outlining their obligations regarding the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). These states commit to submit to the IAEA safeguards to ensure that their nuclear activities are exclusively for peaceful purposes. As part of this commitment, NNWS must agree arrangements with the IAEA to apply safeguards to all nuclear material used in peaceful nuclear activities. These arrangements are to be initiated immediately upon the state’s accession to the treaty and are to enter into force within 18 months.

In essence, Article III reinforces the importance of ensuring the peaceful nature of nuclear activities in non-nuclear weapon states through IAEA monitoring and verification.

Pillar 2: The NPT and nuclear disarmament

The disarmament pillar of the NPT is elaborated in Article VI, which obligates all parties to pursue negotiations aimed at implementing measures concerning three ambitious goals: ending the nuclear arms race, achieving nuclear disarmament, and drafting a treaty for general and complete disarmament.2

Through Article VI, NPT members elaborated the concept of the so-called ‘Grand Bargain’: in exchange for NNWS giving up any potential ambition to pursue nuclear weapons, NWS commit to pursuing nuclear disarmament. The Grand Bargain could be defined as the compromise that made the NPT possible; it is the basis on which the treaty was built.

However, discontent over the pace of disarmament has existed throughout the NPT’s history. The Cold War made disarmament impractical. Once it ended, frustrations only increased: NNWS felt the disarmament obligation was being disregarded, whilst the NWS maintained they had done much to fulfil their commitment, as the number of US and Russian nuclear weapons had decreased from a peak of over 60,000 in the mid-1980s to approximately 8,000 in 2020.3 The continued failure to achieve nuclear disarmament is causing tensions among the parties involved in the Grand Bargain.

In 1994, the Secretary-General of the United Nations announced a decision taken by the General Assembly to put the following question to the International Court of Justice (ICJ): ‘Is the threat or use of nuclear weapons in any circumstance permitted under international law?’. Though the ICJ was not able to reach a definitive conclusion as to the legality or illegality of the use of nuclear weapons, it did conclude that ‘there exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control’.

Disarmament approaches

| Step-by-step | Comprehensive |

|---|---|

| - Favoured by NWS, which claim they have done much to comply with Art. VI, as they have reduced the number and types warheads in their nuclear arsenals, as well as stopped nuclear testing. - Also favoured by some NNWS. - Stability as a prerequisite for disarmament. - Series of steps towards complete disarmament (CTBT, FMCT, etc.). | - Favoured by the majority of NNWS, which argue that nuclear arsenals of NWS are bigger than necessary, that NWS are not putting sufficient effort into conducting good faith negotiations towards disarmament and that they are continuing to conduct other dangerous practices (e.g. modernisation, deployment, targeting).- Supports the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). - Disarmament is considered the basis for stability and security. |

In an effort to strengthen nuclear disarmament, starting at a regional level, Article VII of the NPT establishes nuclear-weapon-free zones (NWFZs): regions characterised by the total absence of nuclear weapons, enforced by an international system of verification and control administered by the IAEA (for more details on the issue see LU06).4

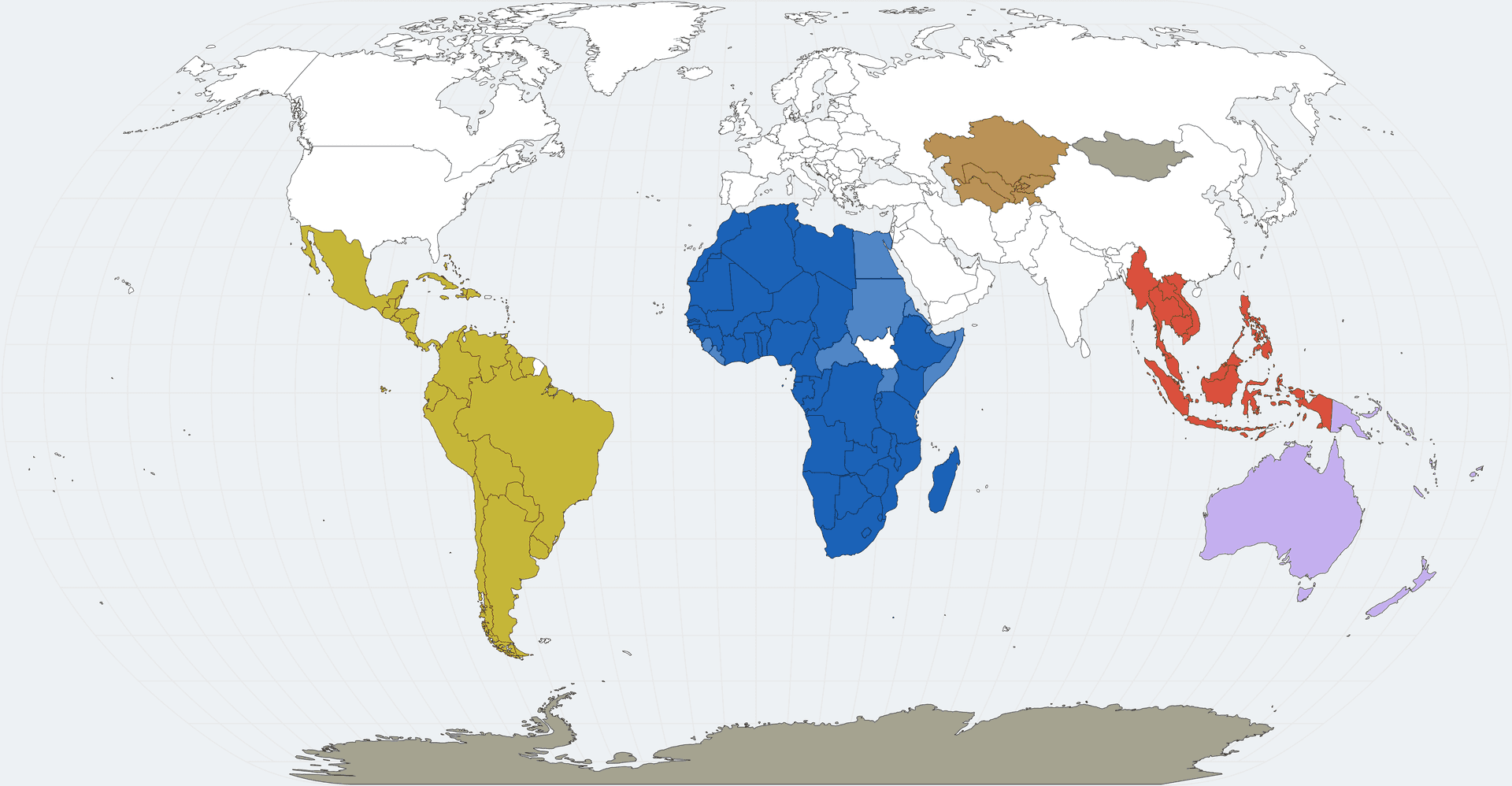

Today, there are five NWFZs worldwide:

- Latin America (Treaty of Tlatelolco, 1967)

- South Pacific (Treaty of Rarotonga, 1985)

- Southeast Asia (Treaty of Bangkok, 1995)

- Africa (Treaty of Pelindaba, 1996)

- Central Asia (Treaty of Semipalatinsk, 2006)

Two additions should be made to this list. In 1961, the Antarctic Treaty entered into force. Among other things, the treaty prohibits nuclear explosions, radioactive waste disposal and military deployments in the Antarctic Treaty Area (ATA). Moreover, in 1992, Mongolia declared its territory a a nuclear-weapon-free zone. This status was formally recognised with the General Assembly resolution 53/77 D, entitled ‘Mongolia’s international security and nuclear-weapon-free status’.5

Treaties establishing NWFZs can be seen as successful experiments in regional disarmament. They include a legally binding protocol signed and ratified by the nuclear-armed states, which commit to respect the status of these regions and to abide by a defined set of security assurances. Today, NWFZs cover most of the world.

| Treaty | Protocol | Signed | Ratified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tlatelolco6 | I | FR, NL, UK, US | FR, NL, UK, US |

| II | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | |

| Rarotonga7 | I | FR, UK, US | FR, UK |

| II | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | CHN, FR, RU, UK | |

| III | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | CHN, FR, RU, UK | |

| Bangkok8 | I | \ | \ |

| Pelindaba9 | I | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | CHN, FR, RU, UK |

| II | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | CHN, FR, RU, UK | |

| III | FR | FR | |

| Semipalatinsk10 | I | CHN, FR, RU, UK, US | CHN, FR, RU, UK |

Since the 1970s, there have been discussions about a regional agreement to eliminate nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Beginning in 2019, there have been three sessions of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction. During the third and latest session, which was held in November 2022, members exchanged views on issues including their core obligations and their membership in other relevant multilateral legal instruments related to weapons of mass destruction.11

Pillar 3: The NPT and the peaceful uses of nuclear energy

The principle and rules for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy are set out in Article IV of the NPT. This article states that ‘Nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of all the Parties to the Treaty to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination and in conformity with Articles I and II of this Treaty’12.

This first paragraph of Article IV recognises the inherent right of all parties to the treaty to engage in research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. Importantly, this right is conditional on compliance with the principles set out in Articles I, II and III, relating to the proliferation and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

The article continues by bestowing on all signatory nations a responsibility to promote and enable a robust exchange of various resources, including equipment, materials and knowledge related to science and technology. This exchange is aimed primarily at the peaceful use of nuclear energy. In essence, these countries commit to facilitating the exchange of tools, substances and information that can be used constructively in nuclear-related efforts.

In particular, countries that have the capacity to do so are encouraged to collaborate in a variety of ways. This collaboration may involve working independently or partnering with other countries or international organisations. The main objective of such collaboration is to foster the development of beneficial applications of nuclear energy. This collaborative effort is especially important in regions where countries have chosen not to possess nuclear weapons and also participate in the treaty. These regions are often characterised by limited access to advanced technologies and resources.

In this collaborative effort, it is crucial that participating nations take into account the unique needs and circumstances of less developed regions around the world. These considerations should guide the way in which resources are shared and initiatives are pursued, with the goal of promoting balanced and equitable progress in the peaceful applications of nuclear energy.

Different interpretations of Article IV have emerged. Some countries claim that it guarantees an unconditional right to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. Others argue that this right is dependent on compliance with non-proliferation requirements. Non-compliance with these requirements could lead to limitations on access to nuclear materials and technology.

These different interpretations extend to the scope of nuclear technology sharing.13 The term ‘the fullest possible’, in the second paragraph of Article IV, has generated different perspectives. Some advocate a narrow view, suggesting that nuclear cooperation should have limitations and may not require the sharing of specific materials or technology. In contrast, a broader interpretation posits that the parties to the treaty are obliged to actively engage in nuclear cooperation without strict restrictions other than those set out in Articles I and II.14

This variation in interpretation has given rise to conflicting views among the parties to the treaty on the scope and implementation of Article IV. The challenge arises from the objective of safeguarding the right to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, while preventing its misappropriation by states seeking to develop nuclear weapons capabilities. Moreover, there is no consensus on how to assess compliance with Article IV, as there are no standardised criteria for assessing the fulfilment of obligations related to the exchange of equipment, materials and information.

Footnotes

-

https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/240/63/PDF/NR024063.pdf?OpenElement ↩

-

https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/001/85/IMG/NR000185.pdf?OpenElement ↩

-

https://www.un.org/nwfz/content/mongolias-nuclear-weapon-free-status; https://www.un.org/nwfz/content/mongolias-nuclear-weapon-free-status; https://daccess-ods.un.org/tmp/7465639.11437988.html; https://www.nti.org/education-center/treaties-and-regimes/antarctic-treaty/ ↩

-

https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/705/49/PDF/N2270549.pdf?OpenElement ↩

-

Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. art IV.I & II. 1968. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/conf/npt/2015/pdf/text%20of%20the%20treaty.pdf ↩

-

https://npolicy.org/article_file/Nuclear_Technology_Rights_and_Wrongs-The_NPT_Article_IV_and_Nonproliferation.pdf ↩