Why history is important

The beginning of the nuclear era

In 1933, Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard was the first to conceive the notion that uranium atoms could split and produce a nuclear chain reaction, opening the possibility of developing a nuclear explosive device.

However, the idea that it was possible to manufacture such a weapon was dismissed because of the amount of uranium needed to start the chain reaction. It was not until Otto Frisch and Rudolph Peierls suggested that uranium-235, a fissile isotope of uranium, could be extracted from uranium ore, and that this would be able to sustain the chain reaction, that the notion of such a device was taken seriously.

The Frisch-Peierls Memorandum persuaded the British government to fund a bomb project led by the MAUD committee. The British, however, came to the conclusion that they could not bear the financial cost of the research and development of the atomic bomb, and over the course of 1941, sent most of their research outputs to the US. This led to the creation, in 1942, of the Uranium Committee, set up to study the possibilities of developing such a weapon.1

By the spring of 1945, the work of the Uranium Committee had led to the notorious ‘Manhattan Project’ and in 1945, scientists and engineers were ready to begin assembling the bomb which, by the end of May 1945, led to a demonstration explosion against Japan being proposed in order to bring about an early end to the war.2 At the same time, on 16 July 1945, at 5.30 a.m, the first successful test of an atomic bomb took place at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

In the summer 1945, the US, UK and China sent an ultimatum to Japan calling on them to surrender unconditionally or face ‘immediate and complete destruction3’. Japan’s failure to respond sealed the fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: On 6 August 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and on 9 August, the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Japan surrendered unconditionally on 14 August 1945. The nuclear weapon had entered the battlefield.

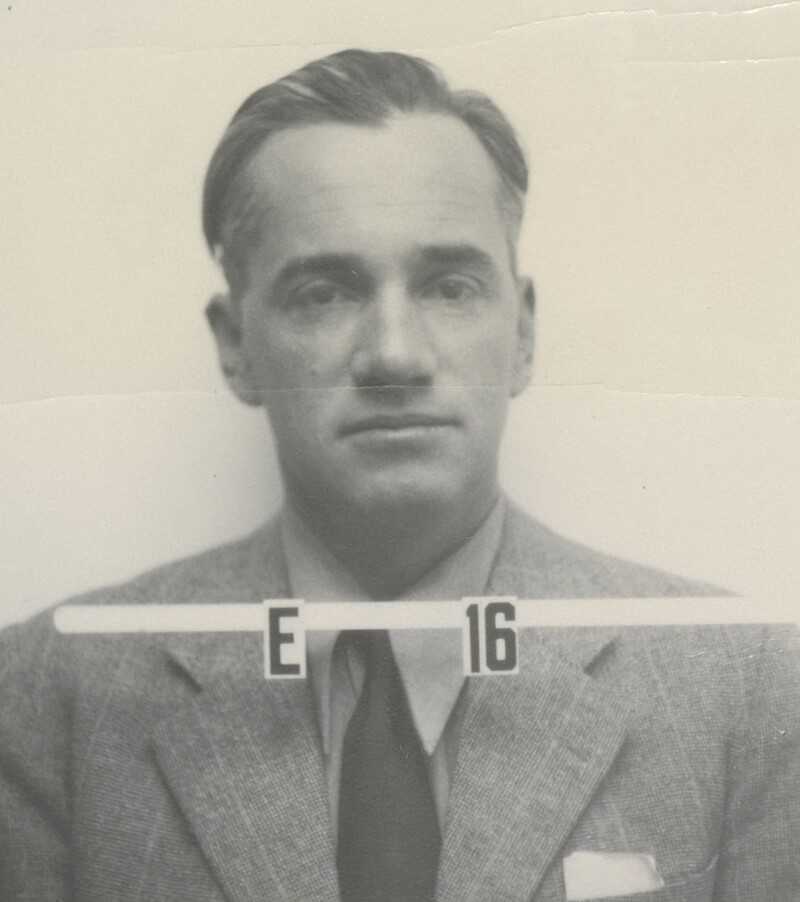

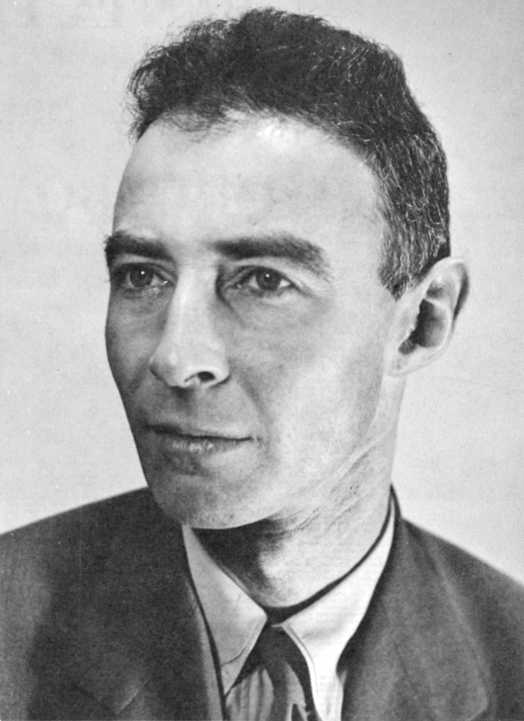

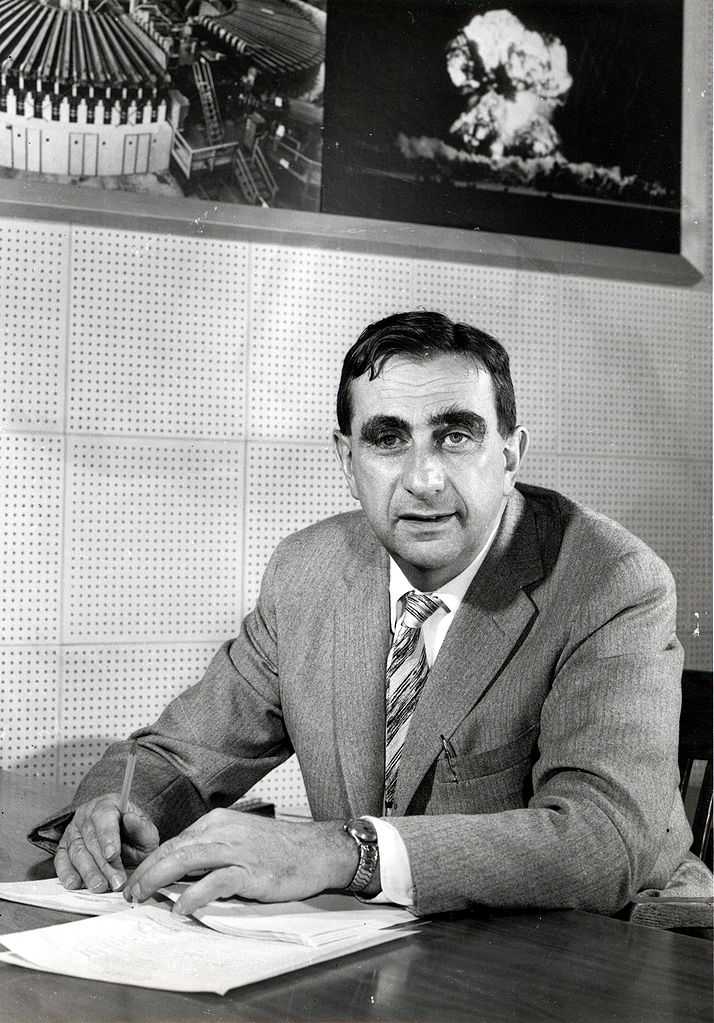

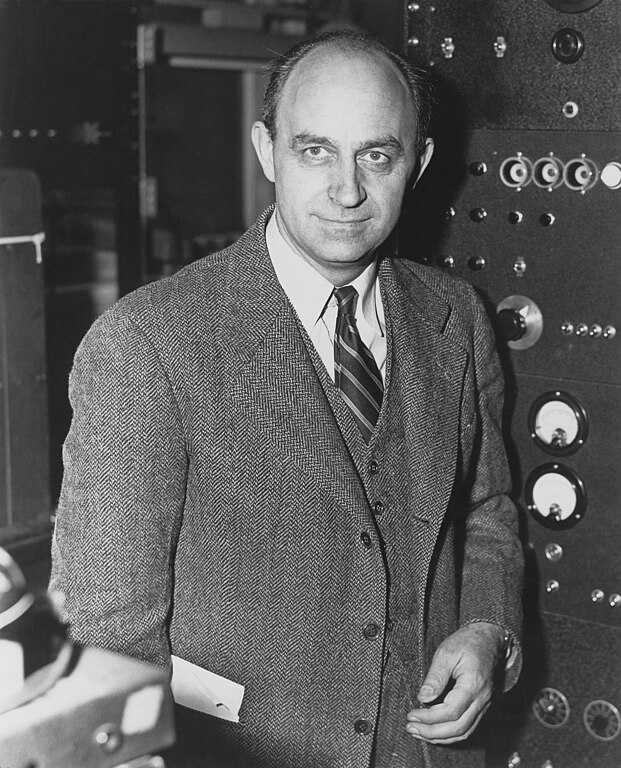

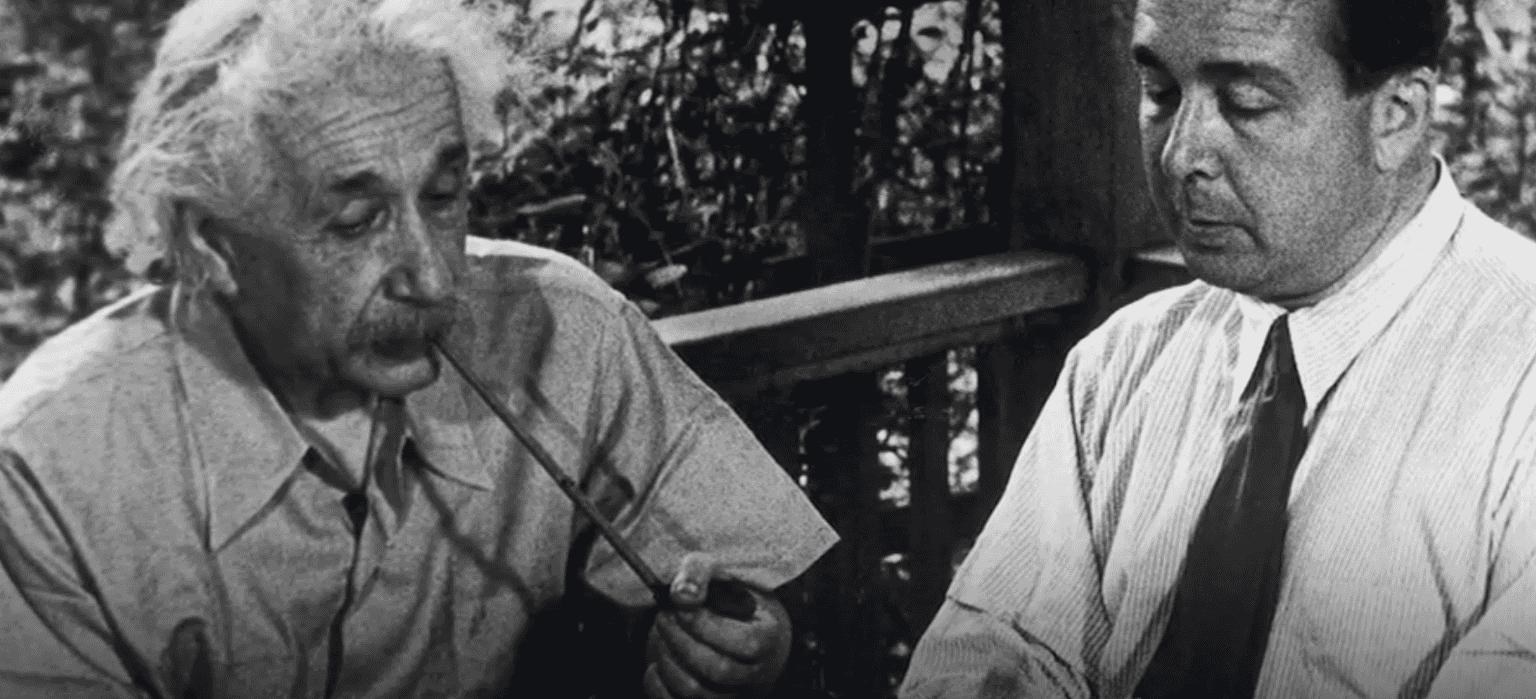

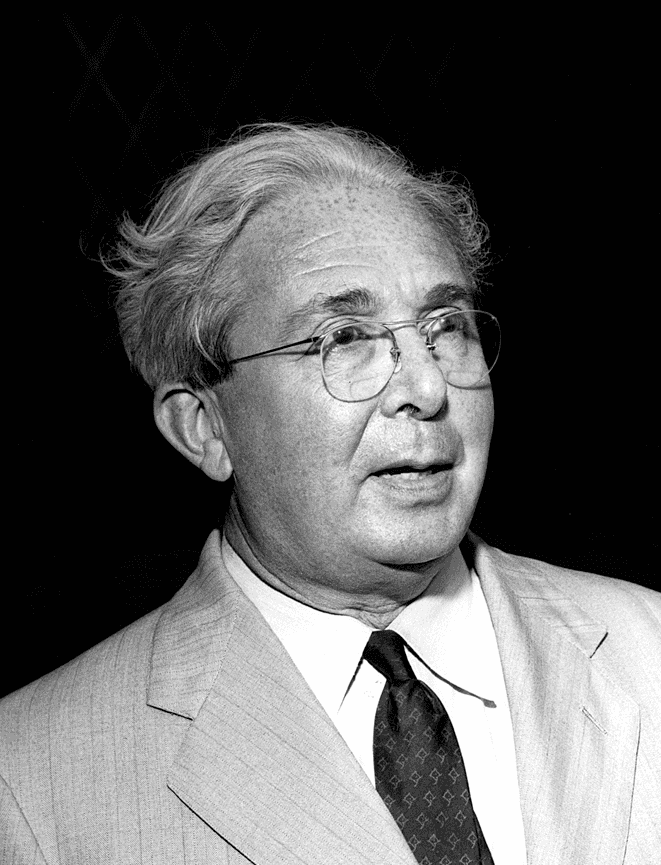

(Some) important scientists who contributed to the development of the atomic bomb

Leó Szilárd (Budapest, 11 February 1898 - La Jolla, California, 30 May 1964) was a Hungarian-American Jewish physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project. He is also known as the author of the letter (also signed by Albert Einstein) to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt in August 1939 that led to the development of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

The first international efforts to ban nuclear weapons

The sheer destruction caused by the new nuclear weapons hit many people hard. It is therefore not surprising that at the first meeting of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) on 24 January 1946, the first resolution adopted was to establish an Atomic Energy Commission, charged among other things with submitting proposals for ‘the elimination of atomic weapons from national armaments’4. The resolution was adopted unanimously by all 51 member states.

ESTABLISHMENT 0F A COMMISSION TO DEAL WITH THE PROBLEMS RAISED BY THE DISCOVERY 0F ATOMIC ENERGYA/RES/1(I)

This resolution mandated an Atomic Energy Commission, charged among other things with submitting proposals for 'the elimination of atomic weapons from national armaments'

The US government, meanwhile, had anticipated these developments by establishing an advisory commission under the chairmanship of David Lilienthal to consider proposals for the establishment of a United Nations commission to control the international development of atomic energy. Bernard Baruch was appointed to present the proposal to the United Nations.5

On 14 June 1946, Baruch presented the proposal to the UN General Assembly (UNGA). It called for a ban on the manufacture of atomic bombs and for all phases of the development and use of atomic energy to be placed under international authority. Compliance would be ensured through verification processes. However, until a treaty to this effect was approved by the United Nations and entered into force, the United States was to continue to have a monopoly on atomic secrets and would not commit to ending the production of new atomic weapons until there were effective and secure controls, including on-site verification on Soviet territory.

Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko rejected the US proposals and on 19 June 1946, presented an alternative proposal that would see all parties commit to not using atomic weapons; prohibit the production or maintenance of such weaponry; and required the destruction of all existing weapons within three months of the treaty’s adoption.

However, the Soviet Union offered no means of verification in support of its proposals, making them unacceptable to the United States.6

The failure of negotiations in June of that year ended the first attempt to eliminate atomic weapons, and by the mid-1950s, US and Soviet leaders had rejected the idea of banning them and instead sought ways to control them, thereby strengthening deterrence with a view to reducing the risk of nuclear war.7

The Irish resolution

On 17 October 1958, a significant event took place that years later would directly influence the negotiation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Ireland submitted to the UNGA the first draft resolution highlighting the dangers posed by the increase in the number of states in possession of nuclear weapons. The proposal called for the formation of an ad hoc committee to study these dangers and for all states to suspend nuclear testing, nuclear powers not to supply nuclear weapons to other states, and non-nuclear states to cease any efforts to develop nuclear weapons. However, this initial proposal did not find sufficient support and had to be withdrawn.8

A year later, in 1959, Ireland sent its proposal back to the Ten Nations Committee on Disarmament, established to address the issue of nuclear disarmament during the Cold War, suggesting that the adoption of an international agreement subject to controls and inspections could be an effective mechanism for controlling nuclear proliferation.9 On this occasion, the US responded favourably, considering the proposal to be consistent with the objectives of nuclear non-proliferation and nuclear cooperation with other states. However, the Soviet Union rejected it on the grounds that it did not exclude the possibility of installing nuclear weapons outside the territory of the nuclear weapon states themselves.10

In 1960, a second text submitted by Ireland went further than the initial proposal of 1958, as it made it clear that the aim of the resolution was the adoption of a permanent non-proliferation agreement and therefore required non-nuclear states to commit not to acquiring nuclear weapons.11 It also required the nuclear weapon states to cease transferring nuclear technology, as well as information relevant to the manufacture of nuclear weapons to non-nuclear states.

This proposal was approved by the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries, enabling its final approval by the UNGA on 4 December 1961, with the United States and other NATO allies abstaining. The resolution represented the first step towards the negotiation of a comprehensive Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The Eighteen Nation Committee and the negotiation of the NPT

The attempt to place all nuclear activities of states under the control of an international organisation was too ambitious and difficult to implement because of opposition from the major nuclear powers, and had to be replaced by negotiations to achieve individual elements of such a strategy. The first element of these negotiations was the adoption of a nuclear non-dissemination treaty, based on the proposals contained in the Irish resolution of 1958. Negotiations for the adoption of a Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty started in spring of 1965 in the Eighteen Nation Committee.

The negotiation process was divided into two phases. In the first phase, the two major powers (the US and the Soviet Union) discussed possible ways forward for the NPT negotiations. The second phase involved multilateral discussions aimed at formulating the specific clauses to be contained in the treaty.12

Despite the difficulties, a set of proposals and provisions to prohibit the transfer of nuclear weapons to non-nuclear countries were drafted. The final decision was taken during the 20th session of the UN General Assembly with the adoption of Resolution 2028 (XX)13. The Resolution contained five basic principles which would go on to form the basis of a subsequent Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. These principles were:

- To prevent loopholes that could allow nuclear or non-nuclear states to proliferate nuclear weapons, either directly or indirectly, in any form.

- To establish an acceptable balance of mutual responsibilities and obligations between nuclear and non-nuclear states.

- To open the path towards general and complete disarmament.

- To include acceptable and directly applicable provisions to ensure its effectiveness.

- To guarantee the right of any group of states to conclude regional treaties with a view to securing the total absence of nuclear weapons in their respective territories.

After several amendments, the United States and the Soviet Union jointly submitted the draft final text of the NPT to the Eighteen Nation Committee on 14 March 1968. The United Nations General Assembly adopted the treaty by Resolution 2373 on 12 June 1968.

Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), updated weekly

Data: [United Nations Treaty Collection] (https://treaties.un.org/pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=08000002801d56c5), Natual Earth. Graphic: PRIF

From Theory to Treaty: The Path to Nuclear Weapons and Non-Proliferation (1933–1968)

- 1933

First theoretical conceptualisation of nuclear fission by Leo Szilard

- 1940

Frisch-Peierls Memorandum convincing the British Government to fund a bomb project

- 1942

Creation of the British Uranium Committee which leads to the British/US ‘Manhattan Project’

- 1945

July 16: first successful test of an atomic bomb at Alamogordo, New Mexico, USA

- 1945

August 6: Nuclear bombing of Hiroshima, Japan

- 1945

August 9: Nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, Japan

- 1945

August 14: Unconditional surrender of Japan

- 1946

First debates within the United Nations, leading to the establishment of the Atomic Energy Commission

- 1946

US Baruch plan to establish international control over nuclear energy, rejected by the Soviet Union. Soviet counter-proposal rejected due to insufficient verification

- 1958

Irish resolution to UN: calling for preventing the spread of nuclear weapons, laying groundwork for future non-proliferation efforts

- 1960

Second Irish proposal

- 1961

Second Irish proposal approved by Soviet Union/Eastern Bloc, USA and other NATO allies abstaining. First step towards NPT

- 1968

June 12: Adoption of the NPT through UN-Resolution 2373

Footnotes

-

Greville Rumble. The Politics of Nuclear Defence: A Comprehensive Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1985. ↩

-

Martin J. Sherwin A World Destroyed: The Atomic Bomb and the Grand Alliance. New York: Vintage, 1977. p. 302. ↩

-

Greville Rumble. The Politics of Nuclear Defence: A Comprehensive Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1985, p.27. ↩

-

United Nations General Assembly. Establishment of a Commission to Deal with the Problems Raised by the Discovery of Atomic Energy 1946, p.9 ↩

-

David Fischer. History of the International Atomic Energy Agency: The First Forty Years. Vienna: IAEA, 1997. ↩

-

Holloway, David J. “The Soviet Union and the Baruch Plan | Wilson Center.” www.wilsoncenter.org, 2020. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/soviet-union-and-baruch-plan ↩

-

Nina Tannenwald. “Stigmatizing the Bomb: Origins of the Nuclear Taboo.” International Security 29, no. 4 (April 2005): 5–49. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2005.29.4.5 ↩

-

Chossudovsky, Evgeny M. “The Origins of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Ireland’s Initiative in the United Nations (1958-61).” Irish Studies in International Affairs 3, no. 2 (1990): 111–35 ↩

-

Darryl Howlett and John Simpson. The Future of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995. ↩

-

James Stocker. “Accepting Regional Zero: Nuclear Weapon Free Zones, U.S. Nonproliferation Policy and Global Security, 1957–1968.” Journal of Cold War Studies 17, no. 2 (April 2015): 36–72. https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00547 ↩

-

Chossudovsky, Evgeny M. “The Origins of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Ireland’s Initiative in the United Nations (1958-61).” Irish Studies in International Affairs 3, no. 2 (1990): 111–35. ↩

-

Darryl Howlett and John Simpson. The Future of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995., p.21. ↩

-

United Nations General Assembly Resolution Adopted by The General Assembly During Its Twentieth Session on The Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. A/Res/2028(XX). 1965. pp.7-8. ↩